Phylum Chordata Haeckel, 1874

Class Chondrichthyes Huxley, 1880

Order Petalodontiformes Zangerl, 1981

Family Petalodontidae Newberry & Worthen, 1866

Genus Petalodus Owen, 1840

Species Petalodus ohioensis Safford, 1853

Petalodus is the most common Pennsylvanian-aged macrovertebrate fossil in Armstrong County, represented only by preserved teeth. These fossil “sharks” had jaws full of cutting serrated teeth but are not like sharks today. Modern sharks belong to the same class, the Chondrichthyes, defined as “fishes having a cartilaginous skeleton.” With skeletons made of cartilage, the bodies did not preserve well. Despite the volume of dental specimens, the fossilized body or jaw remains undiscovered worldwide. All current reconstructions of the creature (See Hansen, 1996; Robb, 2003; Lucas, 2011; Harper, 2016) are based on the recovered body remains of the sibling genera found within its class, the Chondrichthyes.

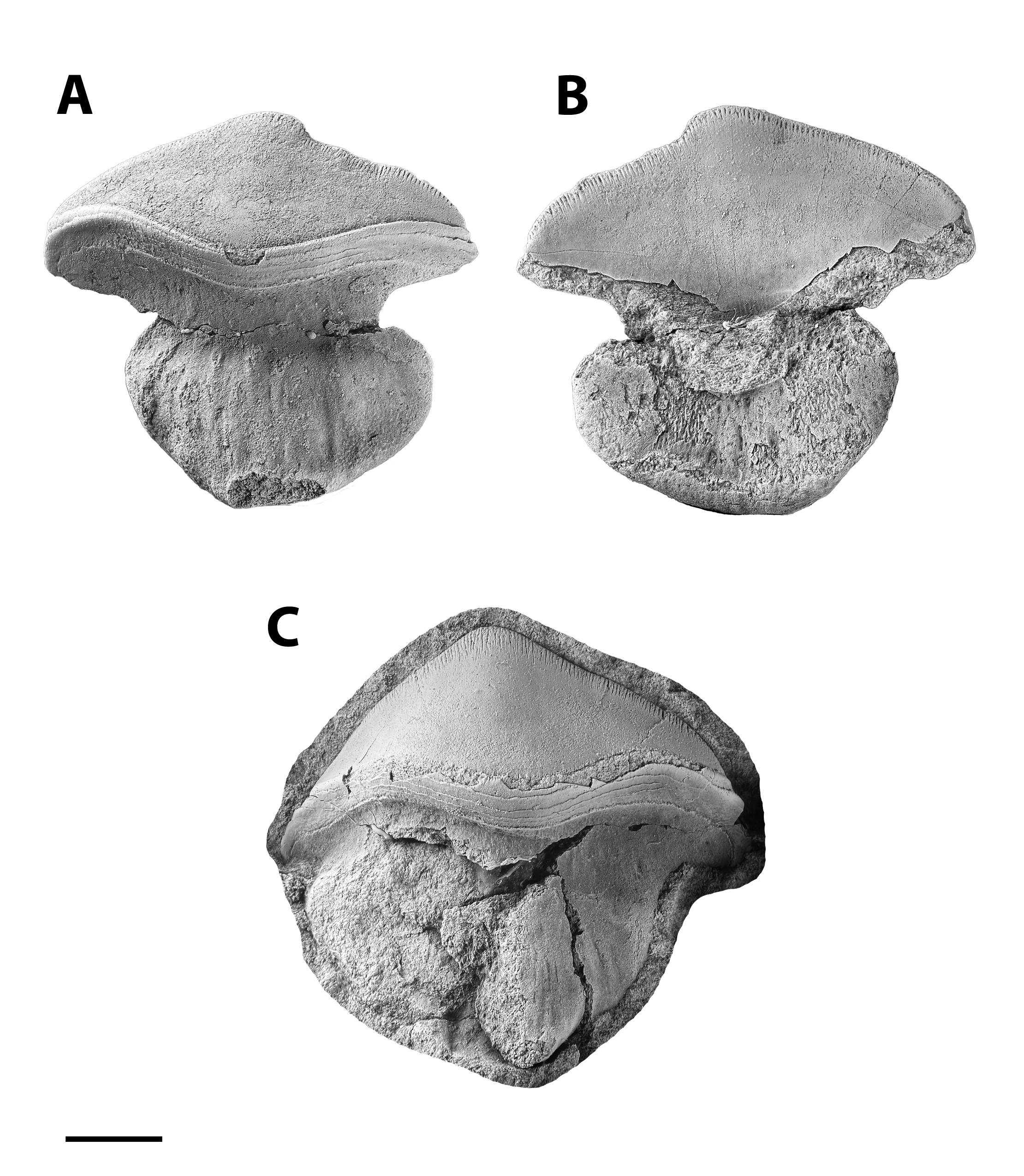

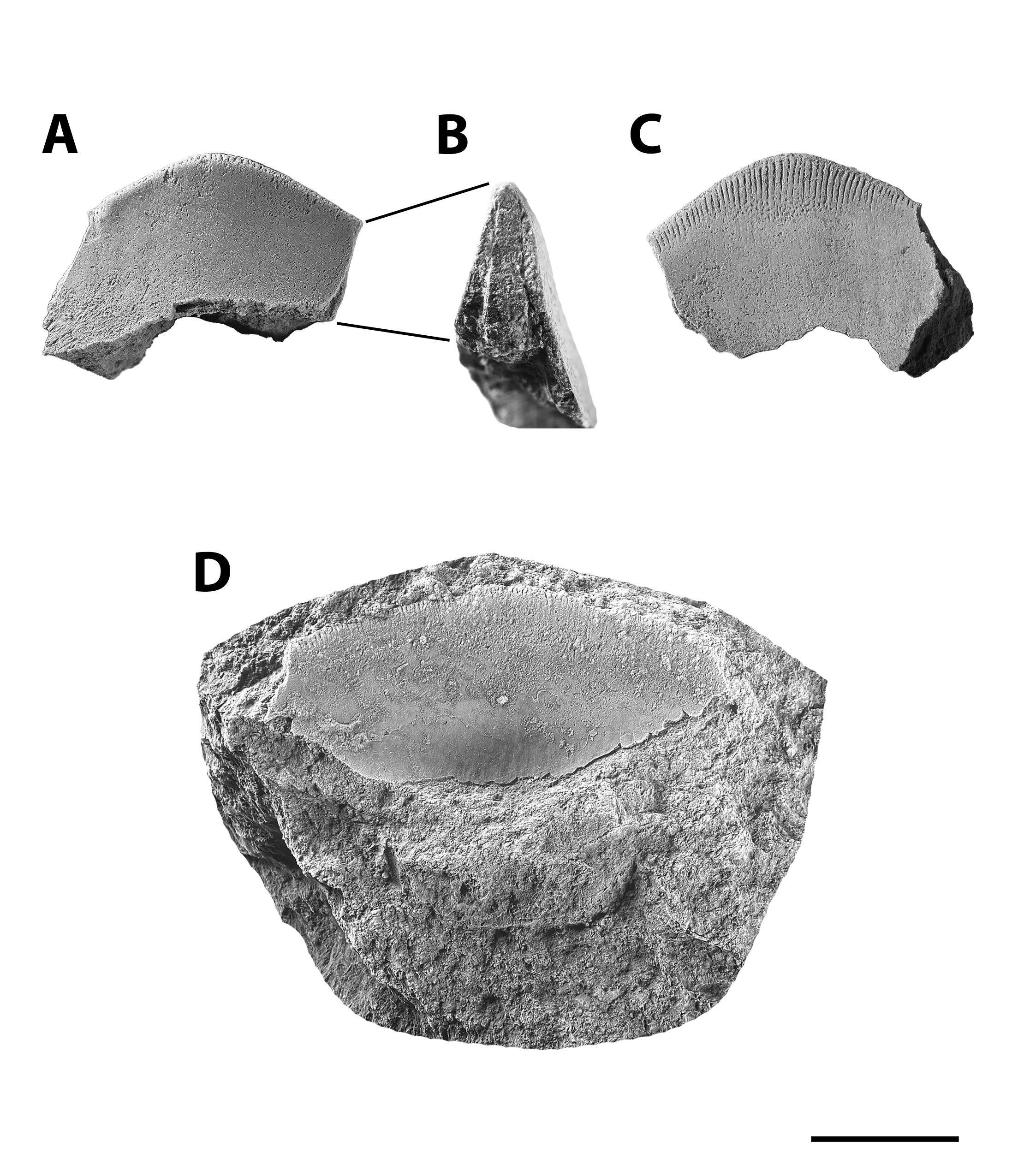

The teeth of the genus are homodont, meaning that all teeth are of the same morphology. However, this does not mean they all look the same. The crowns of teeth towards the back of the mouth are horizontally elongated; the ones toward the front are nearly as tall as they are wide. The root commonly preserves with the tooth and is most elongated on the front teeth. The transition between the crown and root presents with a feature named the distal crown tongue, composed of imbricated ridges that run the length of the margin. In the side profile, the individual teeth are sigmoid in shape or, more simply, an S shape. The teeth have crowns made of fossilized enamel material known as orthodentine. Several vascular canals can be observed throughout broken specimens. Zangerl et al. (1981) wrote a comprehensive manuscript about the dental anatomy in the Petalodontida that includes several photos and figures of the concept. The authors suggested that since both faces of the edges of crowns in Petalodus teeth appear worn equally in most specimens, attrition occurred through interaction with the environment and each other.

One of the most challenging things concerning Petalodus research is how named species in the past correlated with different parts of the animal’s mouth morphology. The difference between single specimens can be quite striking. There are two typical arrangements: those with a high crown, those with a low crown, and many heights throughout. Differences in tooth morphology and geological and geographical location justified many new species.

Workers should identify teeth from Armstrong County as Petalodus ohioensis, the default species for North American Pennsylvanian Petalodus teeth. The species was first named in North America by Safford (1853). However, his report was published in an obscure journal and was missed by the authors when they reported new species. Like many early North American fossils, the holotype specimen is missing. Before its disappearance, workers cast two copies; one is deposited at the Yale Peabody Museum in New Haven, Connecticut (YPM 2861), and another—only recently found—sits at the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois (FMNH PF 673). The Yale Peabody cast represents Safford’s specimen, but the Field Museum cast is of greater detail.

Leidy (1856) erected Petalodus allegheniensis from a specimen recovered at Inclined Plane No. 3 of the Old Portage Railroad, Blair County, Pennsylvania, a location that correlates with the Brush Creek limestone in Armstrong County. He was unaware of Safford’s work and thus named the specimen a new species. Unlike Safford’s specimen, Leidy’s holotype exists, reposited at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (ANSP 14541). Hay (1895) later proposed a correlation between the two and committed to it shortly after (Hay, 1902).

Other authors named species from the United States, including those from the state of Nebraska (St. John, 1870), Iowa (Newberry & Worthen, 1870), Illinois (Newberry & Worthen, 1866; St. John & Worthen, 1875), Indiana (Newberry, 1879), and Kansas (Miller, 1957). Since authors named many new species based primarily on morphological shape differences and geographic location, all Pennsylvanian specimens from the United States should be identified under the senior name, P. ohioensis.

The volume of teeth collected across the two Armstrong County localities has been different. Personal fossil collecting from the Brush Creek limestone at SL 6533 has produced more Petalodus teeth over time, but this evidence is anecdotal. There is a clear difference in paleoenvironment between the two localities. Fossil crinoids, brachiopods, and pinnids are widespread in the Brush Creek limestone, while the Pine Creek limestone at SL 6445 lacks fossils of these types and contains more examples of gastropods.

References

- Agassiz, L., 1838. Recherches Sur Les Poissons Fossiles. Tome III (livr. 11). Imprimérie de Petitpierre, Neuchatel 73-14

- Harper, J. A., 2018. Reflections on Petalodus, a Common Late Paleozoic “Shark”1 Tooth Found in Western Pennsylvania’s Rocks, Pennsylvania Geology V. 48 No 2, pp. 3-11

- Hay, O. P., 1902. Bibliography and catalogue of the fossil Vertebrata of North America. U.S. Geological Survey, Bulletin 179, 868 p.

- Itano, W., Carpenter, K, 2020. High-quality Casts of the Missing Holotype of Petalodus ohioensis Safford 1853 (Chondrichthyes, Petalodontidae) at the Field Museum of Natural History and their Bearing on the Validity and Priority of the Species, Geology of the Intermountain West, V. 7, pp. 197-203.

- Leidy, J. 1856. Descriptions of some remains of fishes from the Carboniferous and Devonian formations of the United States. Journal of the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia, 2nd Series, 3, p. 159-165.

- Miller, H. W., Jr., 1957. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, Vol. 60, No. 1, Petalodus jewetti, a New Species of Fossil Bradyodont Fish From Kansas, pp. 82-85

- Owen, R., 1840. Odontography; or, A treatise on the comparative anatomy of the teeth

- Robb, A. J., III, 2003. Notes on the occurrence of some petalodont shark fossils from the Upper Pennsylvanian rocks of northeastern Kansas: Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science, v. 106, no. 1/2, pp. 71–80,

- Safford, J. M., 1853. Tooth of Getalodus [sic] ohioensis, American Journal of Science and Arts, V. 16, No. 46, p. 142.

- Worthen, A. H., Newbery, J. S., 1866. Geological Survey of Illinois, Vol 2, Paleontology.

- Zangerl, R., Winter, H. F., Hansen, M. C., 1993. Comparative microscopic dental anatomy in the Petalodontida (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii), pp. 16-23

Late Carboniferous Fossils from the Glenshaw Formation in Armstrong County, Pennsylvania

Preface | The Photographic Process

Localities: Locality SL 6445 Brush Creek limestone | Locality SL 6533 Pine Creek limestone

Bivalvia: Allopinna | Parallelodon | Septimyalina

Cephalopoda: Metacoceras | Poterioceras | Pseudorthoceras | Solenochilus

Gastropoda: Amphiscapha | Bellerophon | Cymatospira | Euphemites | Glabrocingulum | Meekospira | Orthonychia | Patellilabia | Pharkidonotus | Retispira | Shansiella | Strobeus | Trepospira | Worthenia

Brachiopoda: Cancrinella | Composita | Isogramma | Linoproductus | Neospirifer | Parajuresania | Pulchratia