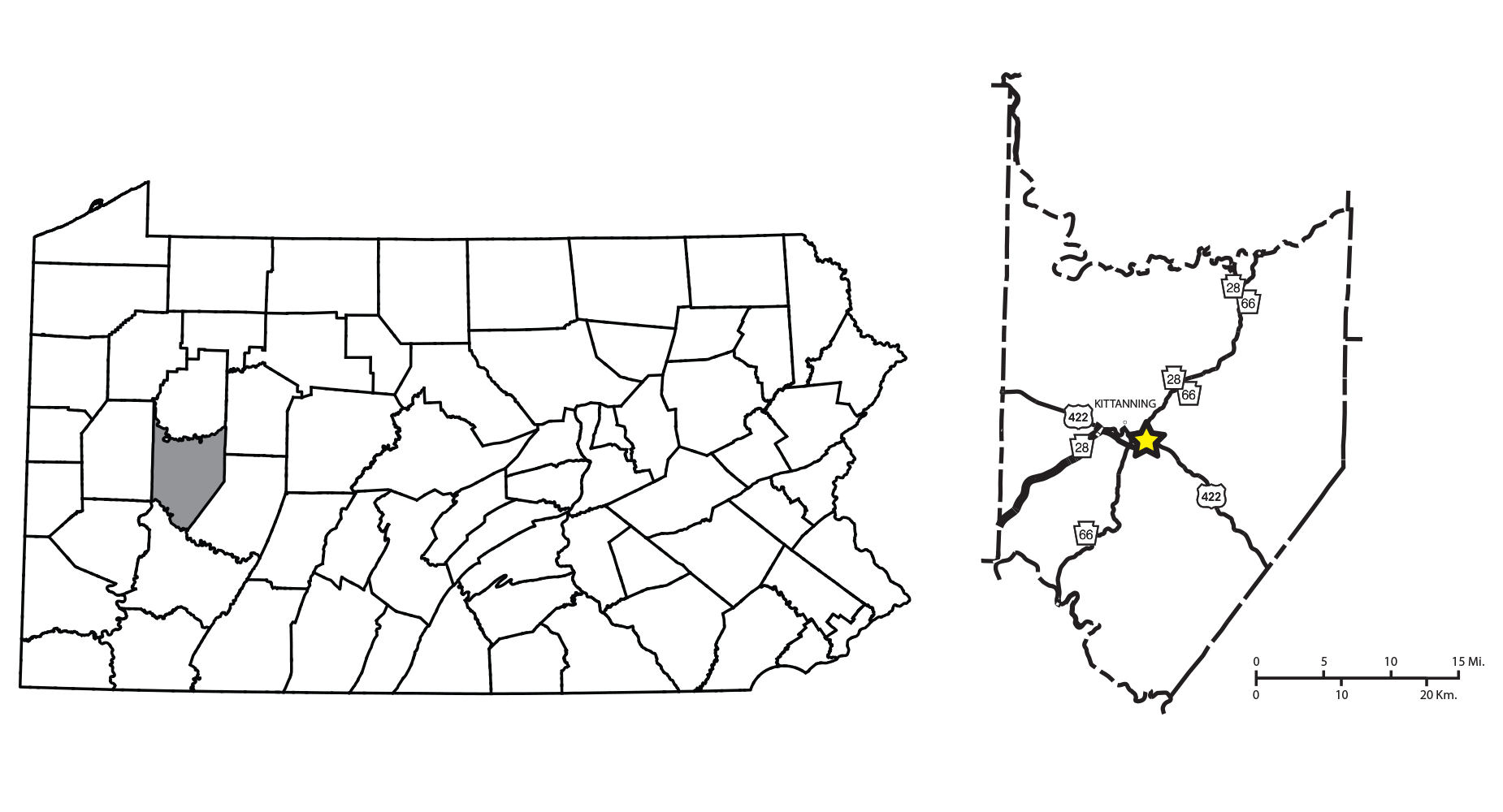

Carnegie Museum stratigraphic locality SL 6445 sits in northern Manor Township, central Armstrong County, at a pair of highway on and off-ramps at the intersection of PA 28/66 and U.S. 422. PA 28/66 itself cut through hills in the terrain, and in this particular location, workers made deep cuts into the bedrock to clear room for the ramps. The Pine Creek limestone here is a foot thick (30.5 cm) on average but can run thinner or thicker. In the underlying bedrock, you can also see gradual dips and rises due to regional folding—synclines and anticlines.

The limestone is dark gray and fossiliferous. It is argillaceous (silt-sized particles) and arenaceous (sand-sized particles). In other locations, the Pine Creek limestone has tall mounds extending downwards, measuring ten feet in height. Marine animals could have dug out these curious burrows. However, there appear to be none in Manor Township.

White (1878) named the limestone from a rock exposure on a hill between Pine Creek and Gourdhead Run in Hampton township, Allegheny County. Later, Stevenson (1906) correlated the Pine Creek limestone with the Cambridge Limestone in nearby Ohio. With five years of seniority over the Pine Creek limestone, the name Cambridge Limestone came into use in West Virginia and Ohio. It also replaced Pine Creek in some Pennsylvania literature.

It wasn’t until 1984 that Busch correlated the Cambridge Limestone with the Nadine Limestone in Pennsylvania, thus reintroducing the Pine Creek limestone as the correct name for the stratum. Further work with fossil condonts (Heckel, Barrick, and Rosscoe 2011) solidified these findings and helped correlate the Pine Creek limestone with other limestones in the mid-continental United States.

The Paleoenvironment

The Pine Creek limestone and the older Brush Creek limestone are dark-colored rocks. At each site, many white fossilized marine shells exist. These white shells are usually primary aragonite or high-magnesium calcite, the original mineral of many marine shells. Not all marine shells are made of this form of calcium carbonate, as many build their shells using the most stable form, calcite.

The ancient seawater appears very anoxic with this combination of well-preserved shell minerals and dark limestone. Seawater anoxia can occur in a few different ways. One is due to an overload of the organic matter in the sediment. As bacteria break down matter, they consume oxygen and release carbon dioxide. Still water is another cause, which would prevent more oxygen from absorbing into the water.

The sea waters that laid the Pine Creek limestone resulted from changing paleoclimate, where warmer average air temperatures melted the locked-up ice in the Southern Hemisphere. Melting ice adds water to global seas and raises global sea levels. Sea level changes occurred several times during the Late Pennsylvanian period, resulting in many narrow marine limestone strata throughout the Glenshaw Formation.

Below the equator, today’s Western Pennsylvania lay east of the still-building Allegheny Mountains during the Carboniferous. As these mountains eroded, they pushed large amounts of sediment into a floodplain. During colder global temperatures, the waters receded, and large deposits of silt and sand-sized sediment flooded the basin. Then, tens to hundreds of thousands of years later, global temperatures would rise and, in turn, cause seas to rise once again. This repeating event-cycle associated with global sea-level change is an allocyclic event.

The paleoclimate of a sea with anoxic water affects fossil recovery at SL 6445. Most of the recovered fauna here have their shells included. Many are still composed of unconverted aragonite. Depending on the shell shape, size, and thickness, some or all of the shell is recoverable. In areas where these conditions don’t exist, the original shell often dissolves away, leaving only the steinkern, a sediment rendering of the empty spaces in the shells.

While the Pine Creek and Brush Creek localities preserve shells similarly, the Pine Creek limestone at Manor Township is much more fissile than its Brush Creek counterpart. They both have a similar thickness, but the Pine Creek limestone is lighter in color. The Brush Creek is darker and more brittle. These physical properties are due to a higher calcite content in the rock. Fossils in the Pine Creek limestone release quickly, and the outsides of shells often do not adhere to the stone. In contrast, the adhesion of the outer shell to the limestone of fossils in the Brush Creek limestone is quite strong.

The Pine Creek limestone has dark calcitic shales above and below it. Ironstone nodules appear throughout, with larger nodules higher above the limestone proper. In the first meter of shale above the limestone, I find the gastropods Meekospira and Pharkidonotus. Specimens from this zone have greater detail but are fragile, with lower calcium carbonate content than limestone.

The Paleobiology

The distinct zones within the Pine Creek limestone represent a few different periods of sediment deposition. The topmost calcitic shale features numerous horn corals, the gastropod Meekospira peracuta and Pharkidonotus percarinatus. Several more species of gastropods are common, including Strobeus, Shansiella, and Amphiscapha, to name a few. Cephalopods also appear here. Crinoid pieces are here but rare.

Small limestone mounds appear frequently throughout this top layer. In dissection, they can contain fossils or not and often contain swirling pyrite deposits. I’ve observed plant matter within the Glenshaw Formation at both locations frequently replaced with pyrite; this raises the question of whether these nodules contained plant matter. Large pure limestone lenses also appear in the lower limestone.

Below the shale is a less fissile massive deposit, approximately six inches (15.2 cm) in height on average. Large Metacoceras, gastropods, unidentified bivalves, and the brachiopod Antiquatonia portlockiana appear here. Shansiella carbonaria and species of Strobeus are here and typically warped and massive. Occasional large teeth of Petalodus ohioensis appear here more often than the other layers.

Diversity starts to drop in the bottom layers. A 1.5-inch (3.8 cm) fissile limey shale separates the massive upper limestone deposit from the base limestone. The floor limestone features the lowest population of marine fossils and is the least sought after while collecting.

References

- Betts, W. W. (2012). Rank and gravity, the life of General John Armstrong of Carlisle. Heritage Books.

- Busch, R. M., Brezinski, D. K., 1984, “Stratigraphic analysis of Carboniferous Rocks in Southwestern Pennsylvania Using A Hierarchy of Transgressive-Regressive Units, Eastern Section Meeting of American Association of Petroleum Geologists, p. 28, 30.

- Harper, J. A., 2016, Some geological considerations of the marine rocks of the Glenshaw Formation (Upper Pennsylvanian, Conemaugh Group), in Anthony, R., ed., Energy and environments: Geology in the “Nether World” of Indiana County, Pennsylvania. Guidebook, 81st Annual Field Conference of Pennsylvania Geologists, Indiana, PA, p. 47–62.

- Harper, J. A., Bragonier, B., 2016, Pine Creek Marine Zone, US 422 Bypass, Kittanning, in Anthony, R., ed., Energy and environments: Geology in the “Nether World” of Indiana County, Pennsylvania. Guidebook, 81st Annual Field Conference of Pennsylvania Geologists, Indiana, PA, p. 63–74.

- Heckel, P. H., Barrick, J.E., and Rosscoe, S.J., 2011, Conodont-based correlation of marine units in lower Conemaugh Group (Late Pennsylvanian) in Northern Appalachian Basin, Stratigraphy, v. 8, p. 253–269.

- Hughes, H. H, 1933, No. 36 Freeport Quadrangle, Topographical and Geologic Atlas of Pennsylvania

Late Carboniferous Fossils from the Glenshaw Formation in Armstrong County, Pennsylvania

Preface | The Photographic Process

Localities: Locality SL 6445 Brush Creek limestone | Locality SL 6533 Pine Creek limestone

Bivalvia: Allopinna | Parallelodon | Septimyalina

Cephalopoda: Metacoceras | Poterioceras | Pseudorthoceras | Solenochilus

Gastropoda: Amphiscapha | Bellerophon | Cymatospira | Euphemites | Glabrocingulum | Meekospira | Orthonychia | Patellilabia | Pharkidonotus | Retispira | Shansiella | Strobeus | Trepospira | Worthenia

Brachiopoda: Cancrinella | Composita | Isogramma | Linoproductus | Neospirifer | Parajuresania | Pulchratia