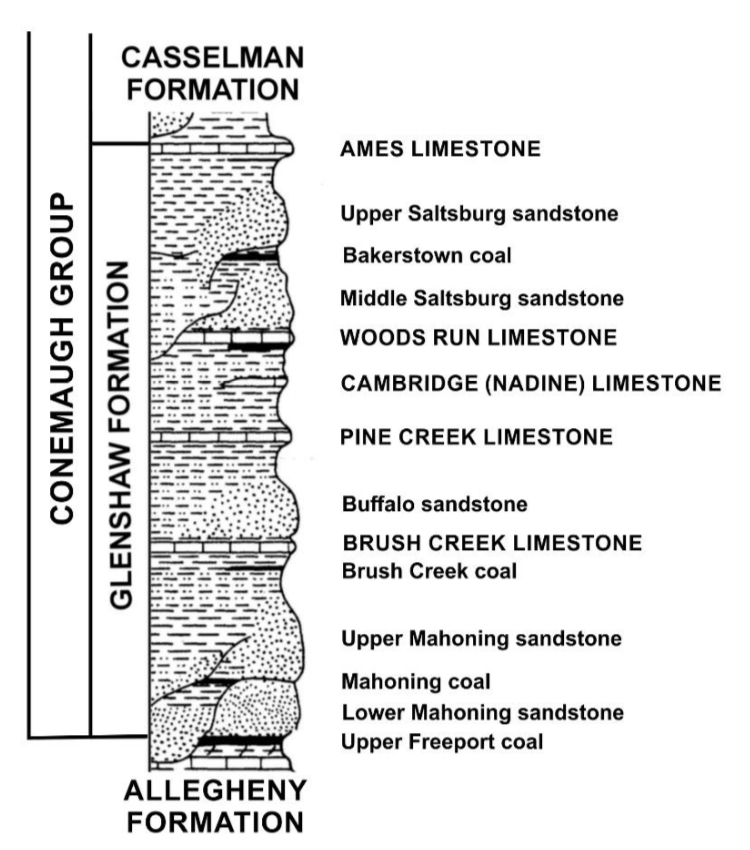

The Glenshaw Formation is where I find most fossils featured on this website. It is a type section named by N. K. Flint in 1965. The Glenshaw and the younger Casselman Formation comprise the Conemaugh Group, part of an entire third-order T-R unit.

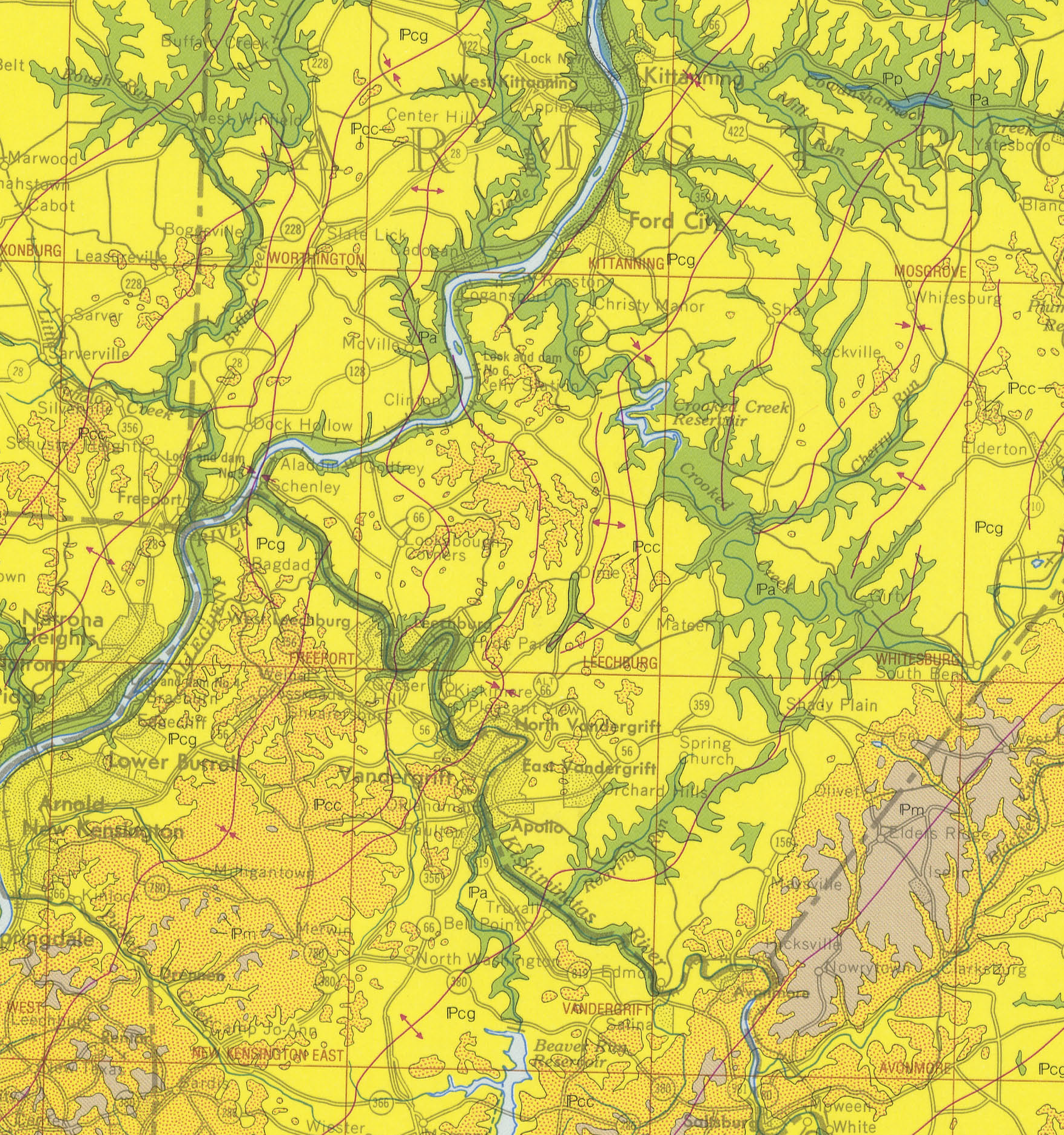

The top part of the formation locally is located on hilltops. You’ll find this boundary by discovering the extensive marine stratum, the Ames Limestone. If I look at lower elevations towards the Kiskiminetas River, the Glenshaw and the Allegheny Formation meet at the Upper Freeport Coal/Lower Mahoning Sandstone boundary.

The Glenshaw Formation contains both marine and plant fossils in Western Pennsylvania. Limestone desports in the marine zones represent times when ancient seas covered the land and deposited rocks. Limestone forms in clear, warm, shallow marine waters. The resulting layers read like a story.

The Ames Limestone caps the top of the formation. In-between, you will find Woods Run Cambridge, Pine Creek, and Brush Creek Limestone. The bottom of the formation is the Upper Freeport Coal layer. Unfortunately, several older research papers referenced the Pine Creek Limestone as the Upper Brush Creek. This designation is also popular in Ohio. Unfortunately, it isn’t apparent to correlate limestone layers between Pennsylvania and our neighbors.

Fossils in the Glenshaw Formation

The Glenshaw in Pennsylvania represents a very dynamic period of sediment deposits. Dynamic deposits generate an extensive range of fossils; the rarest are tetrapods. Most vertebrate fossils are primarily found in thin, nonmarine limestones or paleosols. A college student at the time, Adam Striegel, discovered the carnivorous tetrapod Fedexia striegeli in the younger Casselman Formation. In more detail, the paper describing this rare find also contains vertebrate discoveries within the Conemaugh Group.

With this wide range of available fossils, there are many types to find. Land vertebrates (extremely rare), fish, plants, and a wide gamut of marine creatures are available to see.

Plant Fossils Available

Thus far, I have found many plant fossils between the Woods Run and Brush Creek Limestone. Within, there are various shale and sandstone layers. Plants found locally in the Glenshaw Formation include Calamites, Lepidodendron, Macroneuropteris, and the seed fern Pecopteris.

Marine Fossils Available

Along with plant fossils, marine fossils have been plentiful in my part of the Glenshaw. One can find these fossils in both limestone, shale, and sandstone. Although, so far, I have only found plant fossils in sandstone. Examples include Gastropods, Cephalopods, Brachiopods, Crinoids, Clams, Sea Pens, and even a Fish/Shark Tooth.

Particular layers of the Brush and Pine Creek limestones appear to preserve shell material with original aragonite material.

Geologic Time

This formation represents 5 million years, according to a Ph.D. dissertation by Shulik in 1979. Additionally, according to Perera and Stigall in 2018, figure 2 of their research shows the Glenshaw deposits starting at 307 million years ago and ending at 303.7 million years ago. These newer estimates place this closer to 3.3 million years.

Larger Picture of the Glenshaw

All of the rocks within the Glenshaw Formation are sedimentary rocks. There may be an ash fall layer, still part of the sediment, sitting below the Pine Creek limestone. In literature about the formation, there exist several charts that correlate the various layers with geologic time. This illustration below is a compromise between charts by J.A. Harper and S. N. Perera.

Gallery of Rocks from the Glenshaw Formation

Split Shale

Showing Coloration in Shale

Shale

Sandstone with Underlying Shale

References and Further Reading

- Article – Wikipedia

- Formation Page – USGS

- Flint, N.K., 1965, Geology and mineral resources of southern Somerset County, Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Geological Survey County Report, 4th series, no. 56A, 267 p.

- Heckel, P.H., Barrick, J.E., and Rosscoe, S.J., 2011, Conodont-based correlation of marine units in lower Conemaugh Group (Late Pennsylvanian) in Northern Appalachian Basin, Stratigraphy, v. 8, p. 253-269.

- Lebold, J.G., 2005, Gradient and recurrence analyses of four marine zones in the Glenshaw Formation (Upper Pennsylvanian, Appalachian Basin), West Virginia University Dissertation

- Shulik, S.J., 1979, The Paleomagnetism of the Carboniferous Strata in the Northern Appalachian Basin with applications toward magnetostratigraphy

- S.N. Perera, A.L. Stigall, Identifying hierarchical spatial patterns within paleocommunities: An example from the Upper Pennsylvanian Ames Limestone of the Appalachian Basin – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology V. 506, Pages 1-11

- D.S. Berman, A.C. Henrici, D.K. Brezinski, A.D. Kollar, 2010, A New Trematopid Amphibian (Temnospondyli: Dissorophoidea) from the Upper Pennsylvanian of Western Pennsylvania: Earliest Record of Terrestrial Vertebrates Responding to a Warmer, Drier Climate – Annals of Carnegie Museum Vol 78, No 4.