Catalog Number: CG-0043

The genus Solenochilus was first described by Meek & Worthen in 1870.

Found next to a burn pile, the piece of limestone this specimen belonged to was cooked at high heat for a length of time. The pit was used to burn occasional garbage. A number of pieces of Brush Creek Limestone were used to ring the pit, and several were cracked and eroded from the hear. The back portion of the shell steinkern has melted plastic on it.

A benefit of the heat, however, was it’s effect on the rock. The rock was easily split and the Solenochilus was mostly in-tact. The red band was likely due to the burning that occurred in close vicinity to the specimen. The original shell material did stick to the opposite piece of rock it detached from.

The identification as Solenocheilus has been verified by Dr. Royal Mapes. It has the correct shape and size. He suspects it is a juvenile which accounts for the slight differences in shell morphology. The portion of the shell that tucks under is very similar to the first example I found in 2019. The only thing that casts doubt is the maximum width of the body chamber. This specimen is very similar in overall size as my first, but it does not get as wide and flat. However this could be due to flattening before or after the fossilization process in the first specimen.

Bite Marks?

As with my last Solenochilus, I reached out to Dr. Mapes for assurance of identification. One detail that I missed but Dr. Mapes picked up on was the puncture marks near the aperture. He said they are probable bite marks. Dr. Mapes and H.C. Hansen wrote a paper in Lethaia about Pennsylvanian shark-cephalopod predation. Their conclusion was an attack by Symmorium reniforme, which has teeth to make such a puncture. The age range of the genus Symmorium is from 376.1 to 306.95 million years ago. They are known from Illinois but I can not find specimens from Western Pennsylvania.

Another consideration is predatory gastropods. However I am told that these typically produce a single puncture and of varying sizes. They would not likely be three holes of nearly the exact same size equally spaced out on the same plane. Also, cephalopods tend to be fast active swimmers. This would further reduce the likelihood of a snail being able to latch on and bore a hole.

Specimen when first found and wet.

The following photos show the specimen just minutes after finding it. It was still attached to some rock matrix. I quickly grabbed my air scribe and cleaned away additional matrix.

Photos of specimen using flash.

Photos of the specimen using a Nikon camera with flash. While cell phone photos of late are exceptional, there is not yet a substitute to a camera with a larger sensor and a good flash. The specimen was laid on a piece of white paper and the flash was aimed at the ceiling. Photos were adjusted as RAW with the white values increased until they were blown out around the specimen.

Compared to CG-0025 Solenochilus

The first Solenochilus is wider at the end of it’s body chamber than this specimen. Mapes said this newer specimen is likely a juvenile, which accounts for the small morphometric differences. The point where the shell tucks under, which is present on both shells, is very similar in both. The first specimen did not show suture lines as well as this one does.

Solenochilus vs Solenocheilus

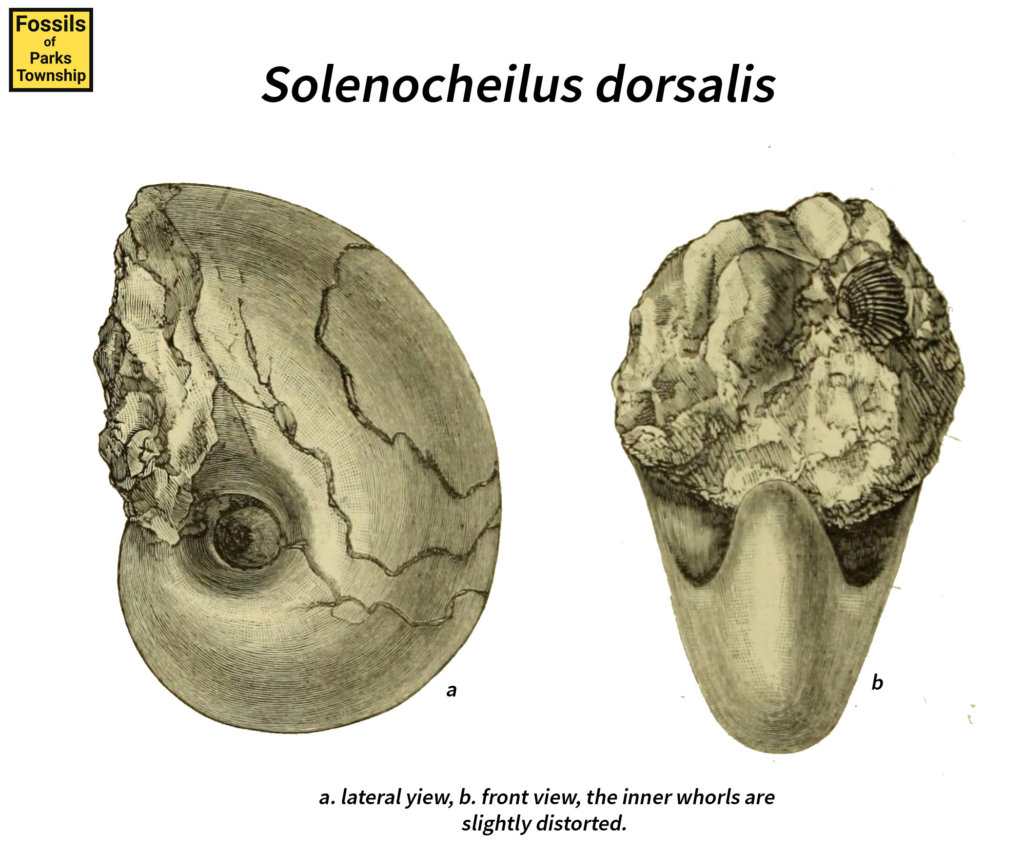

Online I have come across two spellings of Solenochilus. The older spelling appears to add an extra e before the “ilus” portion of the name. This can be slightly confusing for research as the older spelling returns less results. An example of a specimen using the old spelling is shown below.

The First Solenochilus Specimen

More about Solenochilus online

- Taxon Page – Fossilworks

- Specimen Page with Photos – GB3D Type Fossils

More Information and Research

- Royal Mapes Collection – American Museum of Natural History

- Kelley, Patricia & Kowalewski, Michał & Hansen, Thor. (2003). Predator—Prey Interactions in the Fossil Record. 10.1007/978-1-4615-0161-9.

- Mapes, Royal H. & Hansen. Michael C. 1984 07 15: Pennsylvanian shark-cephalopod predation: a case study. Lethaia, Vol. 17, pp. 175-183. Oslo. ISSN 0024-1164.