Update on Meekopinna

In August of 2024, Tom Yancey named Allopinna godleskya, a new genus and species of pinnid. This article is outdated in terms of the name Meekopinna. A new article describing the find is here: Allopinna godleskya. The article below helped Tom connect with me to study these fossils. Pinnids were poorly covered in North America. Yancey’s work has dramatically increased the diversity of information about these vertically positioned large bivalves that are still alive today, represented by modern species.

—Clint September 2024

###

A note about the status of Aviculopinna

This article will receive several updates over the next month or more. In August of 2022, Yancey et al. published a manuscript on the family Pinnidae with many updates for Aviculopinna. One of the more significant changes was the limitation of the genus Aviculopinna to Permian strata, which excludes any of my specimens from using that name. I tentatively used “Aviculopinna” as a name because my specimens are similar, but I have no substantial evidence that my specimens could use that name. Now that the genus is unavailable, my specimens will use the name “Meekopinna.” My specimens again don’t qualify ultimately for this name; I use it in quotes.

My specimens have features unique to those collected from the Late Pennsylvanian strata of Parks Township. I assembled over one hundred specimens in a few years of collecting. They are often found in life-position and seen easily during limestone-splitting fossil collection work. By closely studying more minor features of these specimens, it may come to light that they are unique. Work is ongoing to make that determination.

One last note is about the usage of Pteronites. The Ohio Publication “Pennsylvanian Marine Bivalvia and Rostroconchia of Ohio” heavily uses Pteronites in the text for pinnids in the publication. This is likely due to the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology (1969) publishing the synonymy, with Pteronites as the senior name. Yancey’s assessment shows that Pteronites is a small genus limited to early Pennsylvanian specimens.

I will be updating the content below in the future.

—Clint August 2002

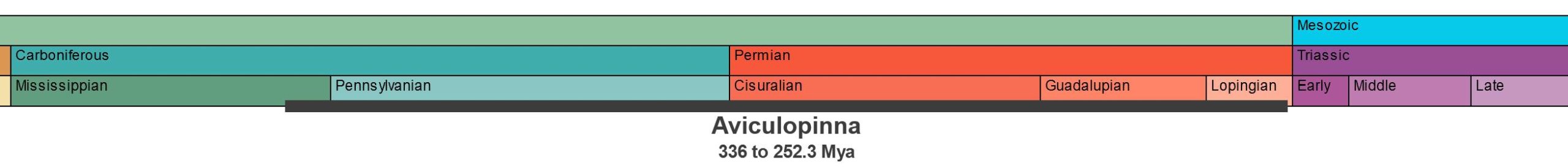

Aviculopinna

336.0 to 252.3 MYA

Scientific Classification

Kingdom:

Animalia

Phylum:

Mollusca

Class:

Bivalvia

Order:

Pteriida

Family:

Pinnidae

Genus:

“Aviculopinna”

Species:

Meek 1864

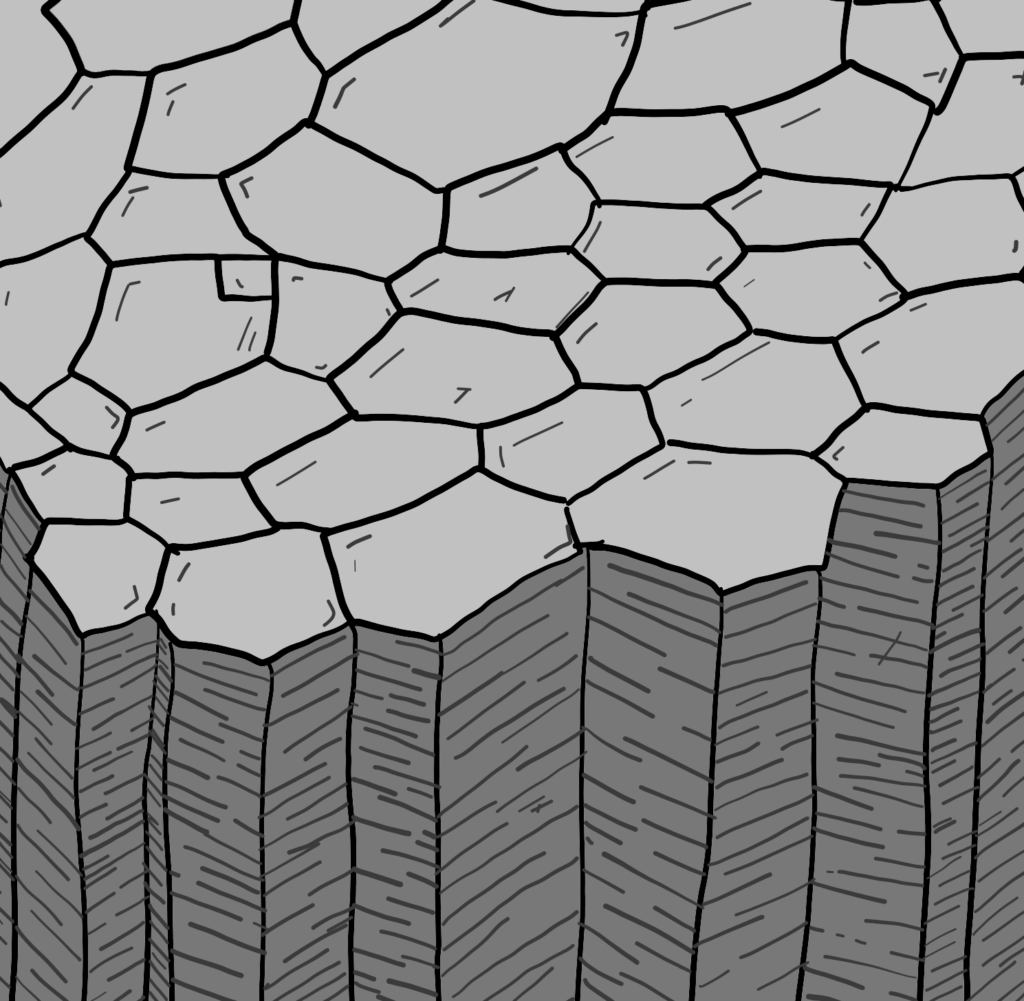

Aviculopinna and Meekopinna are extinct genera of mollusks in the class Bivalvia. All bivalves have two shells. Nearly all have shells that are a mirror image of each other. Bivalves live in both freshwater and seawater. Aviculopinna and Meekopinna are both in the family Pinnidae, consisting of genera with triangular pen-shaped shells. The shell has a prismatic layer made of geometric columns of agronite. These creatures bury and anchor their shells on the seafloor while alive and often become buried in the same position. They can be large in extant genera, with the largest known reaching 120 cm (4 feet) in length.

The specimens I collected were challenging to identify when I first started to find them. They are easy to find, typically presenting as a pointed oval shape on the surface of the local Brush Creek limestone. I have collected well over a hundred specimens in four years, with about a dozen of higher quality or much more complete. I first learned about these using the nickname “sea pen,” as they look like a pen. There are three common Carboniferous genus names that are used locally. I often had to decide between Meekopinna, Aviculopinna, and Pteronites. Using written descriptions, fossil plates, and illustrations, the fossils are difficult to discern.

However, I have determined that Pteronites and Meekopinna are incorrect names for my recovered specimens. The genus Pteronites is not valid for Pinnidae species, and Meekopinna has coarse growth lines. This leaves the genus Aviculopinna, which I tentatively identify my specimens as. Yet, Aviculopinna may soon be unavailable for Pennsylvanian species, but research about this condition is still pending.

How to identify genera within Pinnidae

Determining which Carboniferous pinnid genus is correct involves a series of visual identification exercises. Growth lamellae (growth lines) are one such visual indicator. They can be nearly non-existent, minor, or sharp in the description. Another indicator is how wide the specimen is in cross-section. This may be less reliable due to crushing during the fossilization process. The variation of the triangular shape is another metric used for identification. It ranges from subtriangular to triangular. Some studies record the angle between the dorsal and ventral margins. Nevertheless, identification is difficult due to the number of taxonomic opinions that exist. Luiz Anelli et al. (2006) declared that “Paleozoic Pinnidae are in need of a complete investigation.”

Description of local fossil Pinnids

Specimens are narrow, elongate, and subtriangular in shape. Nearly all appear to be missing the shell’s broad, oval-shaped posterior portion. These parts are not reinforced with more robust shell material and rarely remain after fossilization. These fossils present as a thin, pointed oval in cross-section. The dorsal margin is straight. The two valves form a hinge at this margin. The opposite or ventral side gently slopes wider as you reach the top but is more or less generally straight.

Shell features

Growth lines adorn the shell. Mollusk shells are secreted by the mantle, the dorsal body wall covering the visceral mass. As the shell is secreted, these lines mark outlines of points while the animal grows. In local fossil Pinnids, these lines are parallel to the ventral margin, then turn sharply nearly 90 degrees to cross the shell and end at the dorsal margin. Growth lines are tightly spaced but do vary. Different species show variations of growth line spacing. Sometimes, these growth lines sharply turn towards the posterior before meeting the knurled hinge margin.

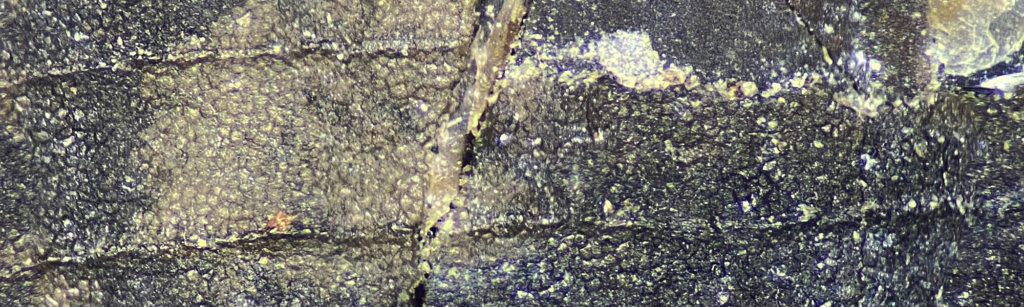

The outside shell surface is made of a prismatic material, which is a feature of living examples of Pinna. The nacreous material inside the shell, mother-of-pearl, is the toughest natural material on earth. The inside shell surface contains most of this material, where you’ll find the visceral mass. Evidence of the prismatic layer can be seen in the photo below. The pitted look is from the crystal surface of the material. Even today, these 300+ million-year-old specimens shimmer in the light.

There are typically two distinct shell layers preserved locally. The topmost is the prismatic layer, which is challenging to recover intact. The inner shell, which is easier to recover, is a recrystallized calcite layer, composed initially of aragonite. You can see this as a pattern resembling frost on a window.

Specimen shells do have occasional apparent crushing. The crushing is primarily visible as micro-fractures in the preserved surface. They are easier to discern using a microscope.

Known life situations of extant pinnid species

Members of the Pinnidae live in a vertical, upright position, with their anterior (pointed) end buried on the seafloor. We know a good deal of information about how these lived because the Pinnidae is still extant. They anchor into the seafloor using byssus threads. Commonly called sea-silk, these threads are collected today and used to make clothing. The posterior and ventral portions of the shell open, allowing seawater to pass through so it can filter feed.

The history of the two genera, Aviculopinna and Meekopinna

To understand how these two genera came into existence, you must go back to the pair of fossil species named by a couple of German paleontologists. First, the earliest of the two named fossil species, Pinna prisca. Count Georg Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm zu Münster described this species of Pinnid in 1839, in a publication Beschreibung einiger seltenen Versteinerungen des Zechsteins. Beiträge zur Petrefacten-Kunde (Translated: Description of some rare fossils of the Zechstein. Contributions to petrefactology). His translated (Google Translate) original description follows.

2) pinna? prisca. Taf. IV. fig. 4., from the copper slate with a blown lead gloss from Merzenberg near Milbitz, not far from Gera. This fossilization, which is most similar to a pinna in its outer shape and stripes, was presented with the previous one by the owner, Mr. Laspe, in the geognostic section of the meeting of naturalists in Jena. Pressure and counter-pressure of this somewhat dubious stone are present. On the sides, stripes go down the length, which are cut through by concentric transverse stripes. The shell is extremely thin. From the same copper slate, Mr. Laspe owns a new species of Palaeoniscus, which will be illustrated and described in the supplement to Prof. Agassiz’s great work on fossil fish.

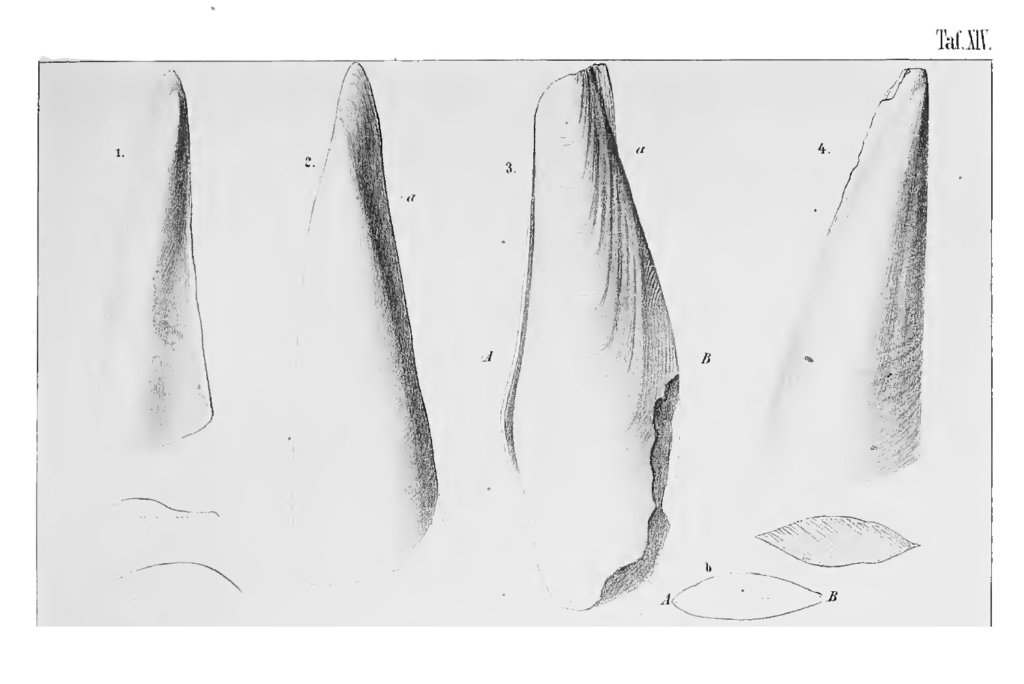

Nine years later, H.B. Geinitz published illustrations of Avicula pinnaeformis in 1848. Geinitz also published in his native language, German. I was able to get the figures and translate the original descriptions of the figures. These illustrations are helpful for genus identification, as F.B. Meek would later use these to create a new genus.

H.B. Geinitz’s Published Figures

The familiar oval shape and general appearance of the shells are apparent here. Below is a translated (using Google Translate) version of the explanation of Table 14 from H.B. Geinitz’s publication.

Explanation of Table XIV.

Fig. 1. Avicula pinnaeformis Gei. – p. 77. Left bowl, an imprint of Gutta-Percha after a copy by Räckingen, Wetterau, in the collection. d. deceased Med.-R. Dr. Speyer in Cassel.

Fig. 2. The same Stone core (steinkern) of the right shell made of dolomitic limestone between Bieblach and Dorna near Gera. (Samil. Pastor Mackroth in Thieschitz.)

Fig. 3. The same right bowl, there, in the same collection, with a transverse section b along the line A – B.

Fig. 4. Lik. left shell from the upper Zechstein von Rückingen, with a cross-section of the same. (Collection of the deceased Med.-R. Dr. Speyer.)

Fielding B. Meek erects Aviculopinna.

In 1864, Sixteen years after Avicula pinnaeformis and twenty-five years after Pinna prisca came into existence, Fielding B. Meek erected a new genus Aviculopinna. He named it during an era when the science of studying shells was known as Conchology. Declaring this new genus, Meek helped include several extinct genera within the Order Pteriida. He erected this genus for Pinnids with narrow elongate shells having regular, sharp growth lamellae, and he set the type to be Pinna prisca (Munster) == Avicula pinnaeformis (Geinitz). Interestingly, he did this in a footnote of his article.

A few years later, in 1867, Meek described A. americana and contrasted it to A. pinnaeformis by stating that A. americana possessed sharp, regular growth lamellae, had no trace of radial striae, and a beak more terminal in position.

Yancey divides Aviculopinna, declaring a new genus, Meekopinna.

In a 1978 publication from the Bulletins of American Paleontology, Volume 74, Number 303, Thomas Yancey declared a new genus, Meekopinna, starting on page 338. He said Aviculopinna americana Meek 1867 was the type for the new genus. Yancey went to great lengths to explain the current status of Aviculopinna. He explained that two common types exist in Carboniferous and Permian rocks. They have either:

- Growth lamellae that are small, sharp, and regular or

- A smooth shell without significant ornamentation.

Despite this significant difference, authors had placed both types in Aviculopinna, an all-encompassing genus (Yancey 1978).

Excluding Pteronites

Still, pinnids with narrow elongate shells having regular, sharp growth lamellae lacked a proper generic name (Yancey 1978). So, Yancey created Meekopinna as a genus for these types. He then decided that the genus Pteronites was unavailable for americana-type pinnids since Pteronites was very different.

Yancey included an illustration on Plate 10 in the publication. He showcases both Meekopinna sagitta and Aviculopinna peracuta. The cross-section of Aviculopinna peracuta closely matches the specimens I find locally.

Original descriptions of Plate 10

10-11. Meekopinna sagitta (Chronic) Page 340

10. Internal view of right valve, with external growth lines showing through the valve; note the shallow groove just below the dorsal margin, which is formed by a curvature of the entire shell wall, X 1.5, UCMP 14381, Loray Fm., loc. UCMP D-5609.

11. Portion of an external mold of right valve, showing the form of the growth lines and growth lamellae on the dorsal two-thirds of the shell, X 2, UCMP 14382, Loray Fm., loc. UCMP D-5609.

12-13. Aviculopinna peracuta (Shumard) ? Page 341

External left valve view and posterior view of partial articulated specimen; the anteroventral part of the specimen is covered with matrix; note the thickened dorsal margin projecting above the main part of the shell, X 1, UCMP 14383, Pequop Fm., loc. UCMP D-5540.

14. Aviculopinna sp Page 342

External view of partial left valve, mostly covered with matrix; note the folding of the shell wall, X 2, UCMP 14384, Loray Fm., loc. UCMP D-5606.

Specimens of Interest Locally from the Brush Creek Limestone

Examples of a genus similar to Aviculopinna or Meekopinna are widespread in the local Brush Creek limestone. I do not find them in any stratum except for the calcareous limestone. They are absent from the shale thus far. Specimens often disarticulate as natural lateral breaks in the limestone traverse through the specimens. I’ve used Paraloid B-72 to reattach several specimens. I recovered all specimens below in local Brush Creek limestone within a one-half-mile radius. First, I review an example preserved flat, not in a life position.

A flat preserved specimen, CG-0112

Aviculopinna? sp. I recovered one excellent specimen (CG-0112) lying down, not in a life position. I found exquisitely preserved shell material and growth lamellae when I split the rock. I shared a photo with J. Harper, who has been studying the paleontology of gastropods and local geological formations over an entire career. He told me it was the best he had ever seen from the local section. From numerous photos of specimens I’ve reviewed online, it would appear this is the case.

I only partially prepared this specimen as I did not wish to risk destroying the preserved outside shell layer by removing more of the matrix. Instead, I planned on removing some extra material from the margins using a grinding wheel to lighten it and make it easier to store. Unfortunately, when I discovered this, I did not yet use a diamond cutting wheel on limestone, and the white line to the top and left of the specimen below was an attempt to cleave rock off with a large chisel.

Description of CG-0112

The specimen is elongate, subtriangular, with fine growth lamellae. It appears to be two valves, with the right more well-preserved than the left. This likely happened at the separation of the two halves of limestone. In my opinion, most paired shell valves should be preserved with the dorsal margin separating them. However, these two values are separated by the ventral margin. This is evident by the shape of the growth lamellae; the lines parallel to the ventral margin are near the vertical center.

The prismatic layer is well preserved over most of the rightmost valve in the photo. Attached preserved prismatic material is rare with locally recovered specimens, as this layer frequently remains attached to the matrix in recovered samples. The dorsal margin is hidden well, perhaps only on the posterior end. Further preparation may be necessary to expose parts of the anterior end.

Other specimens preserved in life position

Life position examples are the easiest to find and recover. They break free of the matrix easily, in some sort of recoverable detailed shape. The shell surface is challenging to recover, often adhering to the limestone matrix. The attachment between calcite shell layers vs. the calcite to limestone attachment is vastly different. Examples with the anterior termination preserved in whole can be rare, as they often extend below the limestone layer.

CG-0032, a wide specimen

Aviculopinna? sp. This specimen is subtriangular and elongate, with preserved growth lamellae along the ventral margin. The shell terminates at both the anterior and posterior margins. This specimen was repaired from two pieces and reattached perpendicular to the plane of symmetry. A bit of matrix extends through the ventral margin opening, where the shell was opened after death. There are a few areas of topmost shell growth lamellae preserved. Deeper growth lamellae patterns are visible, with deep, broad grooves on the shell surface.

The specimen is 6cm long along both the dorsal and ventral margins. It is 4 cm wide on the posterior end and 2.6cm wide on the anterior end.

A small anterior piece, CG-0115

Aviculopinna? sp. The specimen is the anterior section, with a nearly complete terminal beak. The lamellae are sharp and evenly spaced. The dorsal margin is 2.5 cm long, while the ventral is 3.2 cm. A small piece of limestone matrix adheres to the ventral side. I avoided the removal of the remaining matrix to preserve the growth lamellae. The lamellae running parallel to the ventral margin reach a sharp point at the anterior termination point. The termination was a mere 1 cm away, considering the angle between the dorsal and ventral margins. The prismatic layer is apparent but does not shimmer excessively with projected light.

Specimen CG-0116

The specimen is elongate, subtriangular, and narrow. It has been repaired using Paraloid B-72, with two pieces fused back together. The ventral margin is 6 cm long, while the dorsal margin is 5 cm. Preserved shell material near the ventral margin shimmers excessively with applied light. There is also a tiny portion of the shell material that reacts the same near the dorsal margin. Parts of the hinge at the dorsal margin remain on this specimen.

Specimen CG-0117

The specimen is elongate, subtriangular, and nearly round in cross-section. The ventral margin is 2.5 cm in length; the dorsal margin is 3 cm. The shell material present shimmers with projected light. The ventral margin is interesting as it rolls up to a sharp lip. The dorsal margin is missing the rolled hinge in preservation. The posterior end supports the near-circular observation; it measures 1.8 cm across the valves and 1.9 cm margin to margin. The anterior end is much different, being 1.1 cm across the valves and 0.8 cm margin to margin.

References

- Anelli, L.E. & Rocha-Campos, A.C., Simoes, M.G., 2016, Pennsylvanian Pteriomorphian bivalves from the Piaui Formation, Parnaiba Basin, Brazil., Journal of Paleontology – V80, Issue 6, pp. 1125-1141.

- Dauphin, Y. et al., 2018, The Prismatic Layer of Pinna: A Showcase of Methodological Problems and Preconceived Hypotheses, Minerals, 19 Pages.

- Geinitz, H. B., 1848, Die Versteinerungen des Deutschen Zechsteinge-birges. Dresden, p. 77, Plate XIV

- Meek, F.B., 1864, Remarks on the family Pteriidae, (=Aviculidae) with descriptions of some new fossil genera. The American Journal of Science and Arts, Second Series 37, pp. 212-220

- Munster, G.G., 1840, Beschreibung einiger seltenen Versteinerungen des Zechsteins. Beiträge zur Petrefacten-Kunde, p 45, Tab 3, Figure 4

- Shumard, B.F., Swallow, G.C., 1858, Descriptions of new fossils from the coal measures of Missouri and Kansas., St. Louis Academy of Science Transactions, p. 214

- Waller, T.R., 1978, Morphology, morphoclines, and a new classification of the Pteriomorphia (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (B), 248, pp. 345–365

- Yancey, T.E., 1978, Brachiopods and mollusks of the Lower Permian Arcturus Group, Nevada and Utah, Pt. 1, Brachiopods, scaphopods, rostroconchs and bivalves. American Paleontology Bulletins, 74(303), pp. 257–363

- Yancey, T.E., Amler, M., Raczyński, P., & Brandt, S., 2023, Rebuilding the foundation of late Paleozoic pinnid bivalve study (family Pinnidae). Journal of Paleontology, 97(1), pp. 140-151.

- 2021. Pinna nobilis, Wikipedia