In finding marine fossils in the Glenshaw Formation, I have noticed three distinct preservation types within the limestone. This observation does not say that there are only three, but these are the most common I have identified. All these involve the preservation of marine creatures’ remains in limestone. Marine limestone is a sedimentary rock that forms in warm shallow seas. Non-marine limestone forms in lakes, tufa deposits, etc.

Marine animals use calcium carbonate to create their shells, for living in, and for general protection. This calcium carbonate also precipitates, like continuous rain, over the seafloor. This material combines with sediment on the seafloor into limestone, which is a natural cement. A key ingredient in cement is lime from limestone, while cement is a critical ingredient in concrete. This rock formed hundreds of millions of years underground, with more and more sedimentary rocks adding compression from the crushing weight above.

The First Type: Standard Limestone

Some limestones are pretty hard to work with and it can be challenging to extract fossils. But, depending on its location, I have found three different preservation types of this rock. In the Brush Creek limestone, there is what I am calling standard limestone, which is very hard, heavy, and not prone to breaking. While there are some cleavage planes through these boulders, you need a hefty hammer to get them to split. Yet, it can be brittle when dry, with vertical splits crossing several cleavage planes. This limestone is no more than a foot thick in Parks Township, but it can be several feet thick in other places. The thickness depends slightly on how long the sea persisted and more on the sedimentation rate.

Specimens within have some unique properties. Steinkerns (molded representations of a creature created by filling hollow portions with sediments during the fossilization process) are solid, and made of this type of limestone. Any preserved shell-bearing marine creatures are difficult to extract as intact specimens. The outside, textured part of shells adheres to the matrix, while the smooth portions that face inward separate easily. So when you split a rock, and there is a fossil cephalopod, brachiopod, or gastropod on the cleavage plane, the shell will remain to one side, and the exposed steinkern on the other.

Unique Brush Creek specimen preservation

One unique trait for recovered finds from this type of limestone is the preservation of shell material on brachiopods and gastropods. These shells appear as a bright white color against the dark gray color of the limestone. Their shells consist of calcium carbonate, but it is only one of three naturally occurring crystal forms. It is white, likely due to the recrystallization of the original calcite shell. This unique preservation also occurs within the Pine Creek limestone, just not in the same way.

The Second Type: Weathered Limestone

While standard limestone is very hard, it is not one widespread unbroken rock layer in nature, especially over large areas. These pieces can be several different sizes, depending on their location. Some pieces are as large as a school desk, and some are as long and wide as a bus. These appear throughout the layer, but they may be only towards the exposed edges. In western Pennsylvania, synclines and anticlines are up-and-down folds of the stratum. This manipulation of once-level layers causes stress fracturing.

Even so, these fractures are margins in the rock that allow water to seep through. Over a very long period, this water creates a sort of rind on the outside of the stone. Float limestone lying in water goes through a similar transformation. The dark color turns brown, and most of the calcite within appears to dissolve away. There are many variations of these, with some still being a dark color and others being very light and brown. The color variation depends on the time of exposure to chemical weather agents like mineral-laden water.

Fossils found in this layer have some unique properties. They are often fragile, much like the matrix that surrounds them. They can be only a surviving steinkern or a shell that has changed properties. A find that prompted me to write this article was of a Metacoceras that had separated camerae (chambers in the shell). In standard-type limestone, these specimens hold together as one piece. The first type of limestone has a discernable calcite layer called the septum between each camera chamber. This septum is nearly absent in this type of stone. This type of preservation displays intricate details of each camera of the cephalopod’s shell. The empty chambers that filled with sediment are now each a steinkern.

Example Specimens from Weathered Limestone

The Third Type: Fissile Limestone

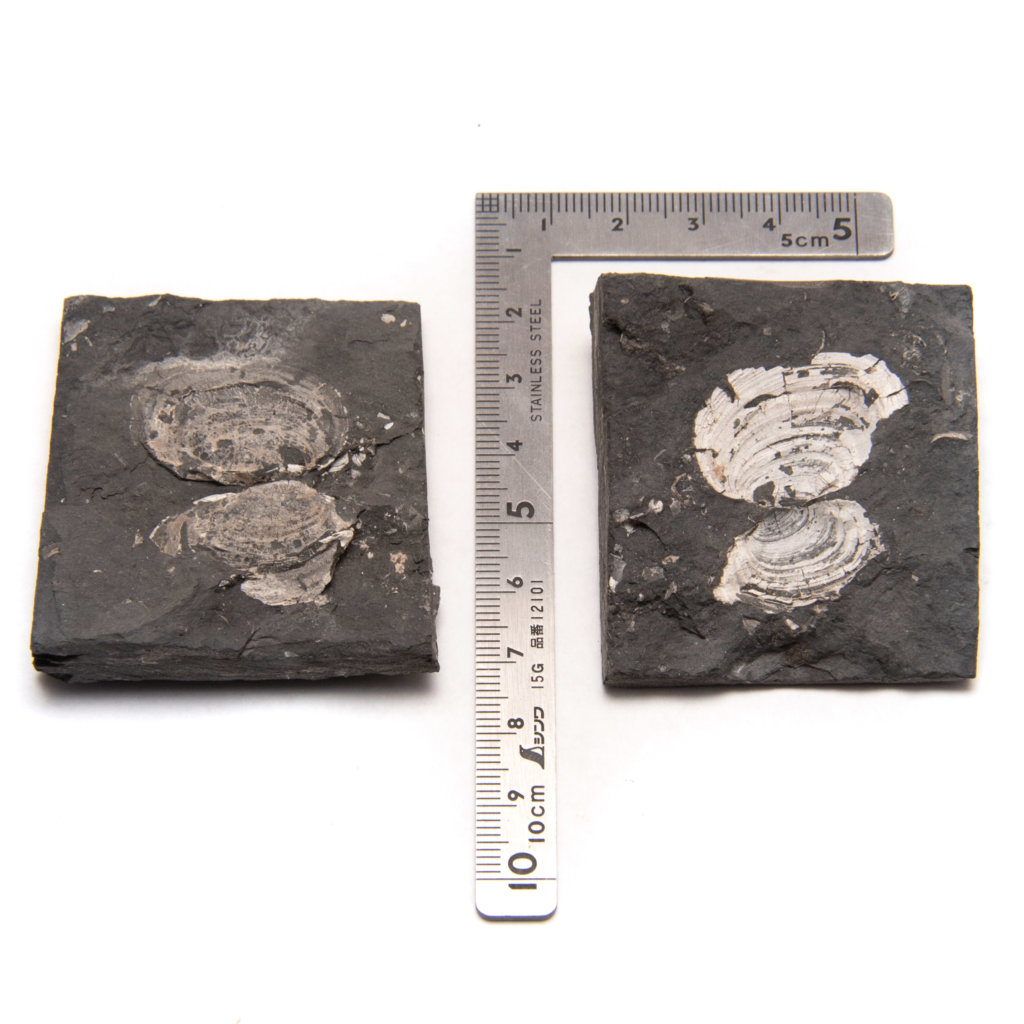

The third type is similar to the standard limestone. The critical difference is that it is very fissile. This quality has been present during my experience working with the Pine Creek limestone in the Kittanning area. This rock splits into many different planes. It is similar to shale. Specimens in this matrix preserve the aragonite as a white chalky material, identical to the first type. There are advantages to fissile limestone, but there can be problems with it as well.

Using cephalopods as an example, I have recovered preserved portions of the shell. The fissile nature of the rock helps it not to adhere to the shell, and I have been able to discover three-dimensional pieces of shells of cephalopods. Gastropods are another type that is easy to recover. The compact nature of the shells allows them to stay intact and fall out of the matrix when searching through them.

Example Specimens from Fissile Limestone

More Reading

- Geology.com – Limestone