Class: Cephalopoda Cuvier, 1797

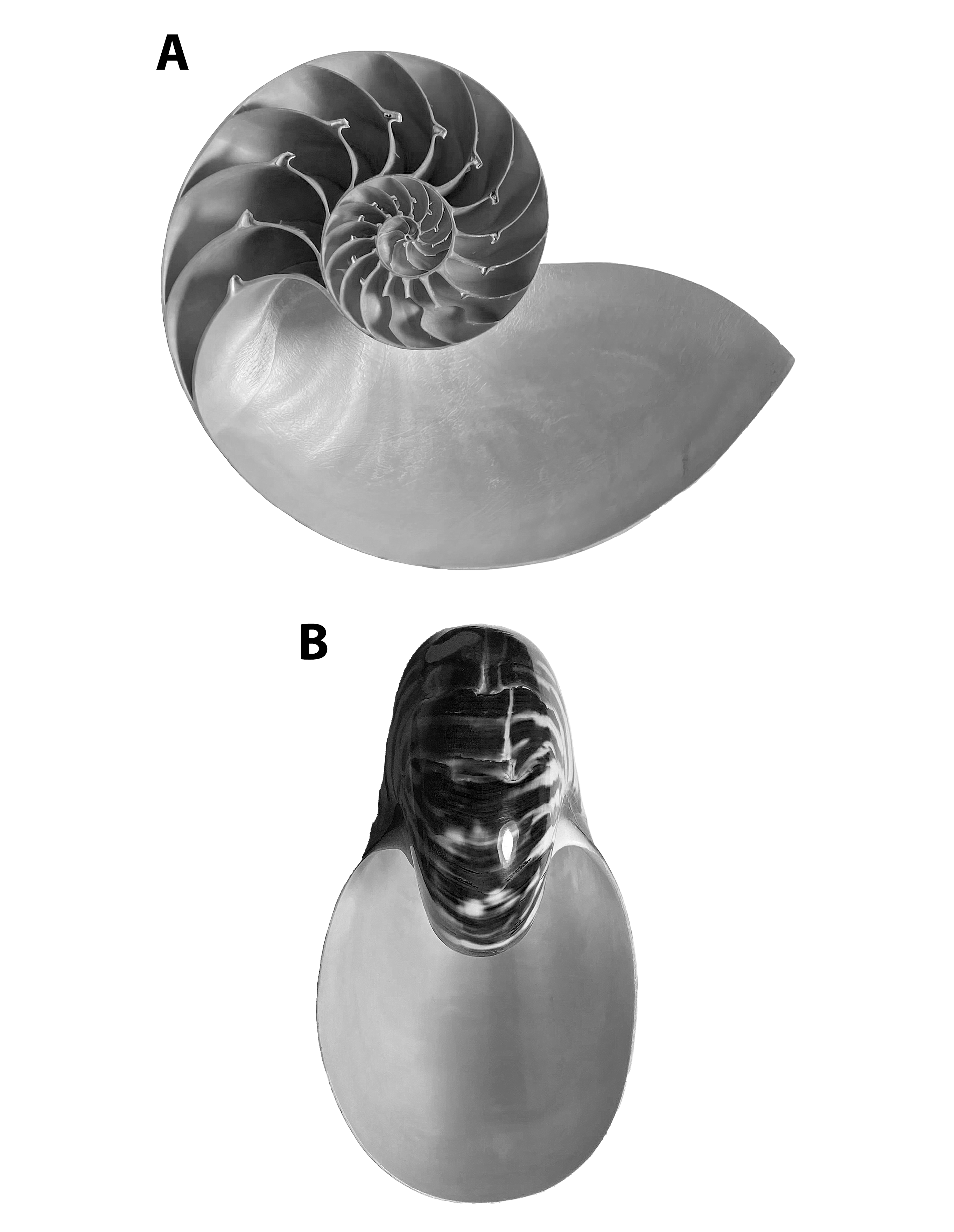

Cephalopod lineages go back to the Cambrian age, over 500 million years ago. Of the orders available in Armstrong County, Late Pennsylvanian surface rocks, the uncoiled-shelled groups Orthocerids and Oncocerids first appear in the Ordovician, and the coiled-shelled Nautilids and Goniatids both arrive in the Devonian. Only the Nautilida survived until the modern day and make up the only two genera of living external-shelled cephalopods, Nautilus and Allonautilus. All other living cephalopods have evolved to internalize or remove the shell.

This complicates the study of many fossil cephalopods because the nature of how they lived cannot be directly studied today. Both the orthocerids and oncocerids had uncoiled shells. As the Devonian gave rise to more fish, these shell plans likely made them easier to prey upon. The Nautilids and Goniatids both had coiled shells, which provided some protection against the thriving fish. By the Late Pennsylvanian period, the Oncocerids were nearly extinct. The Oncocerid Poterioceras curtum is the sole representative of the bedrock studied in this book.

The straight and narrow cone-shaped Orthocerids lasted into the Mesozoic. The sole representative of the group in the Glenshaw Formation in Armstrong County is Pseudorthoceras knoxense. Kröger and Mapes (2005) called this species “the characteristic orthocerid of the Carboniferous in general”.

Cephalopods found in Late-Pennsylvanian Rocks of Armstrong County

There are many representatives of coiled-shelled cephalopods in the Brush Creek and Pine Creek limestone, both in sheer numbers and in diversity. One can easily find Metacoceras, Solenochilus, Domotoceras, Liroceras, and Schistoceras. Some collected Solenochilus may be Ephippioceras. Miller and Unklesbay (1942) reported on all the aforementioned genera along with Megaglossoceras, Pennoceras, and Eoasianites from the Brush Creek limestone in Western Pennsylvania. Tainoceras appears in the Glenshaw Formation but only in the younger Ames Limestone.

Most rare are cephalopod aptychus, which Harper (1989) recovered (deposited in the Carnegie Museum as CM-35509) and reported from the Ames Limestone in neighboring Allegheny County, PA. The find is only 14 miles from the Parks Township Brush Creek locality. His was the first reported from Pennsylvanian surface rocks over the Appalachian Basin.

Cephalopod beaks first appear in the fossil record during the Devonian period of increased competition with fish. One theory states that many animals evolved defense mechanisms from the fish, and the cephalopods also evolved a beak to keep pace with the fish. Mapes (1987) reported on the occurrence of upper Paleozoic cephalopod mandibles and noted that occurrence in Nautiloid-dominated locations (such as our study area) was very rare. These beaks consisted of chitin, a material not enduring burial like calcitic shells. They also have a similar appearance to bivalves and can be mistaken for one when found.

Goniatites have a more complex suture compared to the simple ones of Nautiloids. The Goniatids, such as Schistoceras and Pennoceras, are rare compared to the Nautiloids, but only in the Appalachian Basin. In the midcontinent, their numbers increase greatly in comparison. This is due to a different paleoenvironment, where limestone deposits in western Pennsylvania surface rocks result from many inundating but temporary (on a geological scale) floods of the local basin with seawater. These shallow seas were likely dominated by Nautiloids, with only the occasional Goniatid populating the area. In the mid-continent basin, Goniatid populations are much higher.

Over time, into the Mesozoic, ammonoids like Goniatites evolved more complex sutures. Taxonomists divide Ammonoid sutures into three distinct groups: Goniatites, Ceratites, and Ammonites. All three have sutures with peaks and valleys, known as saddles and lobes. The goniatites have a zig-zag suture, with each saddle and lobe ending in a simple point. The Ceratitids evolved in the late Permian and had subdivided lobes.

Last, the ammonites (often confused with ammonoids, the name of all three groups) have subdivided saddles and lobes. While it is not known why these three types evolved, it is generally accepted that they helped to allow the creatures to hunt in deeper waters and to help protect them if preyed upon. The complex sutures helped reduce the distance between each suture line, increasing strength against the water pressure of deeper seas. This reduced surface area for each camerae could also allow enough strength to stop a predator bite or save it from a fatal shell wall break.

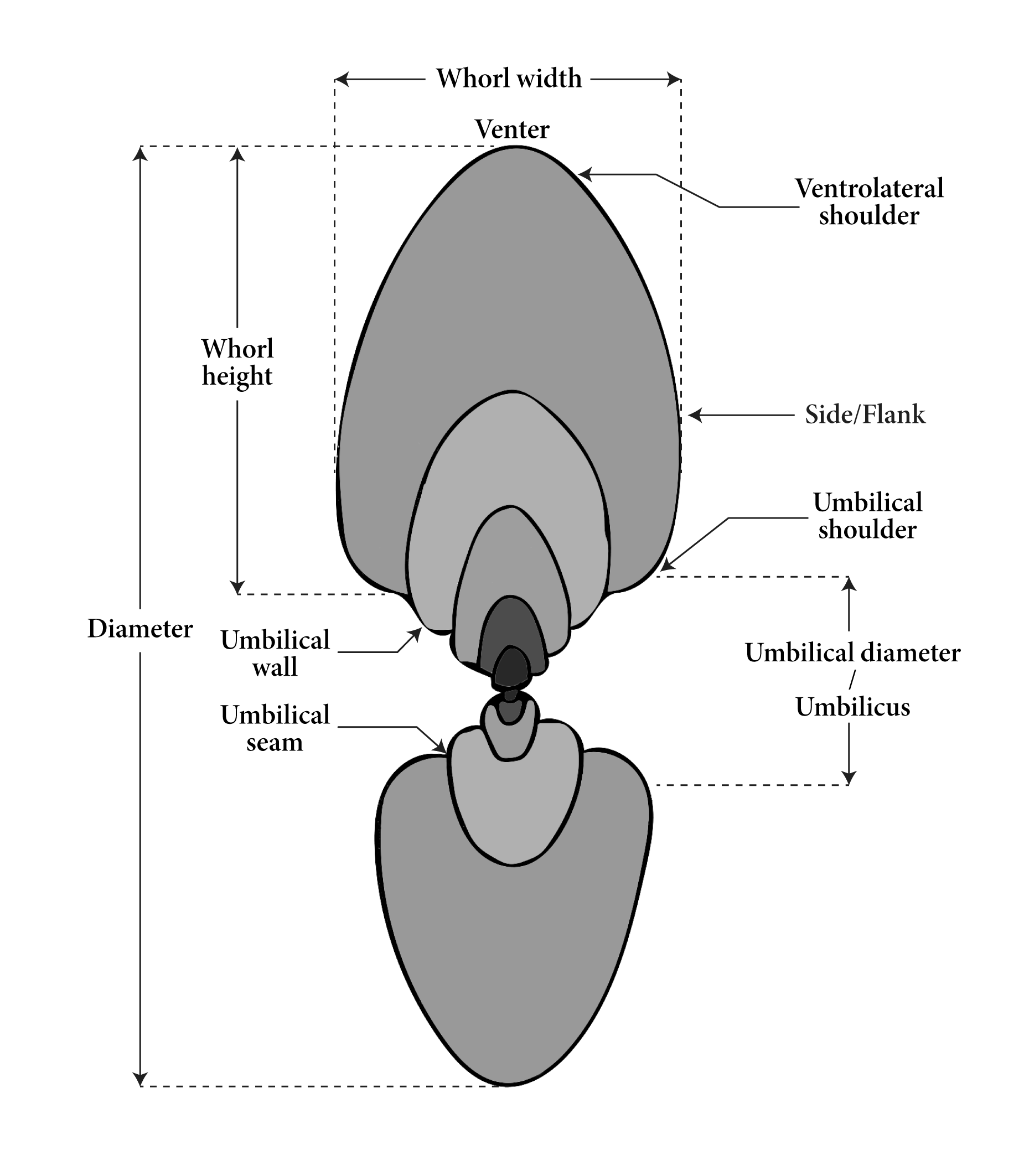

Cephalopod Shell Morphology

More Information

Late Carboniferous Fossils from the Glenshaw Formation in Armstrong County, Pennsylvania

Preface | The Photographic Process

Localities: Locality SL 6445 Brush Creek limestone | Locality SL 6533 Pine Creek limestone

Bivalvia: Allopinna | Parallelodon | Septimyalina

Cephalopoda: Metacoceras | Poterioceras | Pseudorthoceras | Solenochilus

Gastropoda: Amphiscapha | Bellerophon | Cymatospira | Euphemites | Glabrocingulum | Meekospira | Orthonychia | Patellilabia | Pharkidonotus | Retispira | Shansiella | Strobeus | Trepospira | Worthenia

Brachiopoda: Cancrinella | Composita | Isogramma | Linoproductus | Neospirifer | Parajuresania | Pulchratia