The Glenshaw Formation’s local section is home to many different phyla or classes of Marine and Plant fossil fauna. This formation is late Pennsylvanian in age. The types are not equally represented in each area. Rocks from one hillside may be diverse, whereas rocks from the opposite hillside may have only a few species. Consistancy varies throughout the formation, where some areas have no detectable fossils.

The visible fauna is from two significant kingdoms of life, Animalia and Plantae. There are likely examples of Fungi, and perhaps Protozoa and Bacteria, but I do not have the knowledge to find and identify these types. Animalia is grouped into two main types, vertebrates and invertebrates. This is not something always written in scientific classification. Meanwhile, it is widely known which type belongs to which. For example, Petalodus belongs to the subphylum Vertebrata.

Kingdoms

Over the last 287 years since Linnaeus (1735) first set two kingdoms, Vegetabilia and Animalia, there have been many revisions to the distinction. Haechel replaced Vegetabilia with Plantae in 1866, and recently the number of kingdoms rose as high as eight (Cavalier-Smith 1993). As of 2015, the number has fallen to seven, but if history is any indicator, this number will change in the future. In 2022, the seven are Animalia, Archaea, Bacteria, Chromista, Fungi, Plantae, and Protozoa.

While Carboniferous fossils exist for other kingdoms, such as Fungi, this page will focus on only two, Animalia and Plantae.

Taxonomists have different approaches toward plants, which makes getting a distinct phylum, class, order, and family difficult. There are several layers of clades and divisions named before the phylum. I’ve had a difficult time getting fossil plant specimens aligned to the same classification system used for Animalia. Many fossil plant specimens in the past received unique genus names despite later discoveries that they are two parts of the same plant. Often the unique detached portions of a plant get their own name, including the roots, the trunk, the branches, and leaves of different sizes.

For animals, the classification is simpler. Yet, taxonomists often erect sub and super designations for existing names. When they have a hard time coming up with a new family, they may add subfamilies to divide genera within. If an author determines that two families are similar, then they may describe a superfamily to group them. These subs and supers are not something I’ve tracked in the past, as they add too much noise to taxonomic information. Many subgenera end up getting split into two distinct genera, it seems. For example, White in 1884, described Soleniscus (Macrocheilus) paludinaeformis, with Macrocheilus as a subgenus to Soleniscus. But today, we know it as Strobeus paludinaeformis.

Classes or Phylum of life found locally

The following types of life by scientific name are available locally:

- Anthozoa (Rugosa Corals)

- Bryozoa

- Brachiopoda

- Mollusca

- Bivalvia (Clams)

- Cephalopods (Squid)

- Gastropods (Snails)

- Plantae (Plants)

- Trilobita

- Crinoidea

- Chondrichthyes (Cartilaginous fishes)

Anthozoa – Rugosa Corals

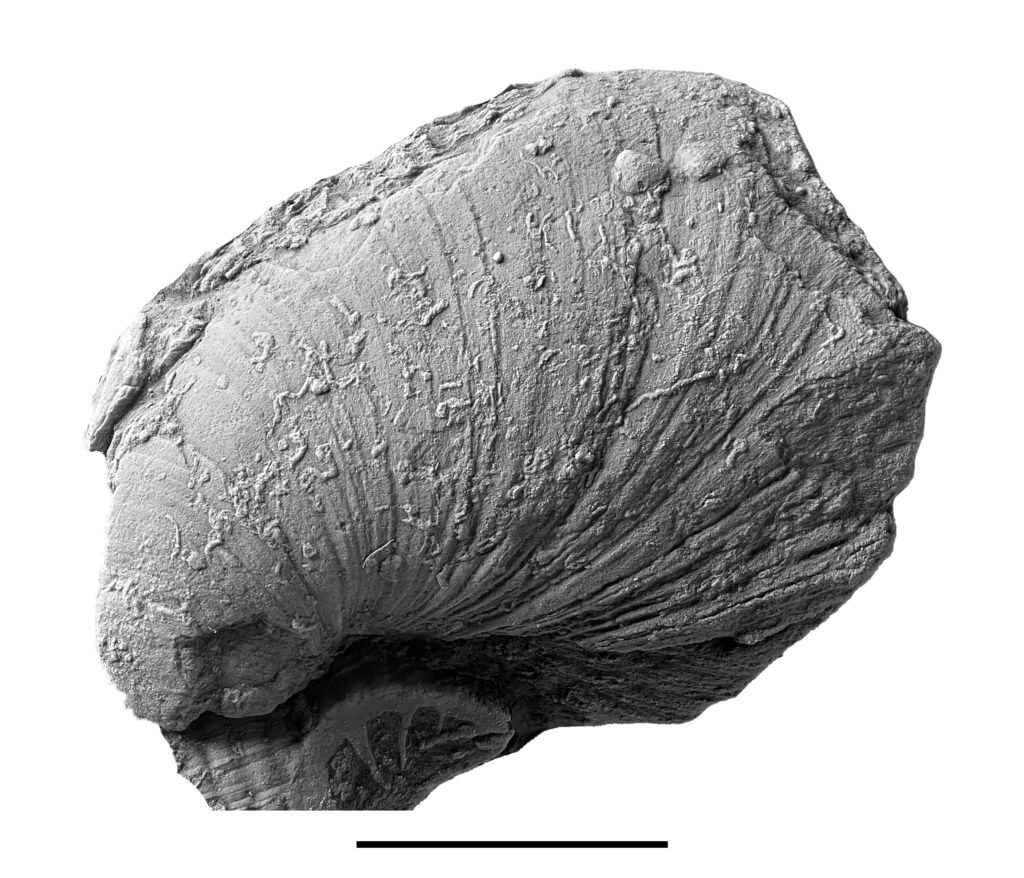

Horn corals are somewhat abundant in Brush Creek Limestone locally. The particular order is Rugosa. It is common to find these locked in limestone, and they are difficult to remove cleanly. In contrast, horn corals from the nearby Pine Creek limestone are simple to extract.

One of the more interesting things about these is their use as evidence for the rate of spin for the Earth. In modern corals, there are approximately 365 growth lines generated per year. Every day the coral adds a little bit of material and creates a growth line. Once a year, there is also a thickening of these lines, likely due to changing temperatures or the environment. The growth line count was 385 to 390 in Carboniferous Rugose corals. This correlates with the known phenom of the Earth’s rate of spin slowing as the Moon exerts tidal drag. In conclusion, the length of a day was shorter back in the Pennsylvanian period. A shorter length of the day means more days in a year, which was around 387.

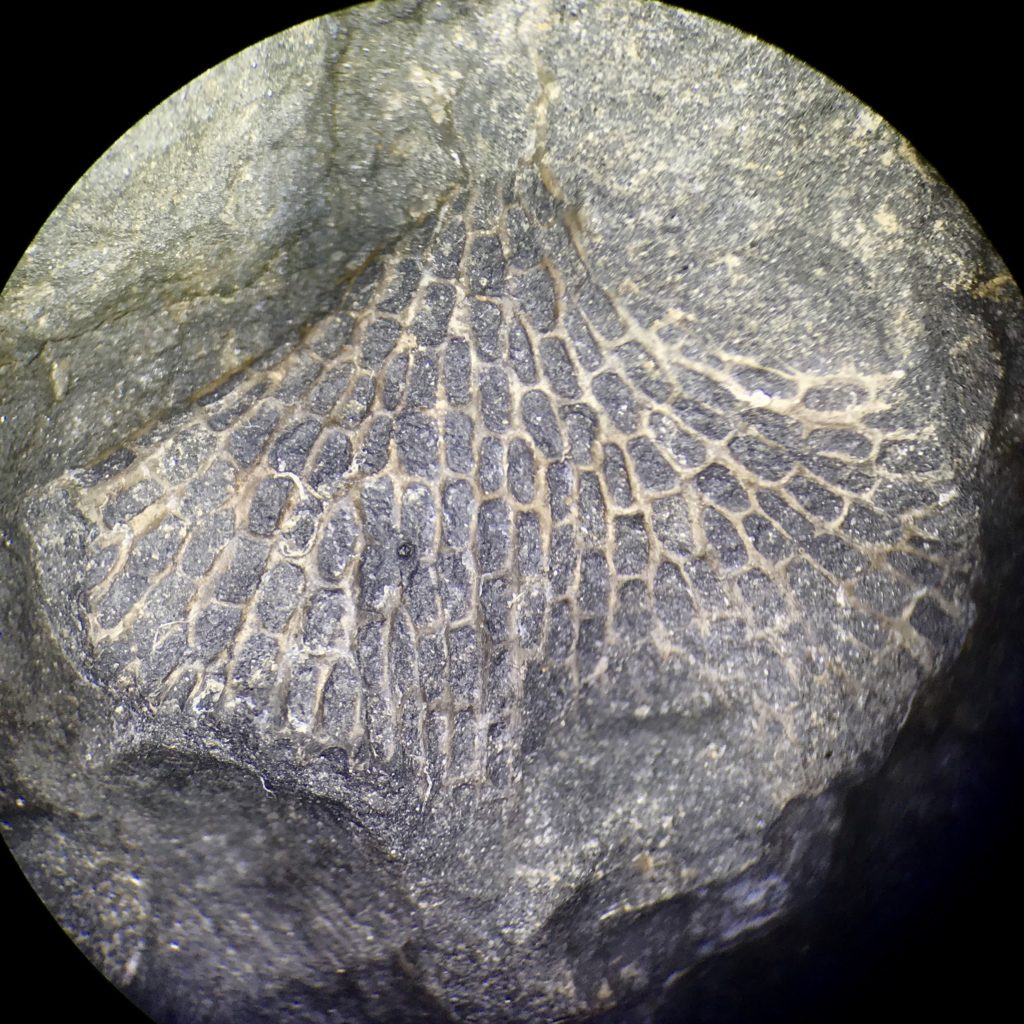

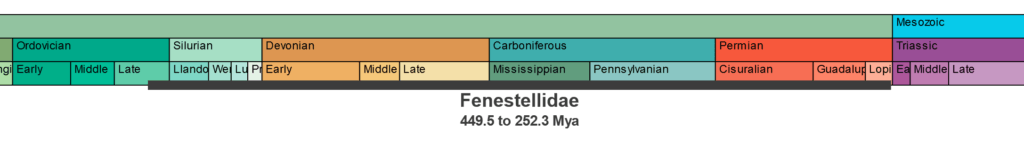

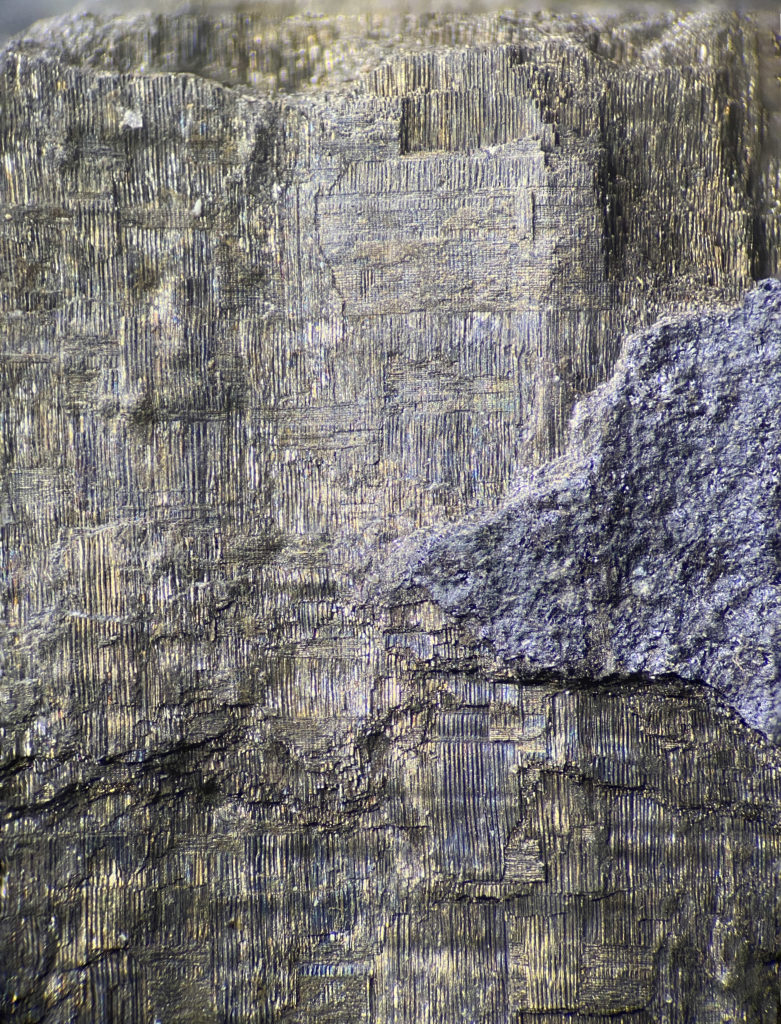

Bryozoan

These are quite beautiful finds when they show up. They are common, but I often find them broken up into pieces. The net-like matrix of openings were the living chambers of the animal. Each compartment holds between two to eight individuals. The number is known as each leaves two tiny rimmed pores in the front of each branch.

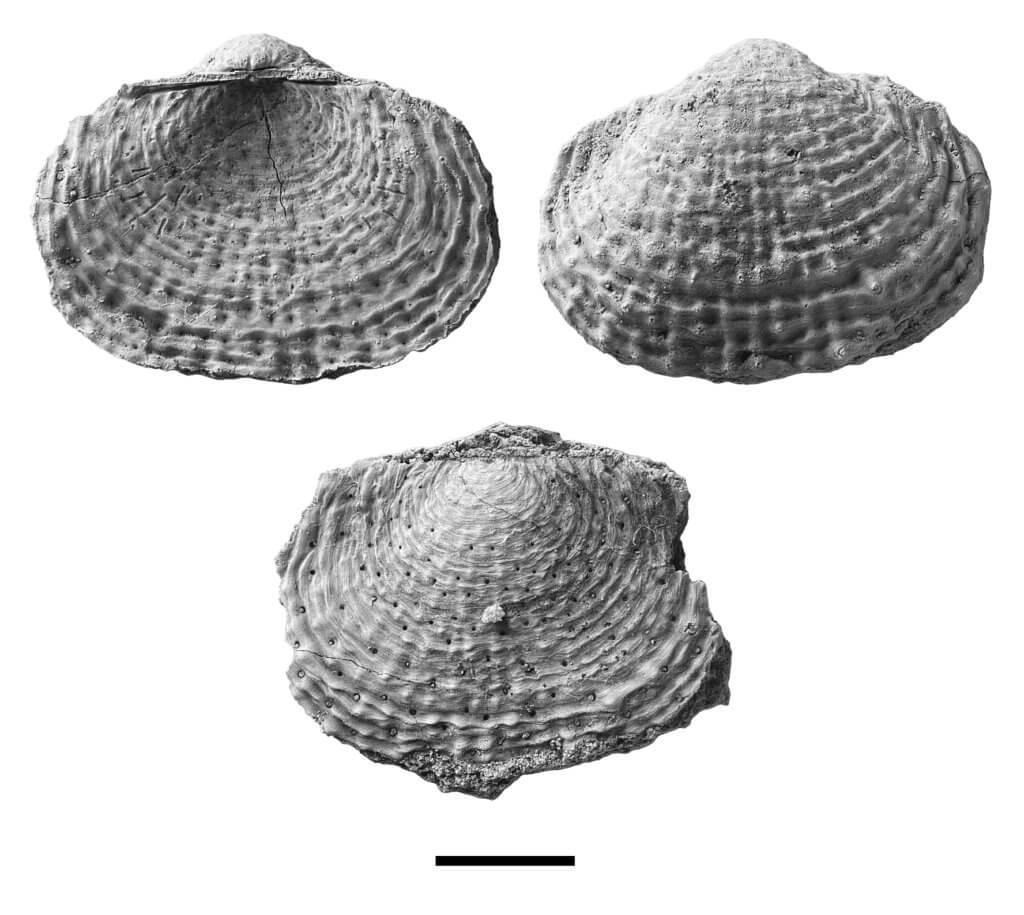

Brachiopods

Brachiopods are a very common find in the limestone stratum. While clams have a mirrored appearance between two shells, brachiopods have a mirrored appearance across each shell. For example, if you look at a particular shell from above, the left and right will be a mirror of each other. In clams, they will not be, with the left differing from the right most of the time.

Several different genera are available. Therefore, the following listing does not represent all species.

Brachiopod genera found include:

Mollusca

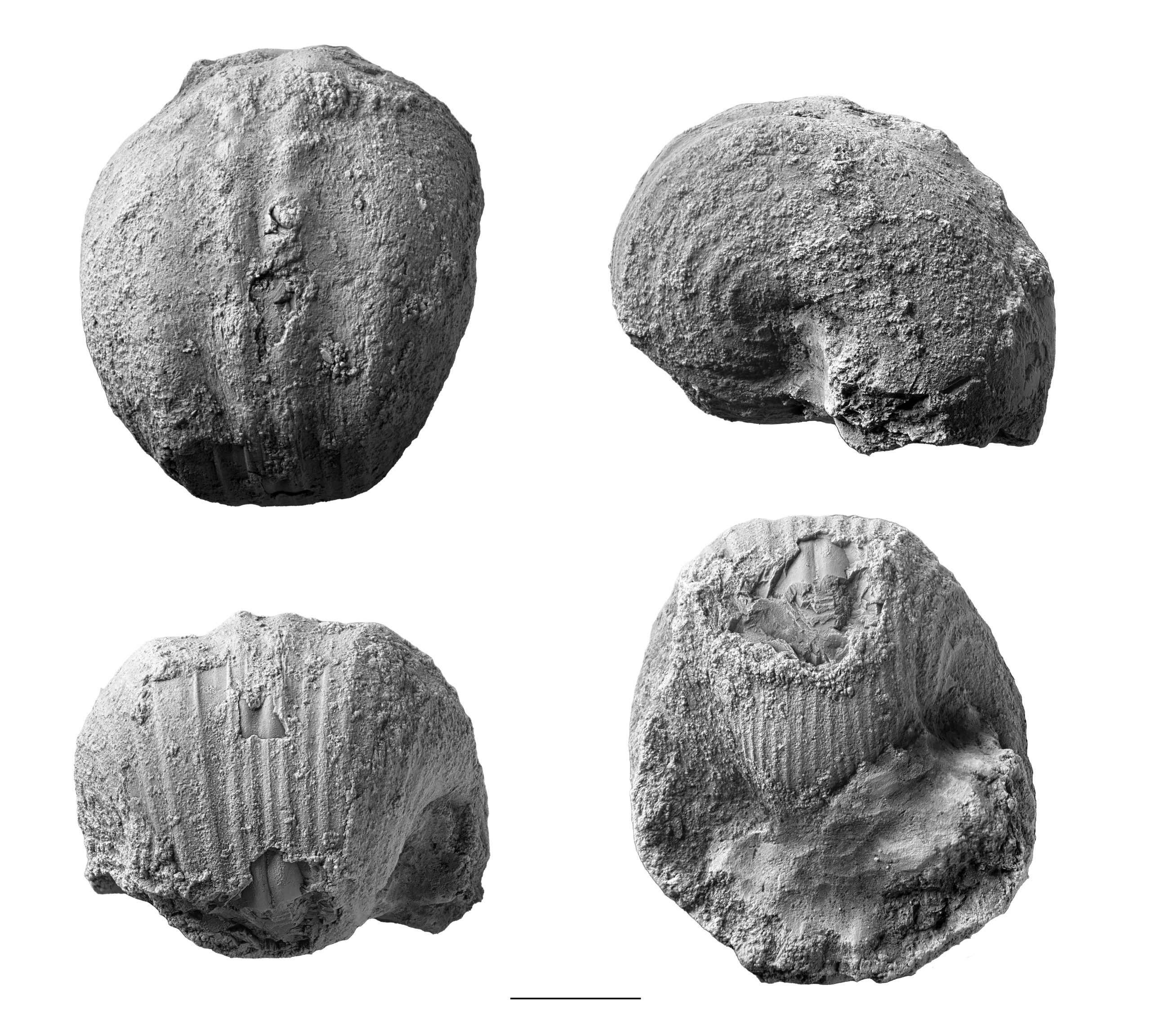

Bivalvia (Clams)

Clams have a shell that is a mirror image across the two valves (shells). They are often found as a single valve, but some have both valves still together. These include Wilkingia and Meekopinna. In the case of “Aviculopinna“, they buried themselves upright in the ocean sediment and usually die in the same position. Some genera such as Wilkingia bury themselves partially in sediment. Shells recovered with both valves together likely buried themselves during life.

Fossil bivalve genera include:

- Astartella

- Dunbarella

- Edmondia

- “Aviculopinna“

- Schizodus

- Paleoneilo

- Parallelodon

- Wilkingia

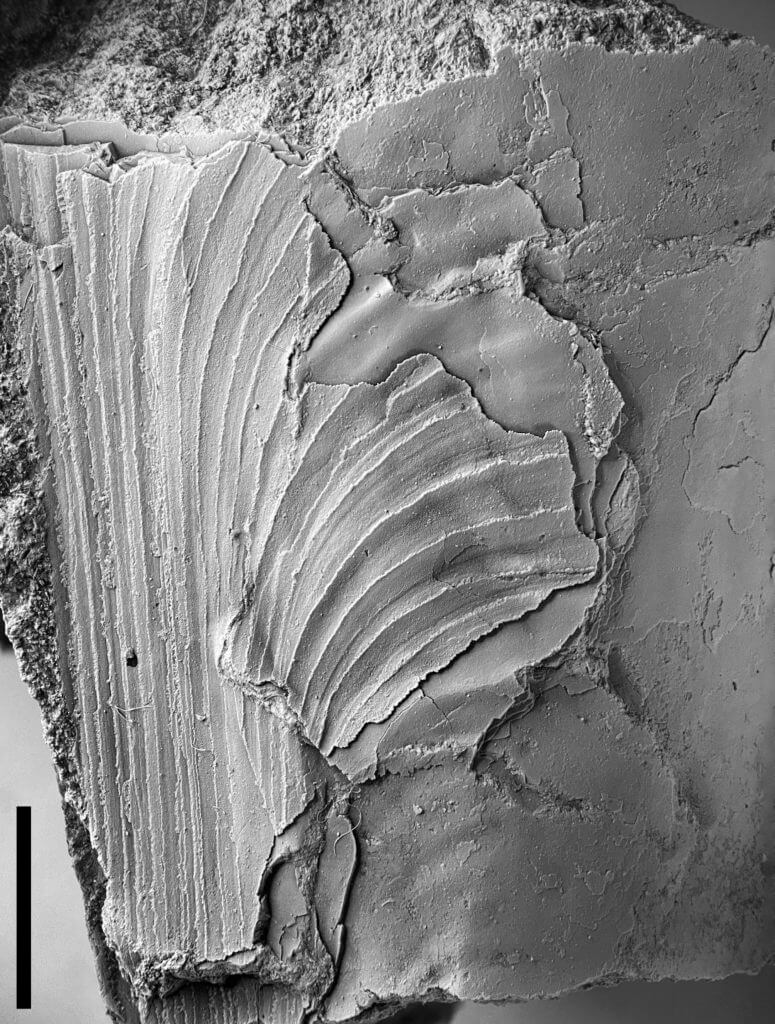

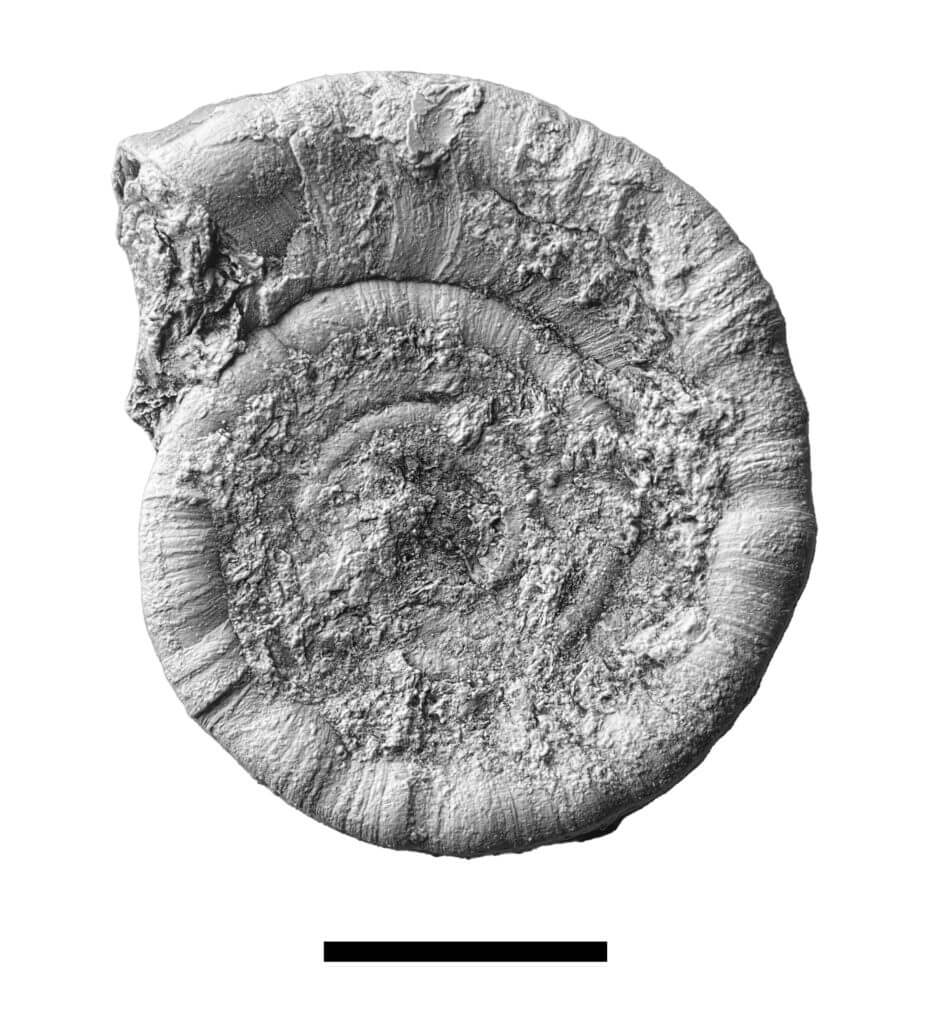

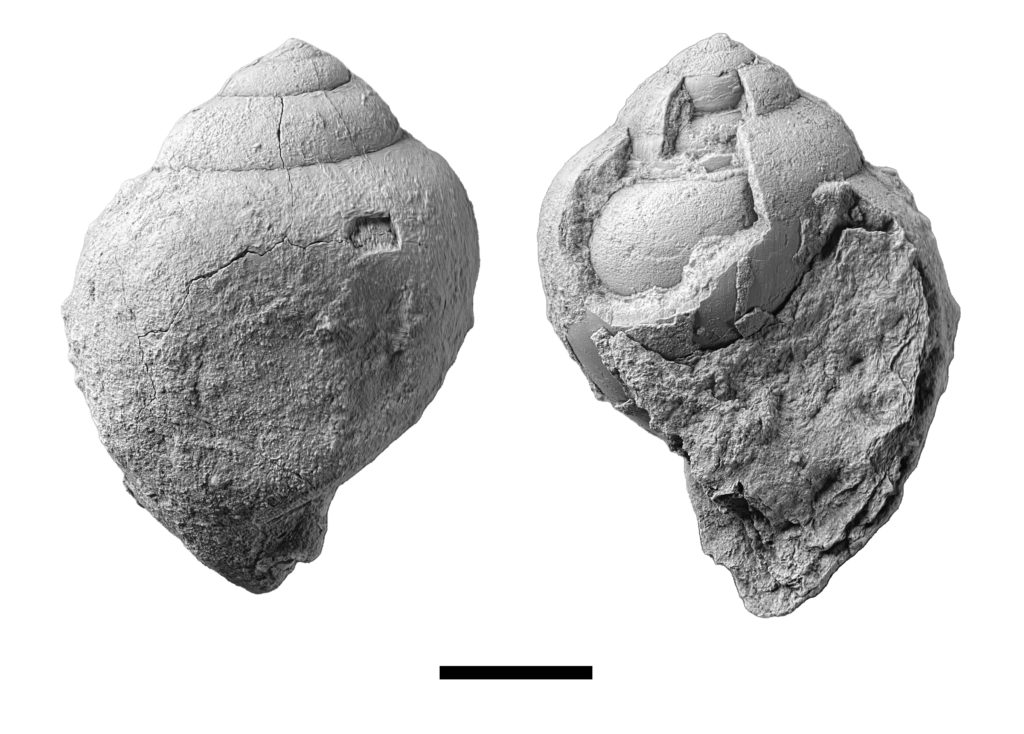

Cephalopoda (Squid)

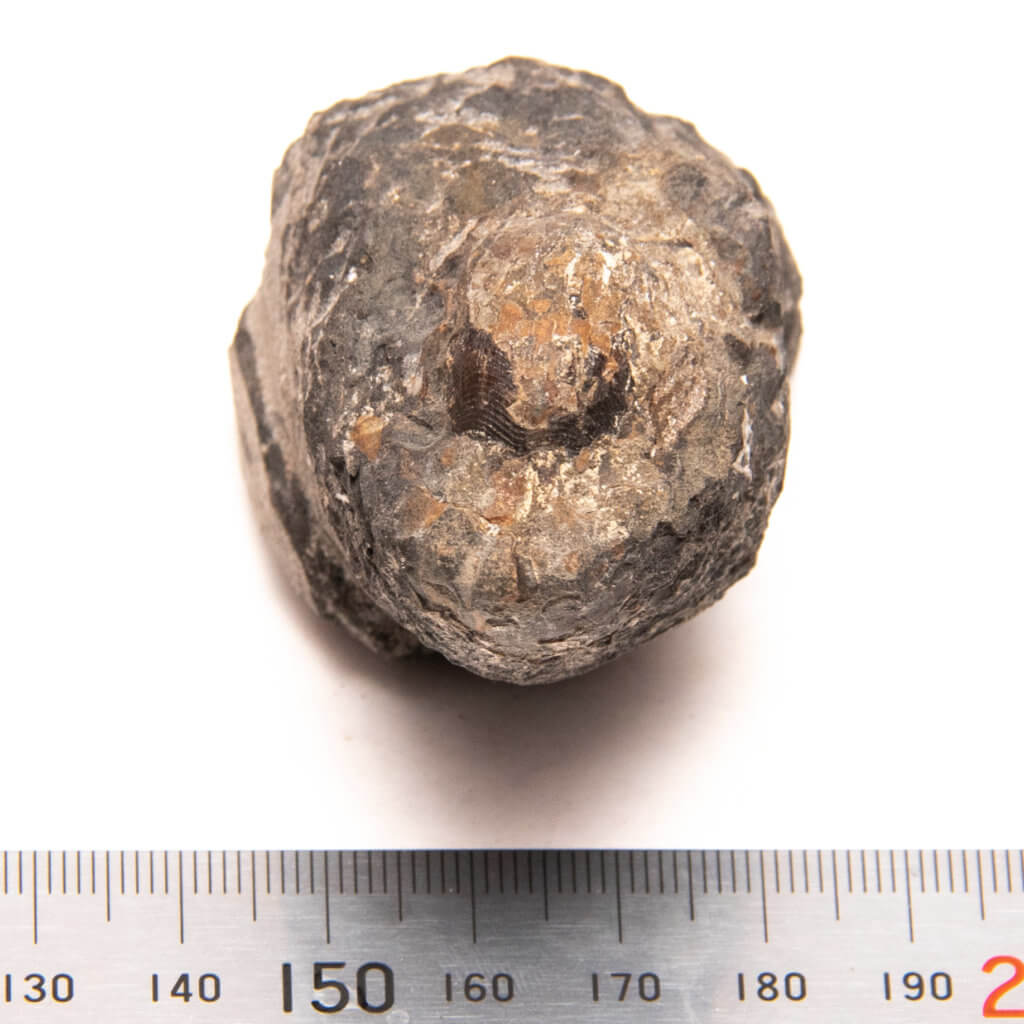

Cephalopod shells are an enjoyable find and some of the larger invertebrate fossils that can be recovered. Some species have shells as large as a soccer ball, but it’s rare and difficult to find one so large. The shell exteriors in the Brush Creek limestone tend to adhere to the rock, often leaving a steinkern form. Each chamber has a wall that attaches to the outer shell wall. This attachment is often seen in fossils preserved as steinkerns.

There are two base subclasses available. These are Nautiloid and Ammonoidea. Nautiloids are by far the most common. Ammonoids are found in the late Pennsylvanian, but their occurrence is rare in comparison. Nautiloids typically have straight-walled chambers, while Ammonoids have more intricate patterns. To further complicate things, Ammonoids divide into a number of different orders that typically differ with pattern complexity.

Nautiloids

Nautiloid genera found are:

Ammonoids

For comparison’s sake, As of December of 2021, I have only recovered a handful of confirmed Ammonoid specimens. There is also one additional piece that is unconfirmed. They are:

- Two from the order: Goniatitida? – A specimen with an Ammonoid pattern, but further identification is unlikely.

- Three from the genus: Schistoceras

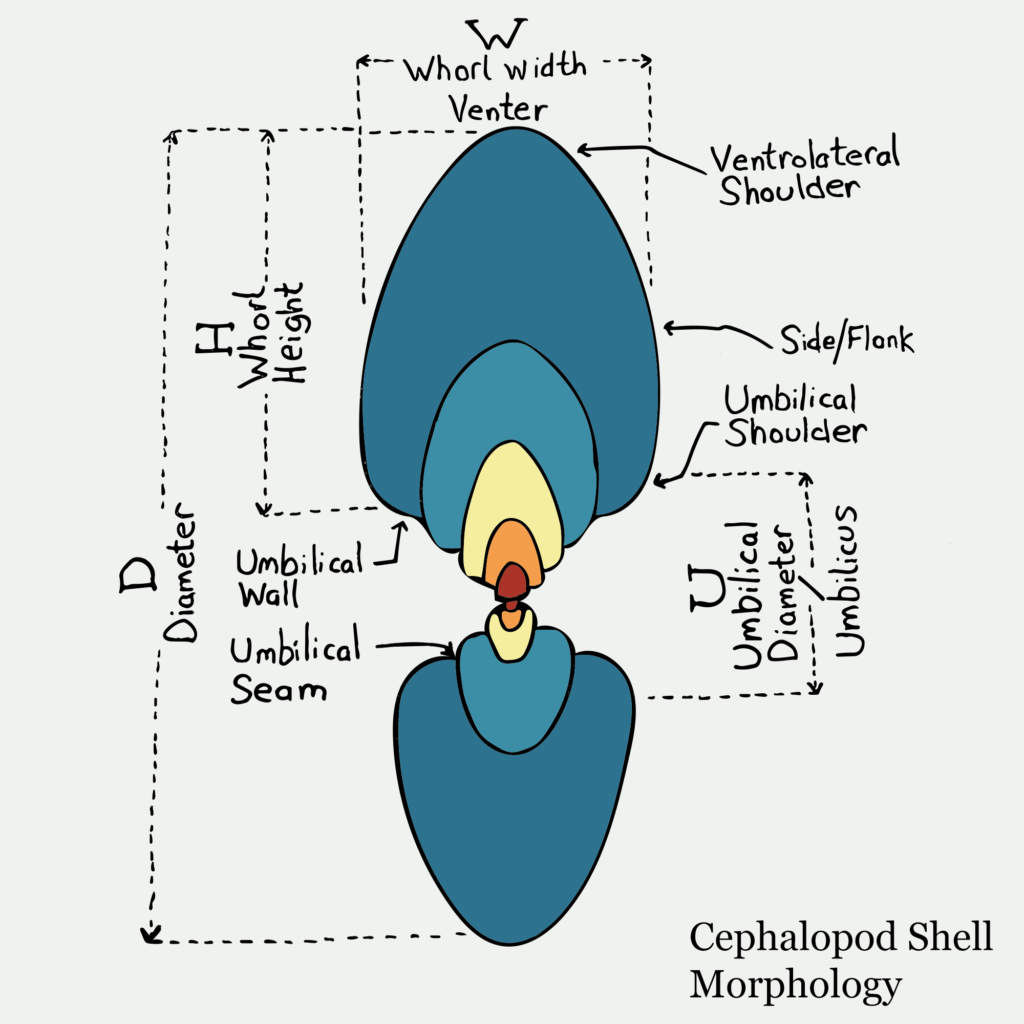

Cephalopod Shell Morphology

Shell terminology for descriptions of recovered fossils can take a while to memorize. There are several terms available for the different parts of each shell. The outside wall is the venter and the sides are considered the flank. The number of whorls is commonly reported.

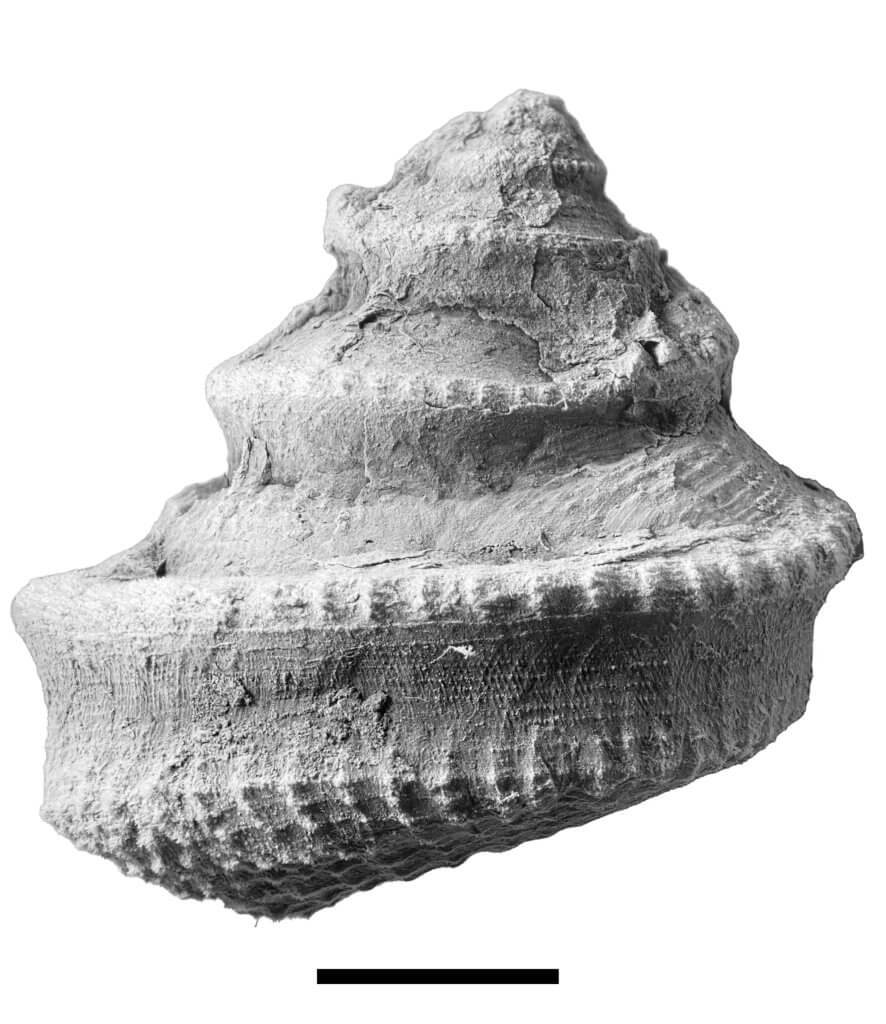

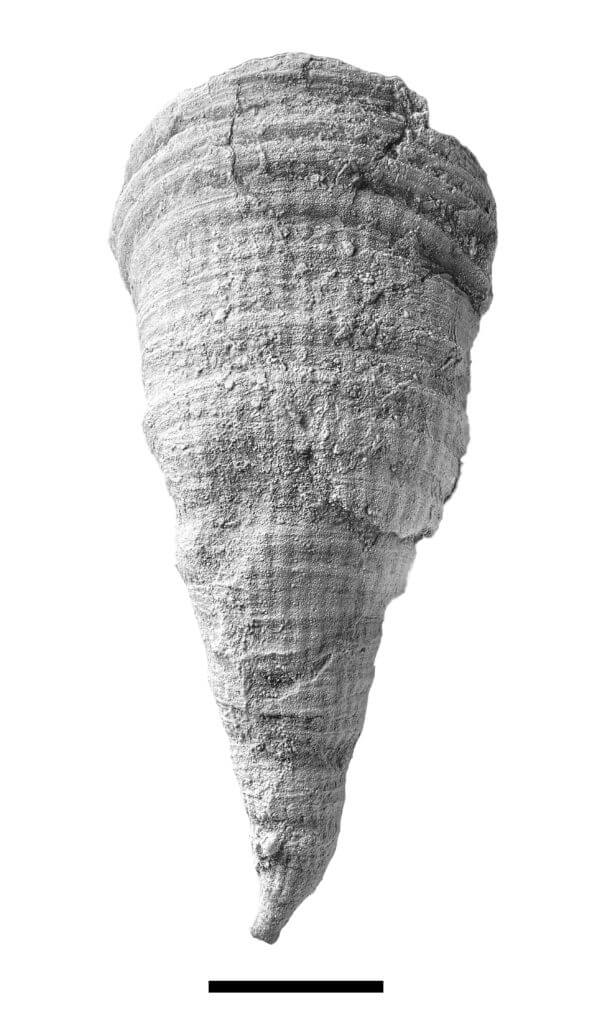

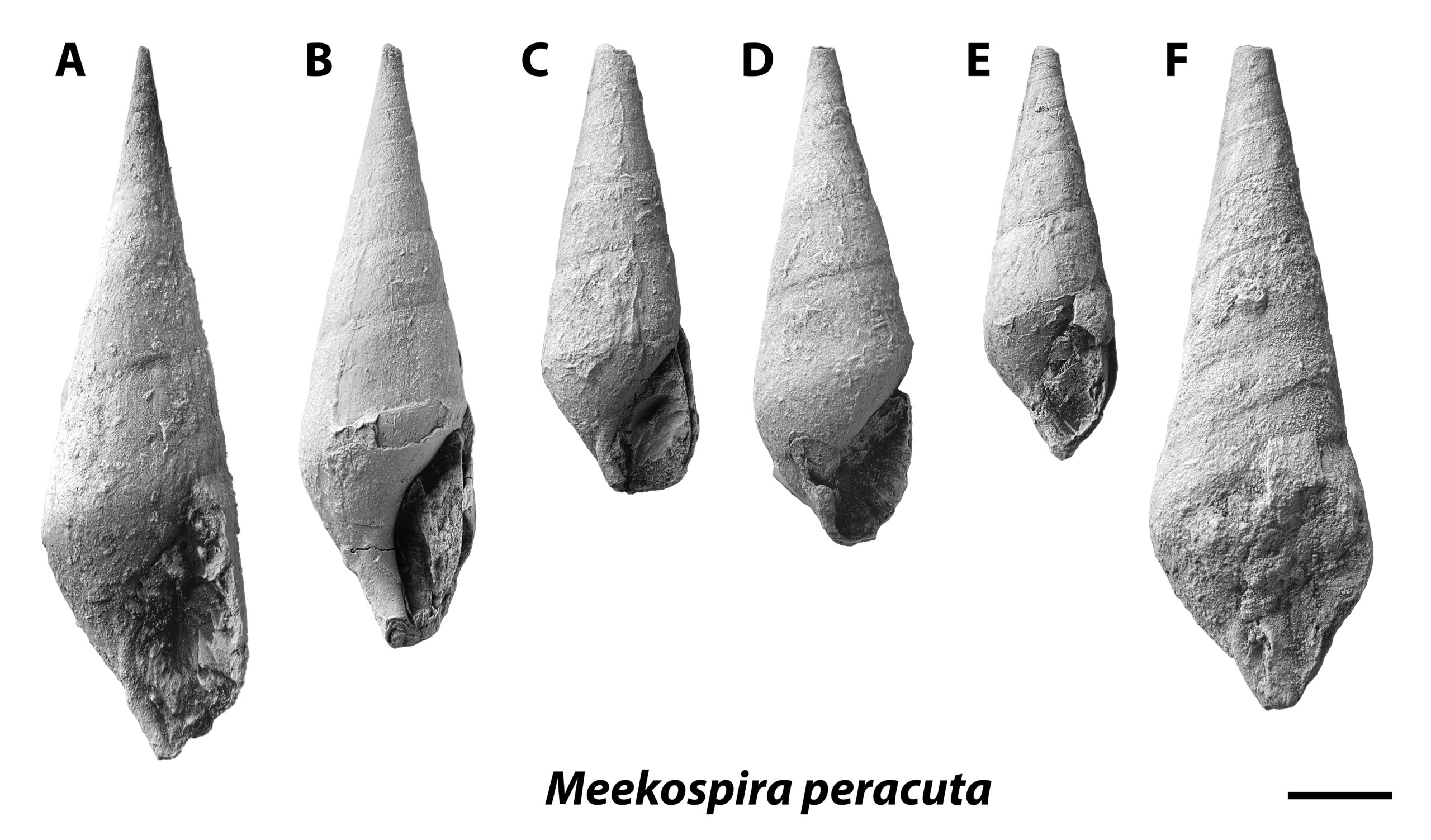

Gastropods (Snails)

Gastropods are found in marine, freshwater, and land sediments. Few creatures can bridge these realms, but gastropods can thrive in all. Even here in Parks Township, you can find late Pennsylvanian fossilized marine gastropods on rocks that have living land gastropods attached to them. In local lakes, large gastropods feed within the muddy sediments of the lake shorelines.

At least a dozen unique genera of gastropods are available to find in Glenshaw rocks, and I suspect that number is more than double. The cataloged finds locally include:

Late Pennsylvanian Gastropods from the

Glenshaw Formation in Western Pennsylvania [PDF]

Plants (Kingdom: Plantae)

Plants are another very large group that exists in all known common environments. From the sea to lakes, to the land, plant fossils can exist in several different places. Carboniferous rocks are famous for large coal deposits, which came from large areas of swampy land that were full of plant material. Coal strata were one of the major named things in most early geology literature. They were commercially important for producing heat and energy for industrial processes, and for heating homes. An early geologic map of the Freeport quadrangle featured locations of current and former coal mining operations. At some point, many western Pennsylvania towns had one or more operating coal mines.

One of the most common plant fossils is fern fronds. These are preserved as thin carbon film often in shales. In my observations, they also can leave an impression on the rock, albeit it is a very small one. The stems and larger pieces can leave deeper ones. The carbon films are striking when first exposed, and can dull after exposure to air. They are also not always black in color, with recovered examples of white, red, and other colors.

Plant identification

Identification of fossil plants can be difficult, as many different parts of the plant can have unique names. The roots, the trunk, the branches, lower leaves, mid leaves, upper leaves, seeds, and spores can all possibly have a name. The majority of specimens are found disarticulated, with no reference to the complete lifeform. Only when they are found together can these gaps be corrected and names synonymized.

Leaves are pretty simple to catalog, as they have identifiable markings. Different types of bark can also help with the identification of large tree trunks.

Plant preservation in different environments

Plants are preserved commonly in three places. The most common and easy to recover is in shale. These recoveries are typically from a deposit of mud and silt that buried some sort of plant remains. Perhaps parts that washed away in a river, or settled in the bottom of a lake.

The second more common location is in sandstone deposits. Locally, larger pieces of plants are seen in sandstone deposits. These are difficult to recover, as the larger grains of sandstone break easily and often don’t allow recovery of a specimen using common tools.

The third is in limestone, however, this is a rare occurrence. Often when I find bits of plants in limestone, they are fossilized and replaced as pyrite. Another excellent find was a mass of plants preserved as a wavy surface with fine lines. When looking at it with a microscope, you can see bits of preserved carbon. While plant material certainly gets washed out to sea, the plant surviving and sinking into the sediment is much less common than say a marine shell.

Chondrichthyes (Cartilaginous fishes)

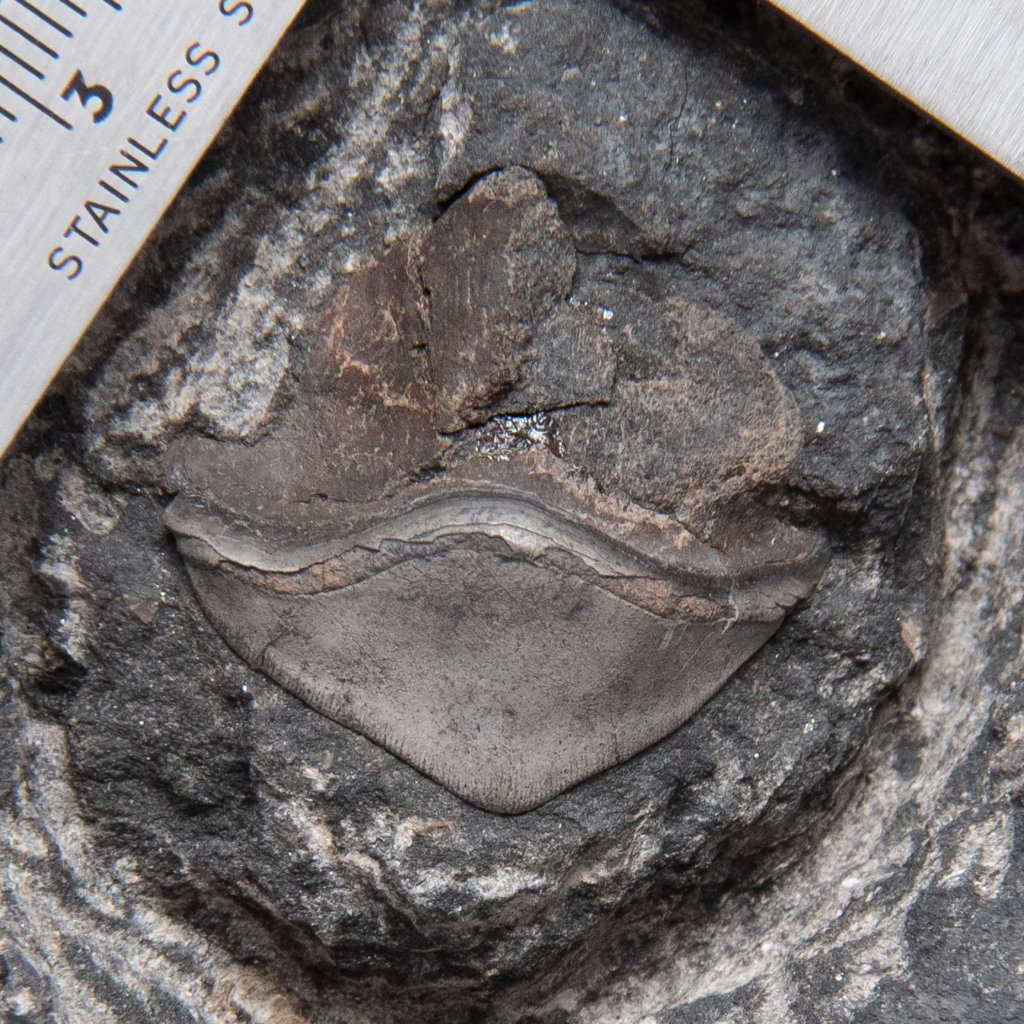

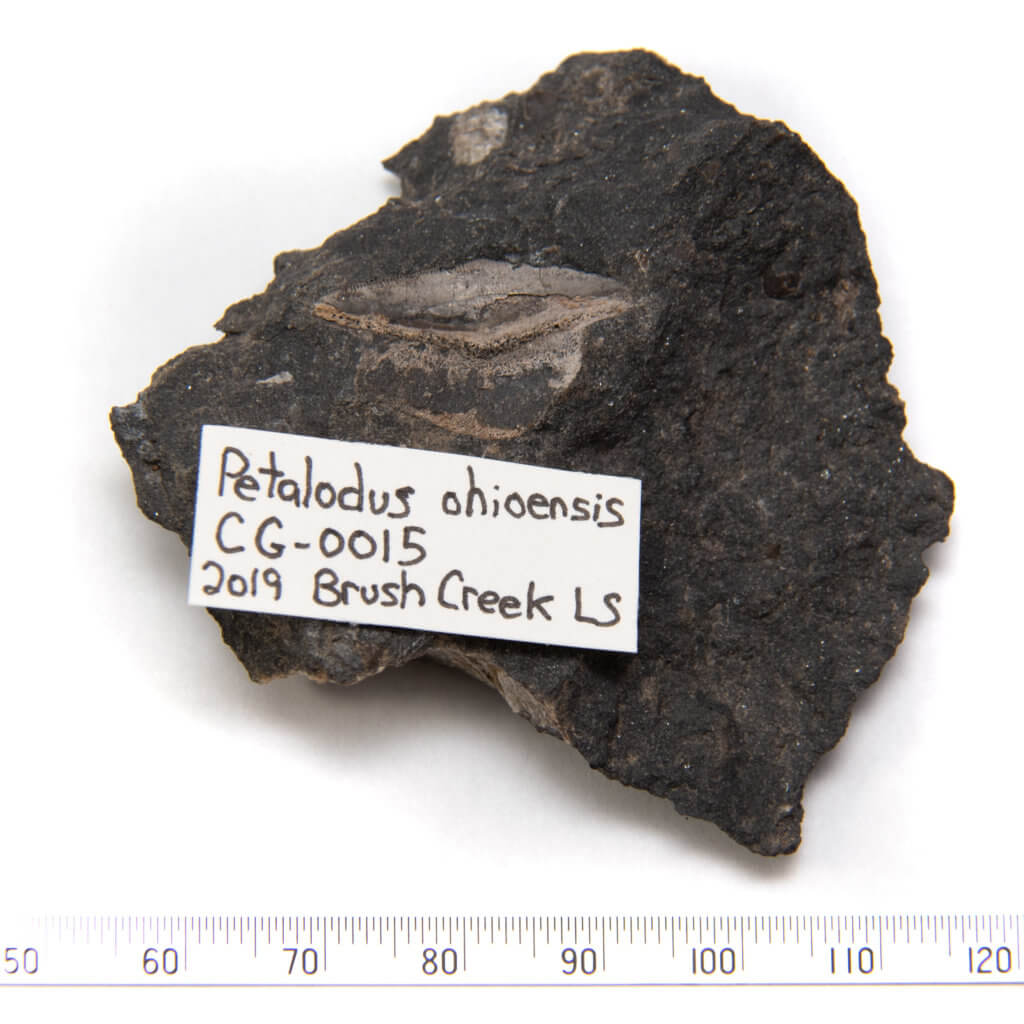

There are several types of fish teeth available to find in the Glenshaw Formation. To date, I have found two genera. Several specimens of Petalodus and a single example of Deltodus.

Deltodus has been a very rare find, with only one recovered specimen in three years of searching. Petalodus teeth are uncommon to rare. These teeth can be fragile and whole examples are hard to come by. Of the fourteen specimens in the catalog as of June 2021, only six of them have an entire crown.

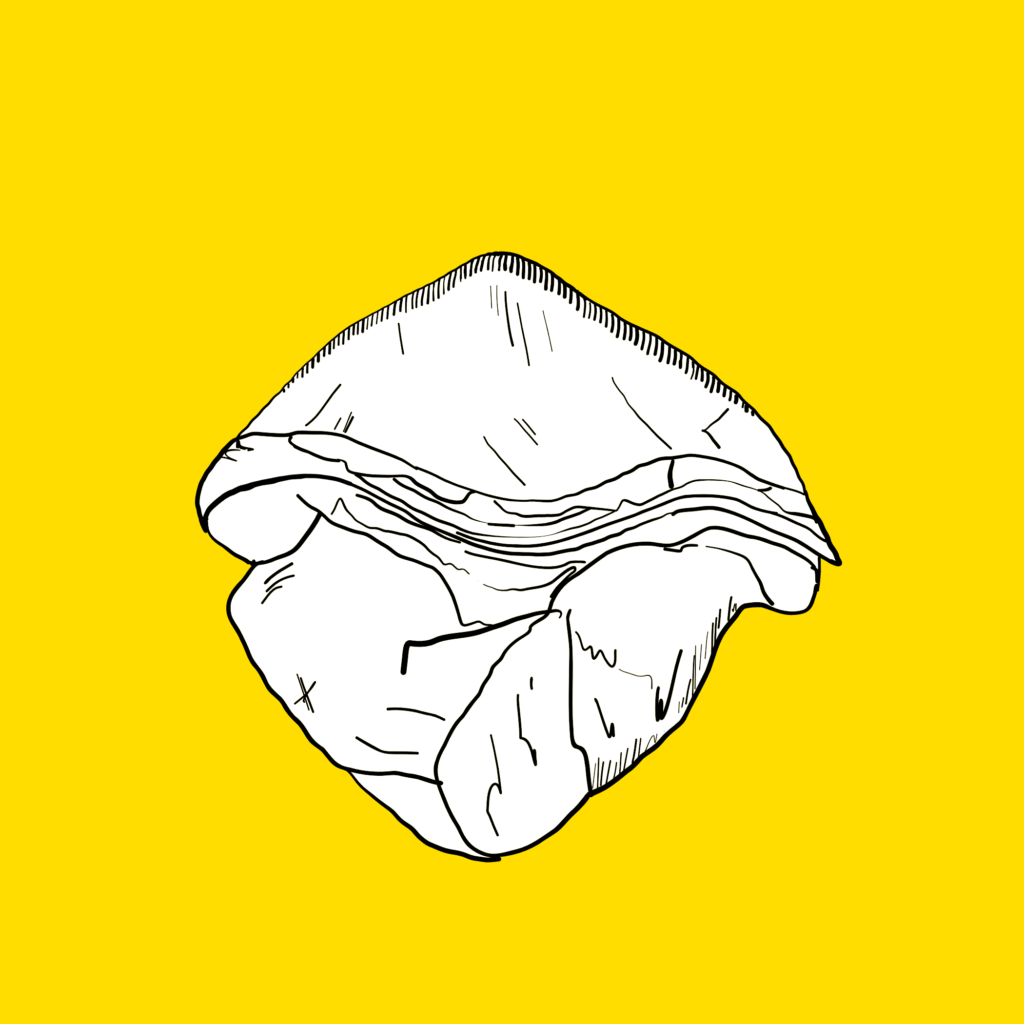

Some Background on Petalodus

All Petalodus specimens are of the species Petalodus ohioensis, the default for North American Petalodus recoveries. While there are likely more than one distinct species, it’s difficult to find differences using the teeth. The teeth are homodont, which means they all have the same function. Yet, each tooth’s position in the mouth determines the width and height ratio for each tooth. No discernable difference can be made from an array of variations that extends from the front teeth to the back.

Also, Petalodus is a member of the Cartilaginous fishes, so they should have a skeleton made of cartilage, the same as modern sharks. These types of skeletons are rare to preserve, and despite a known existence of 185 years, nobody has recovered a fossil of the body or even a jaw containing any teeth. The closest are two recovered specimens from a sibling genus.

References

- Fenestella (bryozoan) – Wikipedia

- 1966, Wells, J. W., Paleontological evidence of the rate of the Earth’s rotation. pp. 70-81, in: B. G. Marsden and A. G. W. Cameron (eds.), The Earth-Moon System, Springer.