Class: Gastropoda Cuvier, 1795

Distribution and diversity

Gastropods have conquered the Earth. You’ll find them on land and in both salt and freshwater. Compared to the other classes of Mollusca, bivalves only live in water, and cephalopods can only tolerate salt water (marine). Within the phylum Mollusca, gastropods have more than three times as many described species as the second-place group, Bivalvia. They are recognizable to humans with whom they coexist on land. However, the group exhibits its most remarkable diversity in marine environments.

Long history and adaptive success

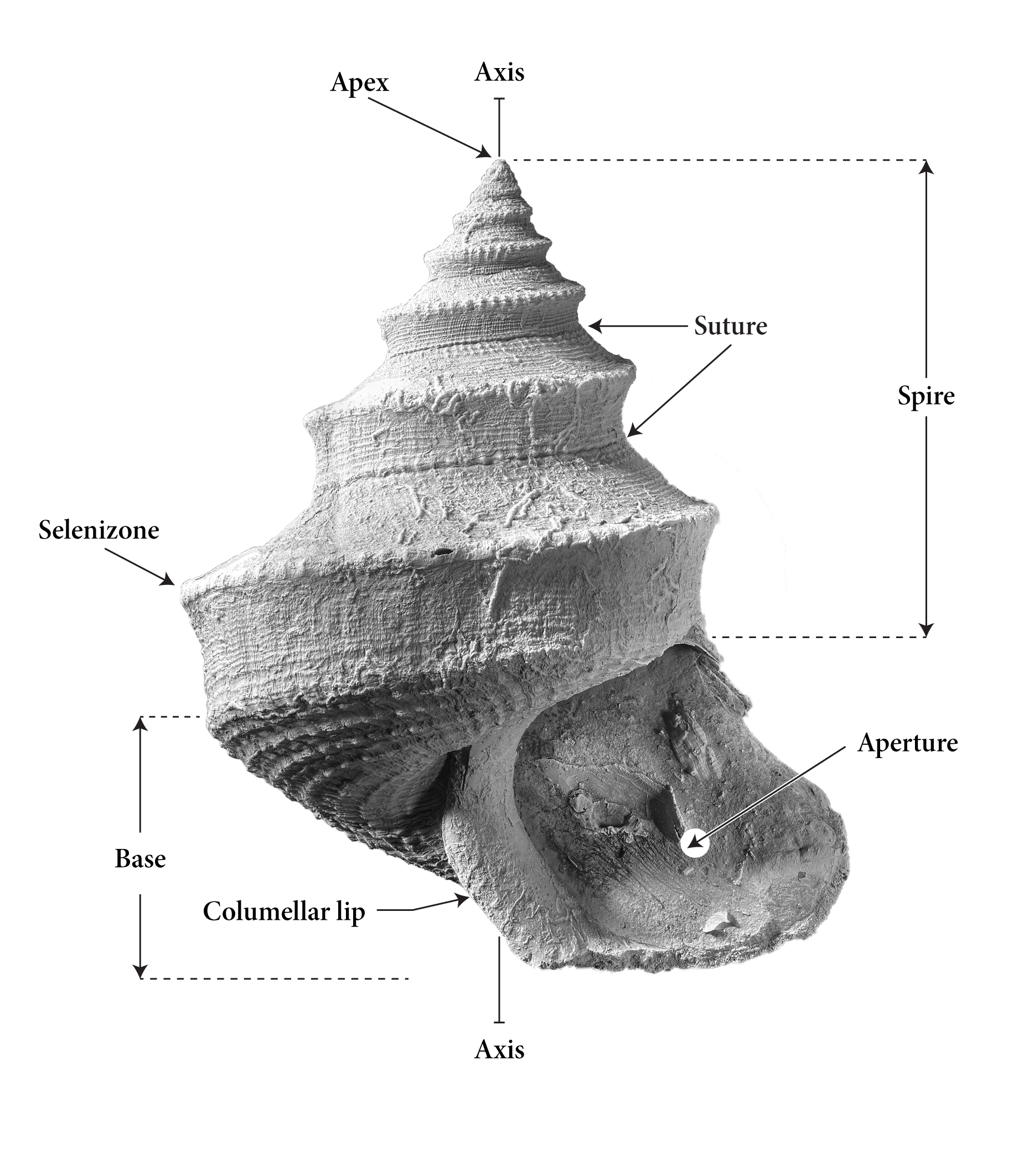

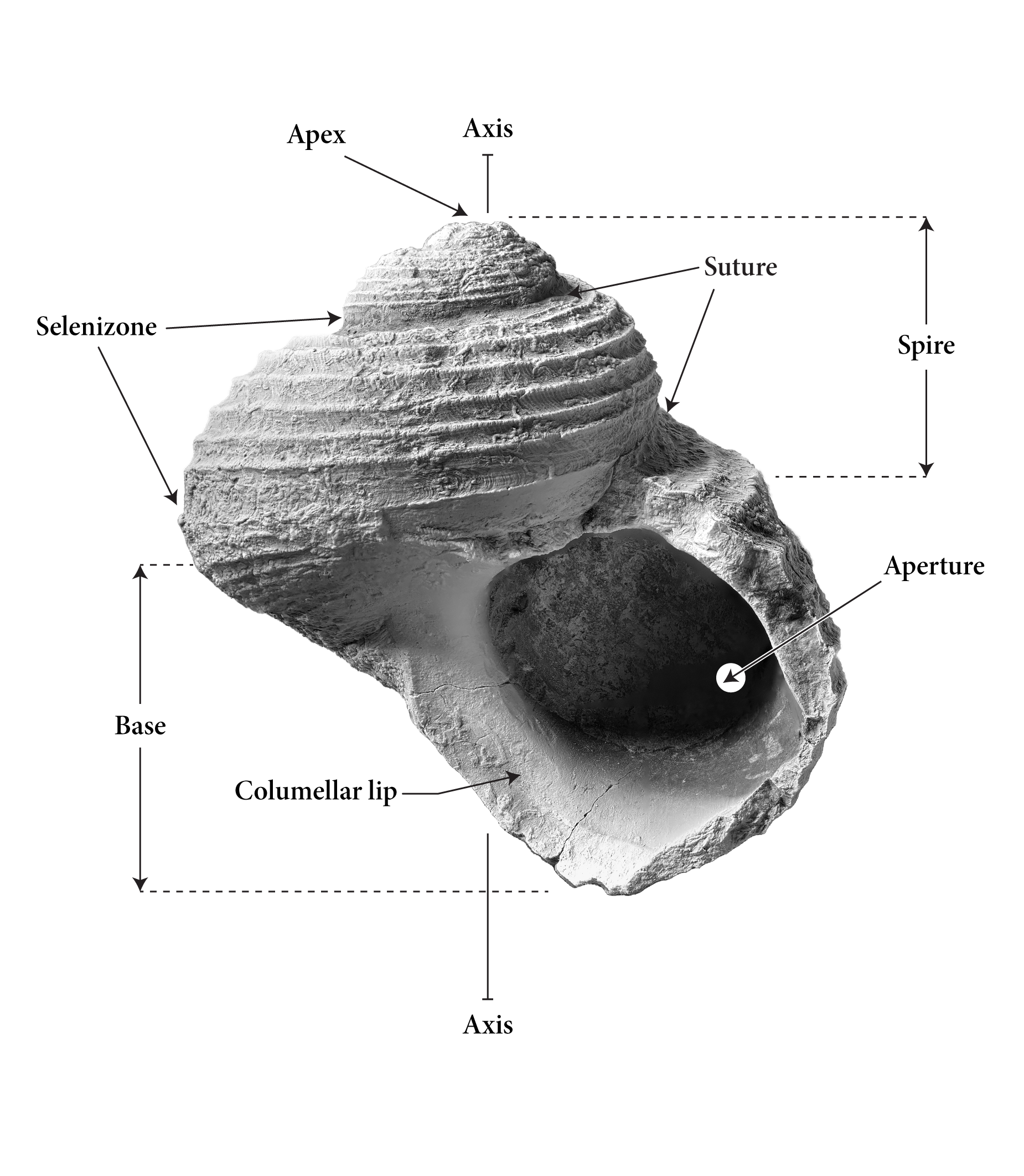

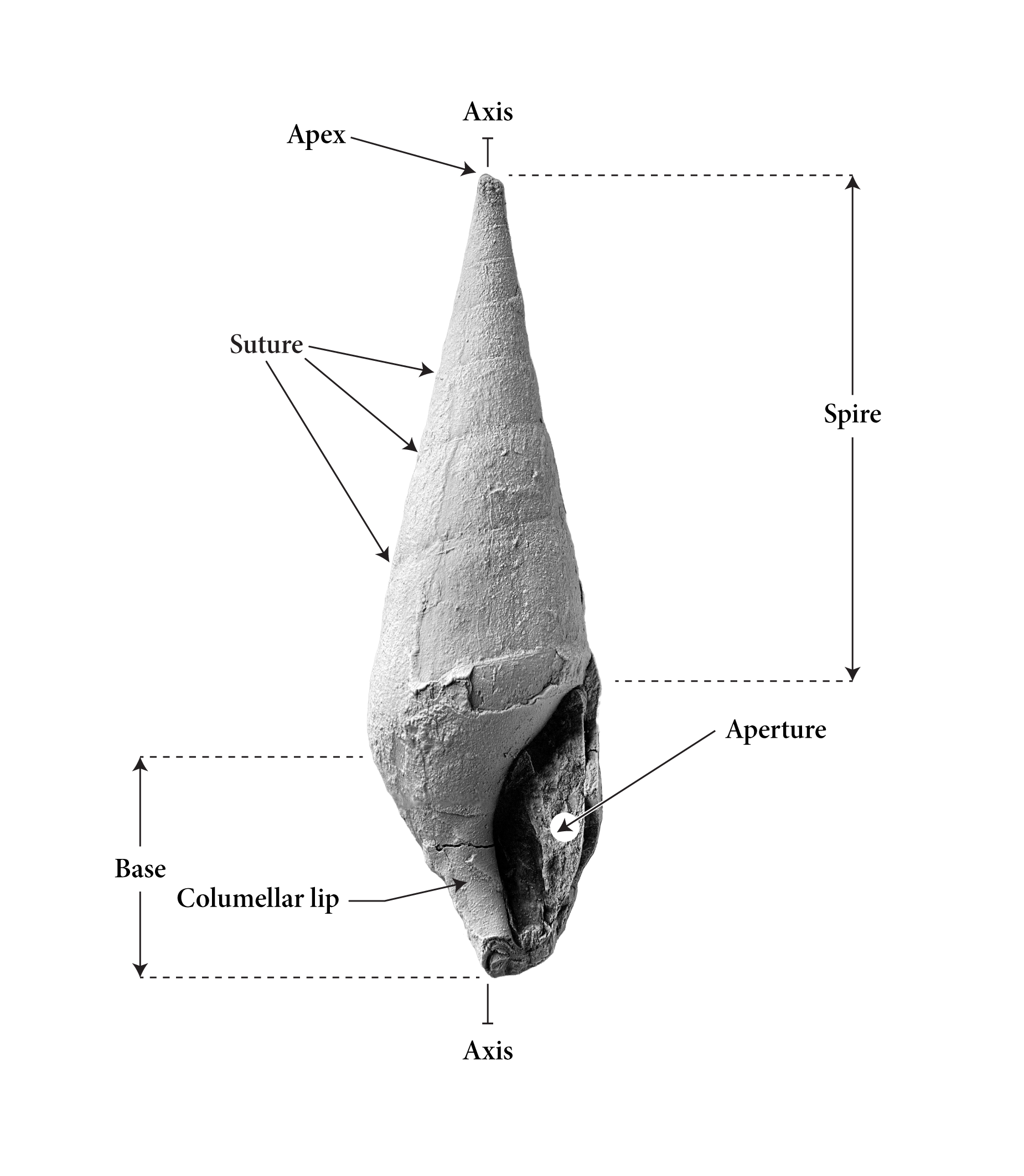

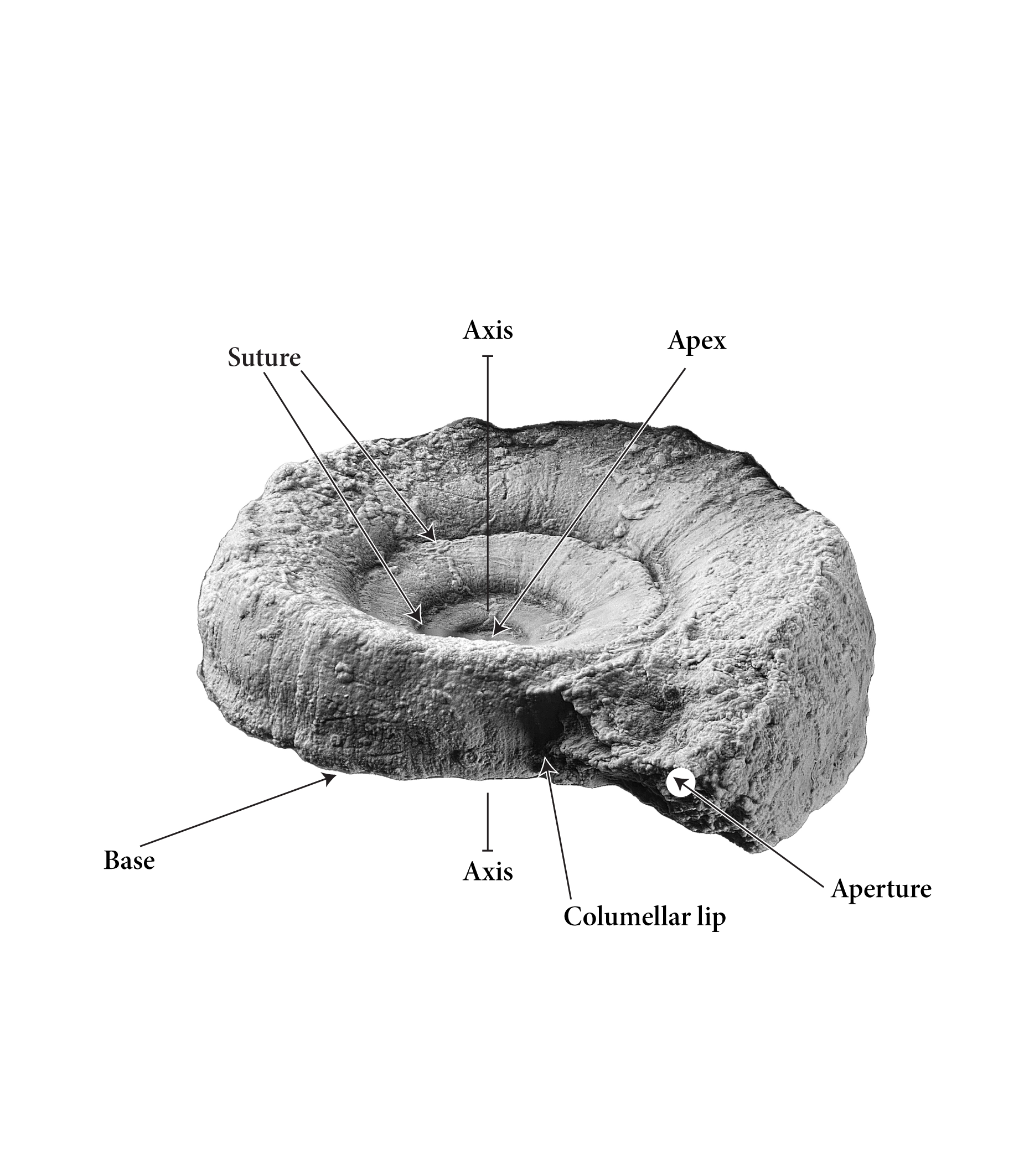

Despite existing for over 500 million years, surviving several mass-extinction events, and the evolution of numerous predators, including their relatives, gastropod diversity has only steadily increased since the first gastropod evolved. Class members are usually recognizable by their shells, which vary in form and provide protection for most species. For some species, a covering called the operculum helps to close the shell opening (the aperture) to provide extra protection. Some groups have shells too tiny to retract into, internalized shells, or none.

The fossil record and how shells form

We know most fossil gastropods from their fossilized calcium carbonate shells. Authors can infer details about the living tissues of extinct groups, but only by using clues such as muscle scars and shell morphology. In shelled mollusks, the mantle secretes calcium carbonate as the creature grows. Shell shape, size, and ornament are all due to periodic fluctuations and variations at the mantle edge.

Taxonomy in this book

The two localities in this book have fossils from seven orders of Gastropoda. Unfortunately, precise taxonomic naming is difficult because Gastropod taxonomy is constantly revised, and many unranked groups exist. Modern workers can use DNA to build and separate groups, a privilege not afforded to the 305-million-year-old fossils found here. Furthermore, many workers (references here) have attempted to use the protoconch (the first part of a shell to develop at birth) to help determine groups. This practice has yet to be universally accepted.

Revisions and instability in classification

Chaos within the ranked hierarchy disrupts the classic Linnaean taxonomy in several cases. For example, Meekospira lacks a taxonomic order. In addition, the turreted Worthenia shares characteristics with members of the Phymatopleuridae but, for a long time, has been classified within the Lophospiridae. Karapunar et al. changed this condition in 2022, the same year the writing and research for this book commenced. For several decades, authors have revised or called into question much of the precedent established in the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology.

Major subclasses represented

The gastropods in this study belong to four major subclasses. Simroth (1906) erected Amphigastropoda as a home for the Bellerophontoidea. Their placement has long been debated, particularly over whether bellerophontids represent true gastropods. Most authors now accept that they are, though not unanimously.

Vetigastropoda

When Salvini-Plawen named Vetigastropoda in 1980, he intended it to include Pleurotomarioidea and other superfamilies. Subsequent debate has complicated the placement of several groups, yet most workers agree that members of Pleurotomariida belong within this clade (treated by different authors as either a clade or subclass). Extant representatives are marine, possess a nacreous shell layer, and some exhibit a selenizone.

Neritimorpha

Locally identified Neritimorpha include only Orthonychia. Raymond (1911) reported Naticopsis from the Vanport Limestone of the older Allegheny Group, but none from the Glenshaw Formation.

Caenogastropoda

The Caenogastropoda includes gastropods that underwent torsion and have a single pair of gill leaflets. Most members live in saltwater, but some inhabit freshwater and dry land. Interestingly, all members lack a nacreous layer (as in Shansiella). Although the subclass contains the majority of living gastropods, it accounts for less than half of the genera found in the Glenshaw Formation in Armstrong County. Hence, other orders, such as Pleurotomariida and Bellerophontida, overshadowed the diversity in the Caenogastropoda during the Carboniferous.

Convergent Evolution

One interesting aspect of gastropods is observable convergent evolution. Similar features may repeatedly evolve as new species (and higher taxa) emerge. For example, the Silurian-Devonian Australonema and the Carboniferous Shansiella look nearly identical at first glance. They both have the same coiling and a spiral ornament over the shell. Yet, upon closer inspection, you’ll find that Shansiella has a selenizone. The modern Turbo also shares characteristics with the pair, which is why Conrad (1835) named Turbo insectus (See The Curious Case of Turbo insectus).

Classification hierarchy for all identified gastropods from the Brush Creek and Pine Creek limestone.

- Subclass Amphigastropoda Simroth, 1906

- Order Bellerophontida McCoy, 1852

- Superfamily Bellerophontoidea McCoy, 1852

- Family Euphemitidae Knight, 1956

- Family Bellerophontidae McCoy, 1852

- Superfamily Bellerophontoidea McCoy, 1852

- Order Bellerophontida McCoy, 1852

- Subclass incertae

- Order Euomphalida de Koninck 1881

- Superfamily Euomphaloidea White 1877

- Family Euomphaidae White 1877

- Superfamily Euomphaloidea White 1877

- Order Euomphalida de Koninck 1881

- Subclass Vetigastropoda Salvini-Plawen1980

- Order Pleurotomariida Cox & Knight 1960

- Superfamily Eotomarioidea Wenz, 1938

- Family Eotomariidae Wenz, 1938

- Family Gosseletinidae Wenz 1938

- Superfamily Pleurotomarioidea Swainson, 1840

- Family Portlockiellidae Batten, 1956

- Family Phymatopleuridae Batten 1956

- Superfamily Eotomarioidea Wenz, 1938

- Order Pleurotomariida Cox & Knight 1960

- Subclass Neritimorpha Golikov and Starobogatov 1975

- Order incertae

- Superfamily Platyceratoidea

- Family Platyceratidae

- Superfamily Platyceratoidea

- Order incertae

- Subclass Caenogastropoda

- Order (or Cohort) Sorbeoconcha Ponder and Lindberg 1997

- Order incertae

- Superfamily Subulitoidea

- Family Subulitidae Lindström 1884

- Superfamily Soleniscoidea Knight 1931

- Family Soleniscidae Knight 1931

- Family Meekospiridae Knight 1956

- Superfamily Subulitoidea

Shell Morphology for various gastropods found in Armstrong County

Gastropoda Menu

- Amphiscapha

- Bellerophon

- Cymatospira

- Euphemites

- Glabrocingulum

- Meekospira

- Orthonychia

- Patellilabia

- Pharkidonotus

- Retispira

- Shansiella

- Strobeus

- Trepospira

- Worthenia

References

- Meek, F. B., and Worthen, A. H., 1860. Description of new Carboniferous fossils from Illinois and other western states. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 12:447–472

- Moore, R. C., 1941. Upper Pennsylvanian gastropods from Kansas: Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin 38, pt. 4, p. 121–164, 3 pls., 7 figs.

- Norwood, J. G., and Pratten, H., 1855. Notice of fossils from the Carboniferous Series of the western states belonging to the genera Spirifer, Bellerophon, Pleurotomaria, Macrocheilus, Natica, and Loxonema, with descriptions of eight new characteristic species. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 3: p. 71–77

- Yin, T. H., 1932. Gastropoda of the Penchi and Taiyuan Series of North China, Palaeontologica Sinica, Series B.

Late Carboniferous Fossils from the Glenshaw Formation in Armstrong County, Pennsylvania

Preface | The Photographic Process

Localities: Locality SL 6445 Brush Creek limestone | Locality SL 6533 Pine Creek limestone

Bivalvia: Allopinna | Parallelodon | Septimyalina

Cephalopoda: Metacoceras | Poterioceras | Pseudorthoceras | Solenochilus

Gastropoda: Amphiscapha | Bellerophon | Cymatospira | Euphemites | Glabrocingulum | Meekospira | Orthonychia | Patellilabia | Pharkidonotus | Retispira | Shansiella | Strobeus | Trepospira | Worthenia

Brachiopoda: Cancrinella | Composita | Isogramma | Linoproductus | Neospirifer | Parajuresania | Pulchratia