The Paleozoic gastropod (snail) Shansiella carbonaria (Norwood & Pratten, 1855) is a common find at a Pine Creek limestone locality I collect from Armstrong County, Pennsylvania. I also recover specimens from the Brush Creek limestone. Examples of S. carbonaria are easy to come by (especially at the Pine Creek locality), and I find each to be unique and visually pleasing to examine. Norwood & Pratten described this medium-sized snail species more than 160 years ago as Pleurotomaria carbonaria. Percy Raymond, the Carnegie Museum’s first Assistant Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology, reported it locally from the Brush Creek and Ames Limestone (Raymond, 1909). Yin created the genus Shansiella in 1932. Years later, Knight, Batten, and others reassigned Pleurotomaria carbonaria to Yin’s new genus, Shansiella.

Roger Batten erected the Portlockiellidae in 1956 and placed Portlockiella kentuckyensis as the type species. He did so in a short article to allow publication of this family in the upcoming Treatise of Invertebrate Paleontology. Only two years later, Batten published a relatively large volume on Permian gastropods from the southern United States. He created two new species of Shansiella that have since been moved to the genus Permoconcha. Batten also performed detailed work in the 1970s using images generated by a scanning electron microscope. His work showcased the crystalized aragonite on S. carbonaria specimens from the Eastern United States.

In more modern times, Richard Hoare and others reported on the distribution of several Pennsylvanian fossil gastropods throughout the marine units in the Appalachian Basin. Specimens of Shansiella carbonaria are reported from ten of fourteen distinct Pennsylvanian-aged marine zones (Hoare et al., 1997). The species is often found in Upper Carboniferous publications such as Fossils of North Texas and Fossils of Ohio.

*Correction: The Glenshaw should be split in the figure above. The Ames, Gaysport, and Skelly are in the Casselman Formation.

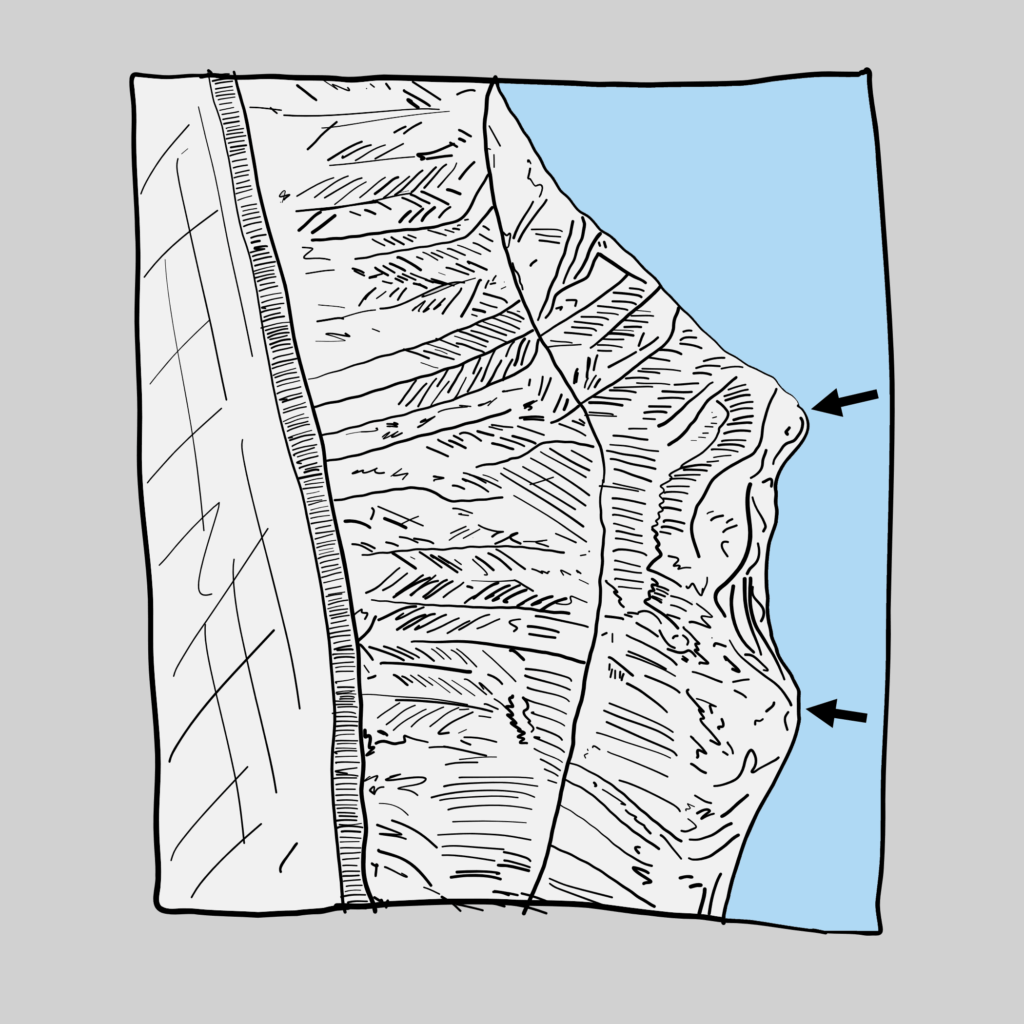

The Differences Between the Brush and Pine Creek Marine Zones

The Brush Creek limestone and the Pine Creek limestone are strata in the Glenshaw Formation. The Glenshaw and Casselman Formations make up the greater Conemaugh Group. The Ames Limestone divides the two formations and is the youngest reported horizon for S. carbonaria in the Appalachian Basin (Hoare et al., 1997).

The Pine Creek locality has yielded the majority of S. carbonaria specimens I have recovered. It also contains an abundance of gastropods within the available fossil fauna. Bivalves, cephalopods, and numerous horn corals make up the other significant faunas found in the fossiliferous rocks at the locality. I’ve also recovered smaller quantities of crinoid columns, brachiopods, and Petalodus teeth. The limestone and adjacent rock are very fissile. The gastropod specimens tend to have nearly all of the shells intact.

In comparison, the Brush Creek limestone is a non-fissile rock. Gastropods are less common at the Parks Township locale. The significant available fauna includes brachiopods, cephalopods, and bivalves. The bivalve genus Avliculpinna? is very abundant, which could help determine the paleoecology of the area. Recovered gastropods have their shells firmly adhered to rock, a common problem throughout the Appalachian Basin (Hoare et al., 1997).

In 1835, Conrad Described Turbo insectus

In 1832, Edward Miller, an assistant railway engineer, started work on a multi-year project to build the Allegheny Portage Railroad. The goal was to connect the two major canals in Pennsylvania by building inclined railway planes that pulled cars up and over the Allegheny Mountains. The canals ran along the Juniata and Conemaugh rivers and were used to transport materials and people. The Conemaugh Group, which contains the Glenshaw Formation, is named after outcrops along the Conemaugh River.

During construction, Miller would spend his idle time examining exposed rock outcrops. He later authored a geological report presented to the Geological Society of Pennsylvania. In the report, he wrote that “great numbers of shells were loosed and fell out” during the removal of large rocks during excavation (Miller 1835).

Timothy Abbott Conrad described five marine fossils from specimens Miller had sent to the society. Turbo insectus was one of the five. However, Conrad’s mention of this species would be the last. The species has not been reported on again since Conrad’s original writing.

While impossible to confirm in modern times, Percy in 1909, Girty in 1937, Sturgeon in 1946, and Harper in 2016 considered Conrad’s specimen of Turbo insectus to likely be the modern Shansiella carbonaria. The shell features a similar profile and corded ornamentation. It came from a locality that correlates with the Brush Creek marine zone. The biggest thing that casts doubt from a visual inspection is the general shape. Being a simple illustration, it’s possible that this may not represent an exact morphological depiction of the original specimen.

Conrad’s Description

The original description was short and hard to read by today’s standards. Conrad uses “whirls” instead of “whorls.” The description is a single sentence.

TUBRO, Lam.

T. insectus. Pl. 12, fig 4. Shell turbinate, ventricose, with prominent coarse revolving striae; whirls convex, flattened above; aperture orbicular, about half the length of the shell.

The specimen reported on has not been found in any paleontological collection. This makes Turbo insectus impossible to validly synonymize with Shansiella carbonaria. Therefore, Norwood & Pratten are the original authors of the species. Sturgeon mentioned a possible way to synonymize the two. Still, it would require recovery of S. carbonaria from the type locality and proof that T. insectus is unavailable, as Conrad had only illustrated the specimen and failed to preserve the holotype.

The fossil description itself is, in fact, an important historical event. It was part of the first confirmed descriptions of Pennsylvanian marine invertebrates from North America (Harper, 2016). Conrad’s 1835 paper was the first published North American report of Pennsylvanian marine fossils.

Norwood & Pratten Describe Pleurotomaria carbonaria.

The original description from 1855 discusses a specimen that is a small to medium-sized shell, 1 inch in length. It was said to have sharp, longitudinal ribs. This is different than the description in the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, which calls these rounded cords. Perhaps variation in the recovery matrix could make particular specimens have sharp ribs, or maybe there is variation across different species. Nevertheless, I believe that Norwood & Pratten’s “sharp” was a macro observation, whereas the Treatise is more of a micro observation.

Shell of medium size. Length, 1 inch; breadth, 1 l-20th inch. Whorls five, rounded, covered with strongly raised, sharp, longitudinal ribs, the grooves or furrows between which are rounded, and much broader than the ribs themselves. The sinus consists merely of a broader groove, in which there are two or three raised ribs similar to those on the remainder of the shell, but much smaller. On the inferior half of each whorl, below the sinus, both the ribs and furrows are much smaller than those on the upper portion Mouth nearly semicircular; lip sharp.

Geological Position and Locality. — This species appears to be very rare, having been found only at Rock Creek, Williamson County, Illinois, where it occurs in a black, carbonaceous shale, belonging to the coal measures.

Explanation of the Figure. — PL IX. fig. 8. View of the front and left side of an adult specimen.

Illinois State Collection.

The description calls the species rare, only found from a shale belonging to the coal measures at Rock Creek, Williamson County, Illinois. This is clearly not the case today, as several examples are found all over the Earth. In just a short research time, I have seen reported specimens from Kentucky, Ohio, Texas, Pennsylvania, and New Mexico.

A Local Report of Pleurotomaria Carbonaria (=Shansiella Carbonaria)

In the 1910 Annals of the Carnegie Museum, Percy Raymond reported specimens from two marine horizons locally. A single example was illustrated from the Brush Creek, recovered from Donohoe, PA. Unfortunately, no specimen number exists, so it is currently unknown if this is in Carnegie’s Invertebrate Paleontology Collections, today managed by Albert Kollar. One interesting detail was Percy’s recalling of Conrad’s first described fossils back in 1835. It was in the 1910 publication that he discussed Turbo insectus and its similarity to Pleurotomaria carbonaria.

Helen Morningstar Illustrates a Specimen from the Pottsville of Ohio.

In 1922, Helen Morningstar published a large volume on Ohio’s Stratigraphy and Fossils of the Pottsville Formation. In the section about fossils, she discusses the condition of recovered specimens and talks about several shells in an “excellent state of preservation.” She mentions that several different species within Pleurotomaria might be referable to P. carbonaria. Morningstar discusses the profoundly depressed slit band. Her publication includes several localities throughout Eastern Ohio and lists available species, including P. carbonaria. She discusses five species of Pleurotomaria, along with some internal molds.

T. H. Yin Creates the Genus Shansiella in 1932.

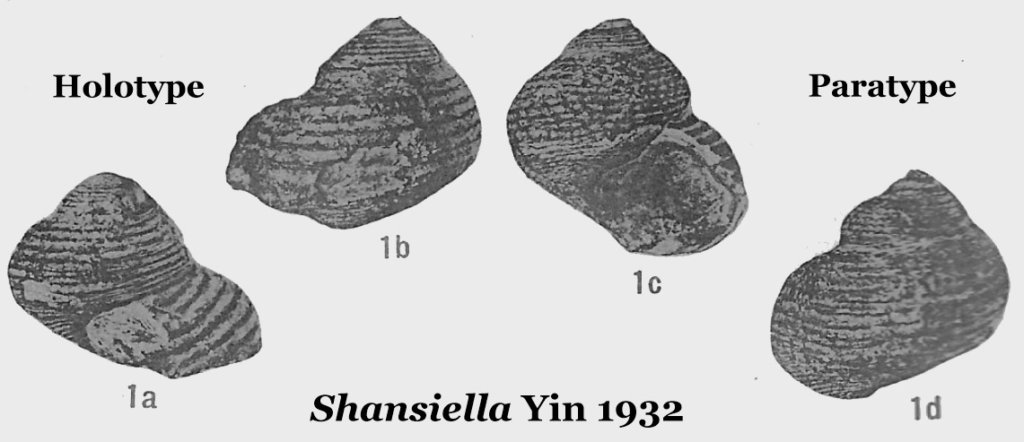

As part of a report on the Gastropoda of the Penchi and Taiyuan Series of Northern China, T. H. Yin erected the new genus Shansiella. He includes two catalog numbers, No. 4788 and No. 4789, for the holotype and paratypes of the genus. Workers collected them from the T’umen shale in the upper Taiyuan series, an Upper Carboniferous aged series.

Paleontology is not always a safe job despite being grounded in peaceful intentions. Yin mentions a colleague, Y. T. Chao, would have done work on both Gastropods and Cephalopods from the region. However, he notes that bandits took Chao in 1929. Yin was completing at least part of the work, publishing on the Gastropods of the area.

Yin’s Original Description of His New Genus Shansiella.

Genus SHANSIELLA Yin (gen. nov.)

Shell of medium size, rather low spired, the maximum diameter of the last whorl being a little greater than the total height of the shell. The general outline of the whorls is rounded but a narrow spiral depression is occupied by the slit-band. The suture is deeply impressed below the ambitus and on the edge of the slit-band.

The surface of the entire shell is covered by numerous spiral lines more or less granulated. The slit-band lies immediately below the ambitus and is not very strongly excavated.

The aperture so far as it is observable is subrhomboidal with rounded corners. The external lip expands strongly outward before arriving at the margin, which is suddenly contracted. This gives rise to an ungraceful protuberance near the aperture where the suture terminates far below the slit-band of the preceding whorl. No umbilicus is present.

The genotype is Shansiella altispiralis (Grabau). The author is not acquainted with any form previously described that can be referred to this genus.

Yin figured two specimens in four views. His “ungraceful protuberance” was visible in 1a in figure 5 below. Comparing 1b and 1c, one can see how different the shape was. It’s also important to note that Yin made no comparison to Pleurotomaria carbonaria. However, he did set his new genus under the family Pleurotomariidae. He mentions that Shansiella altispiralis was synonymous with Gyronema? altispiralis Grabau from the Permian of Mongolia.

I sent an inquiry to researchers who could check the institution that was supposed to hold the holotype and paratype and discovered that both specimens were missing. Specimens 4785 through 4792 are missing and likely lost forever. Yin’s illustrations are now the only reference for the holotype.

Eirlys Grey Thomas Erects the Genus Latischisma.

In the 1930s, Yin’s creation of Shansiella created some collisions and healthy discussions around the placement of his new snail genus. For example, in 1940, Eirlys Grey Thomas, a Carnegie Research Scholar from the University of Glasgow, reviewed the Pleurotomariidae in the Carboniferous limestones of Scotland. In the publication, she created a new genus Latischisma. She indicated its key features: the globose shell, the flattened selenizone, and its spiral ornamentation.

The published illustrations and specimen photos are identical to specimens of Shansiella. In 1958, Roger Batten remarked about the differences, whereas Shansiella has coarser ornament and Latischisma has finer. He assessed that this had been found to intergrade within a single species (Batten, 1958) and therefore synonymized the two. Batten’s remarks again touch on the corded versus sharp ornamentation difference. A few years later, when the Treatise volume was published, Latischisma was listed as a synonym of Shansiella.

Knight’s Discussion on Yin’s Specimens.

Nine years later, Knight (1941) reviewed Yin’s description of Shansiella and doubted Yin’s assessment of his specimens. While Yin provided photographs, the photos were all that were available to study. Specimens No. 4788 (holotype) and No. 4789 (four paratypes) are likely in a collection in Northern China. Yin said that the aperture had an “ungraceful protuberance” on the aperture. Essentially, the nearly circular aperture was squashed down to an oval. Knight concluded that Yin was “deceived by a broken aperture distorted by pressure” (Knight, 1941). He also considered the paratype that Yin illustrated as a much better specimen.

Sturgeon’s Research from the Allegheny Formation in Ohio

Myron T. Sturgeon included explicit remarks about S. carbonaria in his paper. Along with the stratigraphic correlation of specimens across the Allegheny Formation, he discusses Yin’s samples and Turbo insectus. He said Yin’s figures are not markedly different from his representatives (Sturgeon, 1946). This creates speculation about whether Shansiella altispiralis and S. carbonaria might be the same species.

Sturgeon was also one to openly question the validity of Turbo insectus and its relationship with S. carbonaria. He believed that the recovery of topotype material could prove the two specimens the same. Sturgeon also mentioned that since T. insectus had priority, the entire species would need to become Shansiella insectus (Conrad, 1835)

He mentions that S. carbonaria has a wide stratigraphic and geologic range and suggests a detailed study of various specimens across these ranges could turn up additional species or subspecies. While in modern times, efforts such as my own have helped publish visual samples to study online, the vast majority of collections in highly respected institutions do not include photographs. Photos can request them, but there is no standard path to follow, and results vary by institution.

Roger Batten Creates the Family Portlockiellidae

To publish new families for the upcoming Treatise of Invertebrate Paleontology, Roger Batten published the description for a new family of gastropods named Portlockiellidae. His publication included Portlockiella Knight (1945) and the new genus Tapinotmaria. Just a few years later, the Treatise was published, and the new family. S. carbonaria (Norwood & Pratten, 1855) was illustrated as a typical species of Shansiella. Knight et al. assigned Shansiella to the new family in 1960. The genus Portlockiella Knight, 1945, contrasts with Shansiella by having a deeper selenizone below the upper whorl sutures. The spiral ornamentation also has broader interspaces (Amler & Heidelberger, 2003).

Roger Batten Gets Closer Than Anyone

Microscopic studies of paleontological remains can be an excellent way to gain insight into how the original creature lived. It can help with species identification in fossilized trees that require views of the cellular structure (Gar Rothwell, 2021, personal comm.). Microscopic pictures can show specific crystal structures of one or more layers in the shells of mollusks.

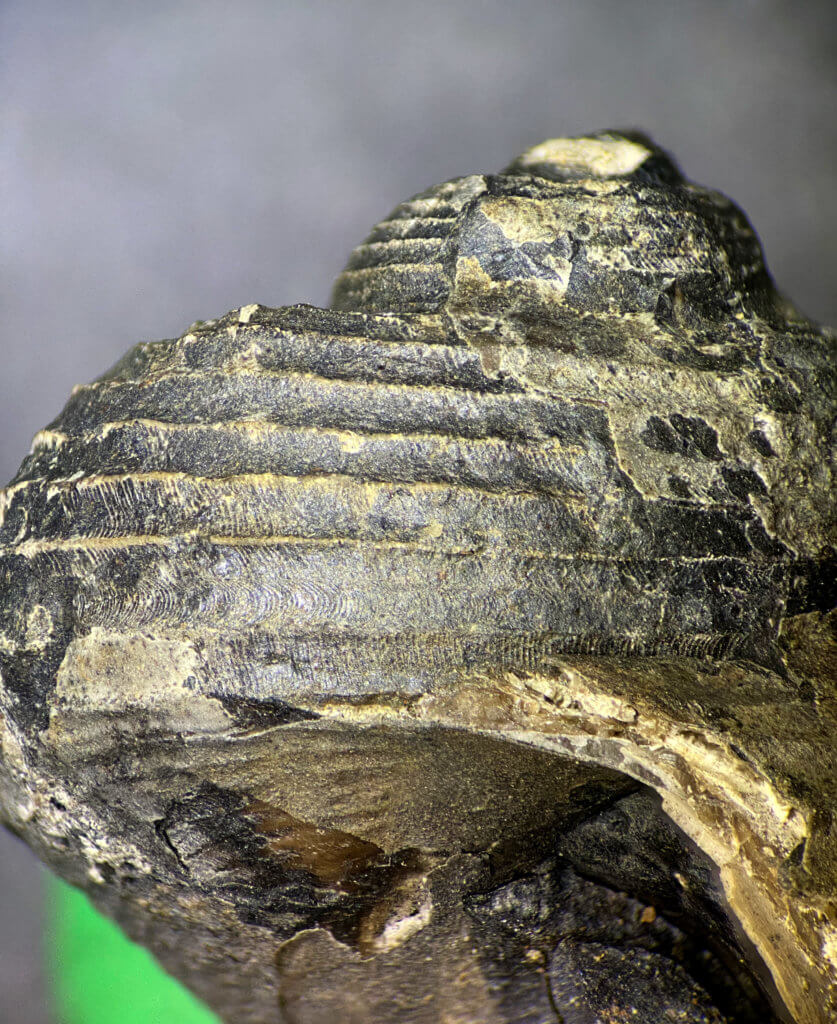

Batten provided scanning electron microscope images of Pennsylvanian pleurotomarian gastropods in a paper published in an American Museum Novitates in 1972. S. carbonaria was featured in the vast majority of images in the paper. A nice cross-section of an ornamental rib is presented in figure 14 in the paper. This adds more to the sharp versus rounded rib discussion. This particular rib includes two subsidiary peaks with a slight depression between them.

Another fascinating insight came from Figure 16 in the paper showing a total cross-section of S. carbonaria. Gastropods are typically interesting in this view, showing matrix-filled shell voids. Batten discusses the nacreous inner walls and irregular shell thickness at different places. I considered cutting one of my specimens to get this view (I did cut one later), but the photo from the article presents a great view. I illustrated Batten’s figure below.

Reviewing The Morphometric Differences in Local Shansiella carbonaria Specimens.

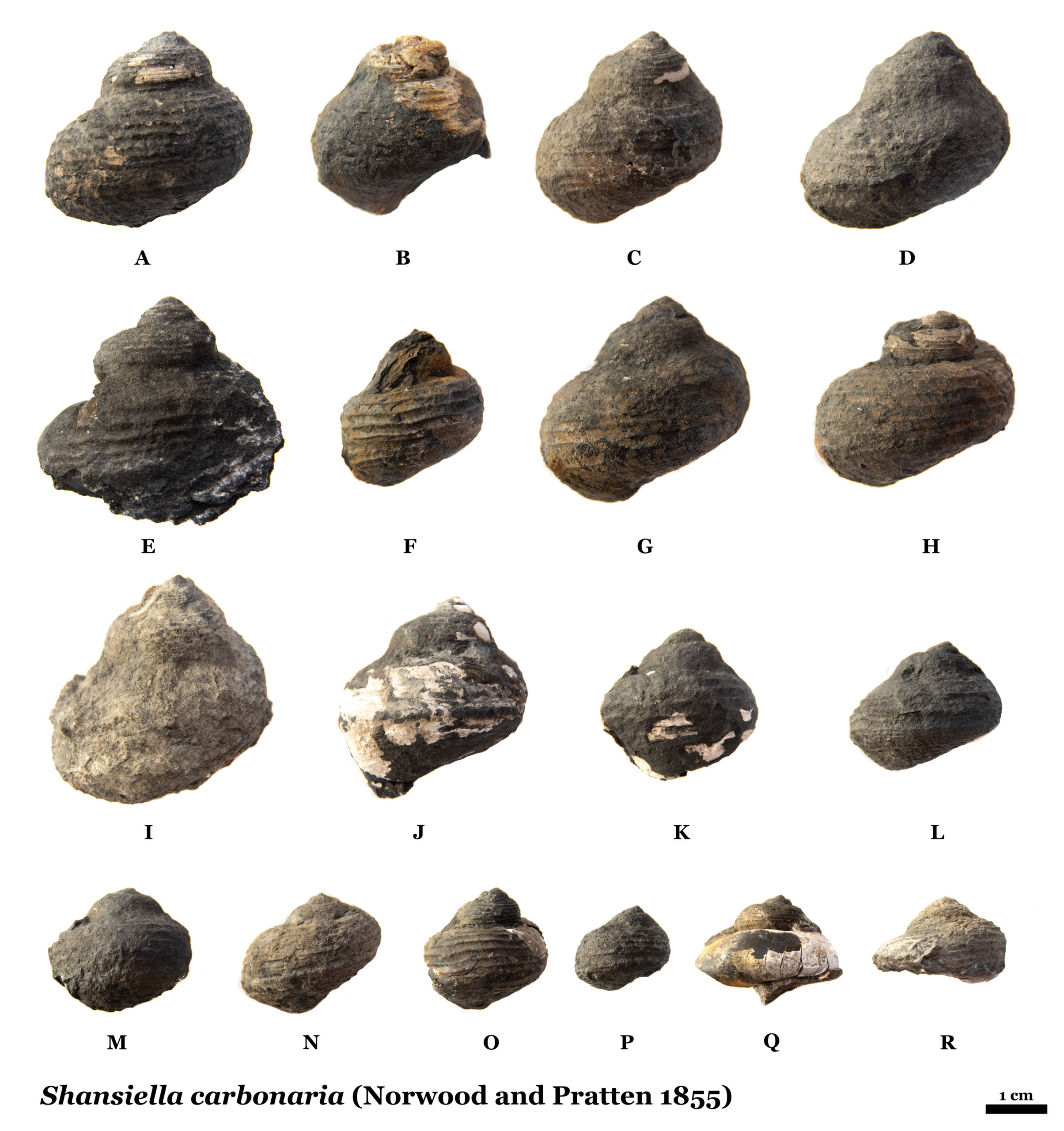

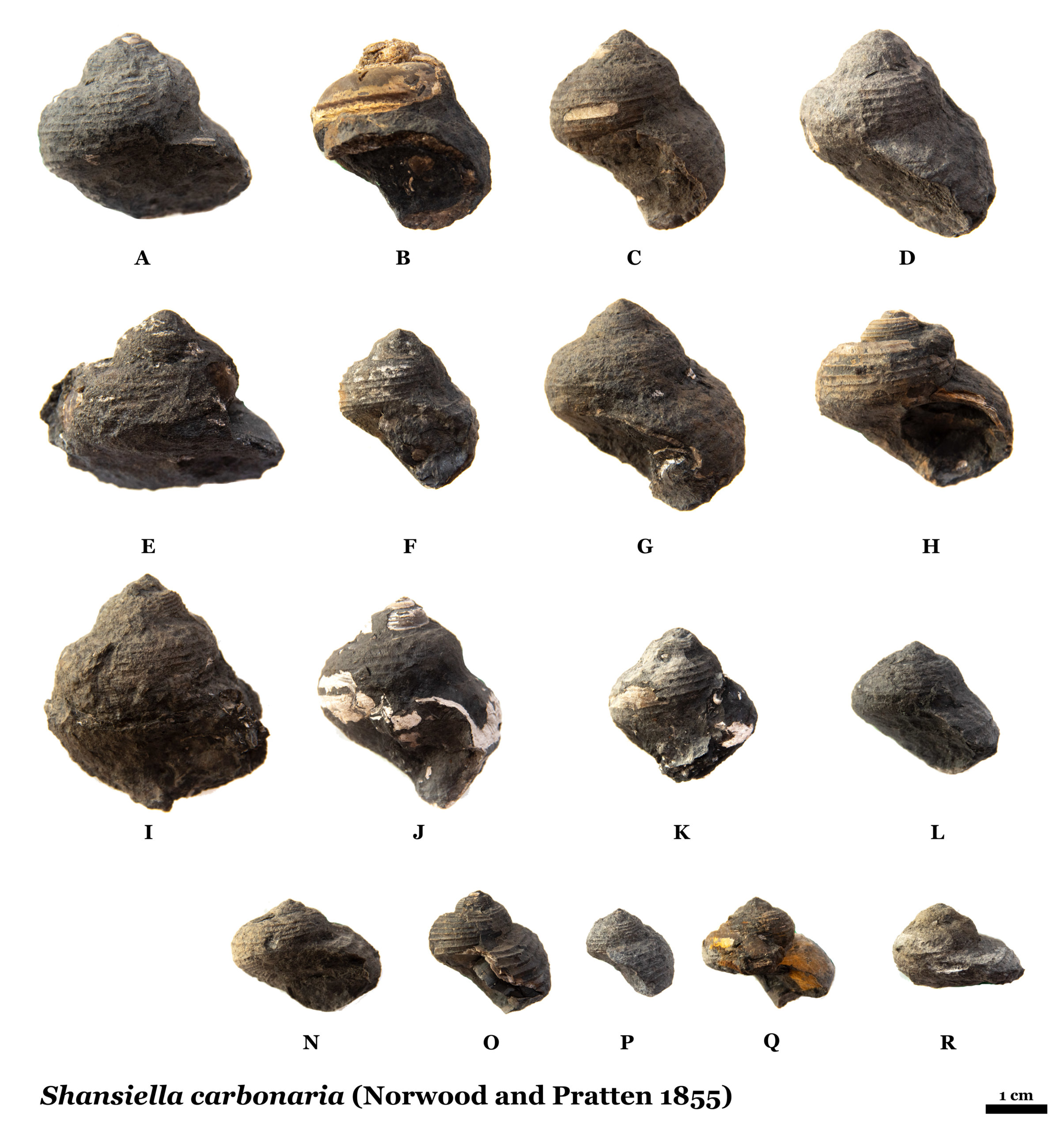

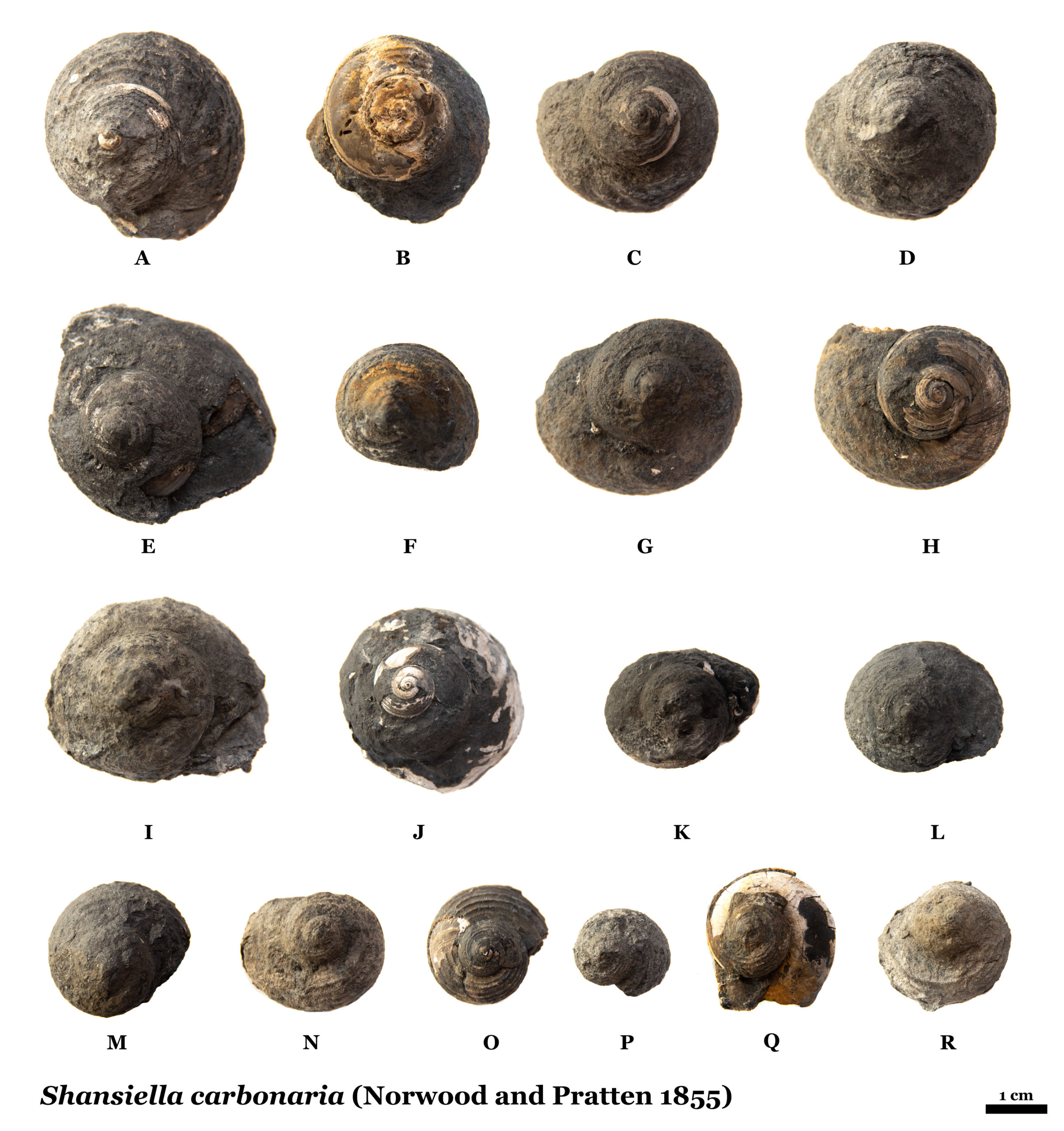

The recovery of over twenty-five different specimens has yielded a variety of shell sizes. Specimens recovered from the Pine Creek locality have produced detailed shell views. Shansiella found locally in the Brush Creek limestone are more challenging to recover and observe. As part of this research, I have prepared plates. The first plate is a broad overview of specimen size—plates 2, 3, and 4 show three views of eighteen specimens. Plate 5 shows a rather extreme compression comparison.

All specimens are not well cleaned. Over time I have developed new techniques for cleaning. The samples below could be cleaned to show more detail.

Plate 1 – Views of Eleven Specimens of S. carbonaria

This plate showcases a broad range of shell sizes found in the Pine Creek and Brush Creek horizons in central and southwestern Armstrong County, Pennslyvania.

Plate 1. Shansiella carbonaria (Norwood & Pratten, 1855), from the Brush Creek and Pine Creek limestones of Armstrong County, Pennsylvania, United States. All reside in the author’s collection. Correlation with figure labels and specimen identification numbers is as follows: (A) CG-0218; (B) CG-0195; (C) CG-0203; (D) CG-0197; (E) CG-0202; (F) CG-0149; (G) CG-0217; (H) CG-0060; (I) CG-0189; (J) CG-0225; (K) CG-0219;

Plate 2 – Abapertural View of Eighteen Specimens of S. carbonaria

The plate below provides a good range of shell sizes and preservation throughout the Brush Creek and Pine Creek marine zones in Western Pennsylvania. The corded ornament is not always well preserved, but all eighteen specimens show at least the presence of these cords on one or more whorls. Each example averages 3-4 whorls with some variation. The smallest whorl at the spire is often well preserved, as the pyramid shape helps to prevent damage to the spire.

Plate 3 – Adaperture View of Seventeen Specimens of S. carbonaria

The aperture is not often well preserved. Several authors focus on aperture morphology. The shell is thick-walled in this area. Specimen B and H both show a very thick shell wall. Specimen O is exceptional as it shows distinct layers within the fossil shell material.

I omitted M because I did not take a photograph in this view for the specimen.

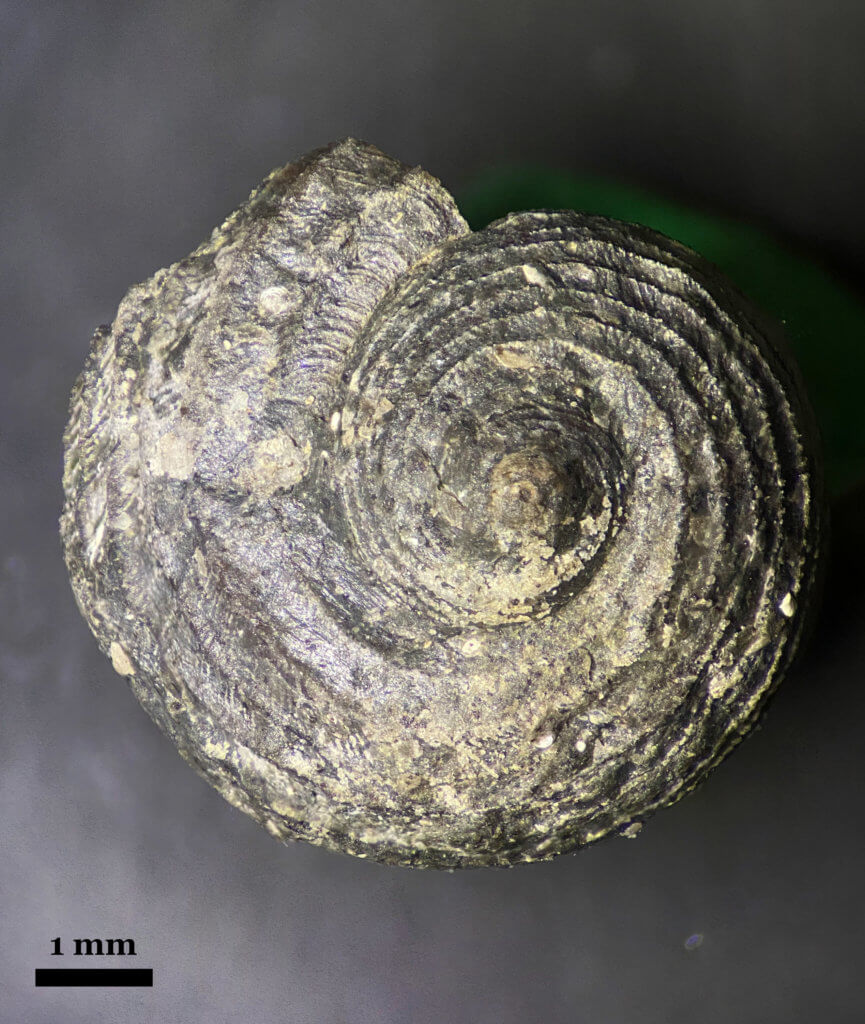

Plate 4 – Spire View of Eighteen Specimens of S. carbonaria

The view from above the specimens is pleasing. In cleaner examples, you can see the growth lines. You can see these growth lines in specimens H and O. The cords maintain visibility on each whorl when viewed directly above.

Plate Key for Plates 2 – 4

Plates 2-4. Shansiella carbonaria Norwood & Pratten, 1855, from the Brush Creek and Pine Creek limestone of Armstrong County, Pennsylvania, United States. All reside in the author’s collection. Correlation with figure labels and specimen identification numbers is as follows: (A) CG-0218; (B) CG-0185; (C) CG-0195; (D) CG-0216; (E) CG-00142; (F) CG-0203; (G) CG-0197; (H) CG-0202; (I) CG-0166; (J) CG-0145; (K) CG-0148; (L) CG-0149; (M) CG-0215; (N) CG-0217; (O) CG-0060; (P) CG-0189; (Q) CG-0147; (R) CG-0151;

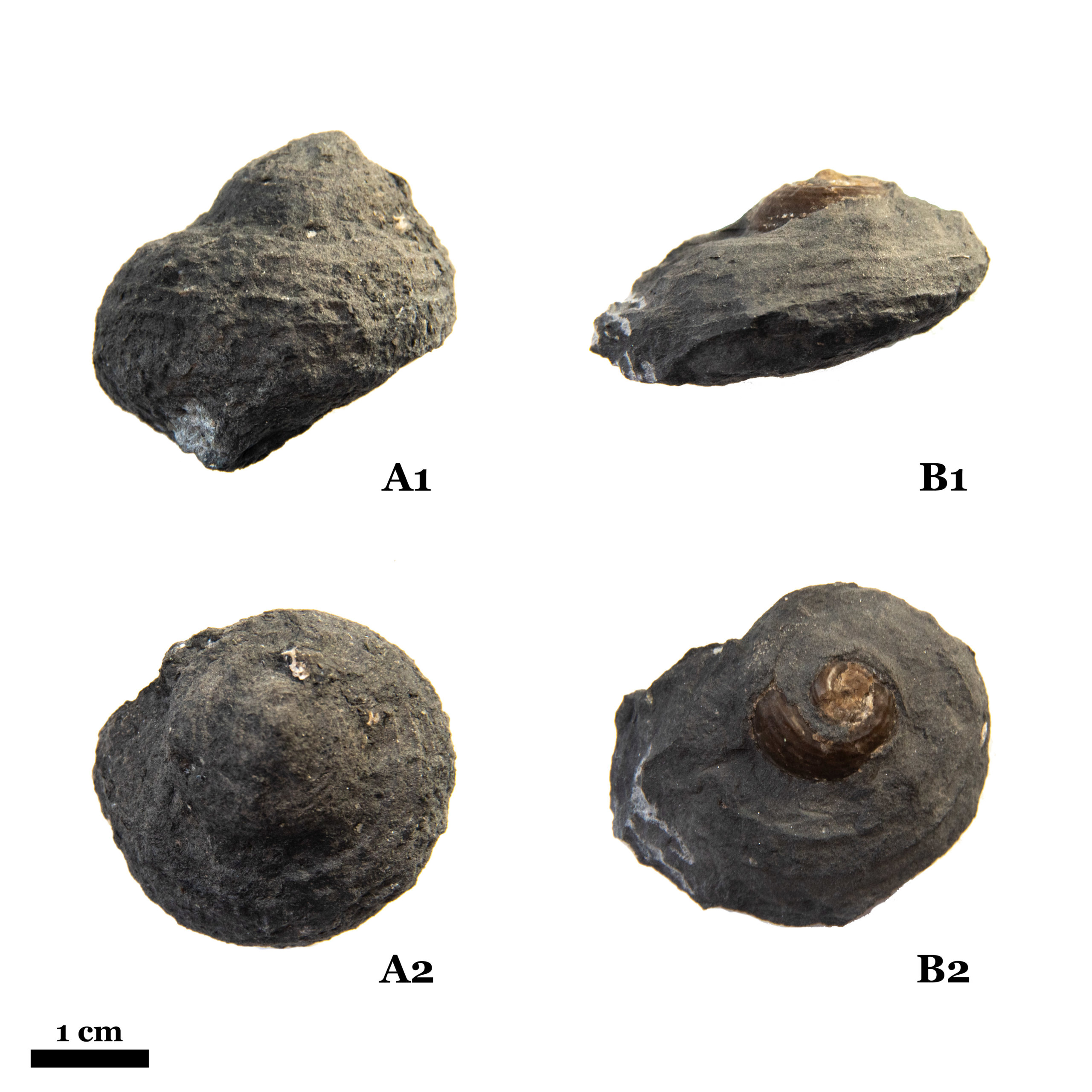

Plate 5 – Shell Compression After Burial

The following plate showcases four views of two specimens, CG-0221 and CG-0222. The former specimen is a typical recovered specimen with a whole spire. The latter is highly compressed vertically.

Plate 5. Shansiella carbonaria Norwood & Pratten, 1855, from the Pine Creek limestone Armstrong County, Pennsylvania, United States. All reside in the author’s personal collection. Correlation with figure labels and specimen identification numbers is as follows: (A1, A2) CG-0221; (B1, B2) CG-0222;. Note the difference in vertical preservation between A1 and B1. While it appears that perhaps the bottom of the shell is missing, inspection shows a full set of spiraling ornamentation on the underside.

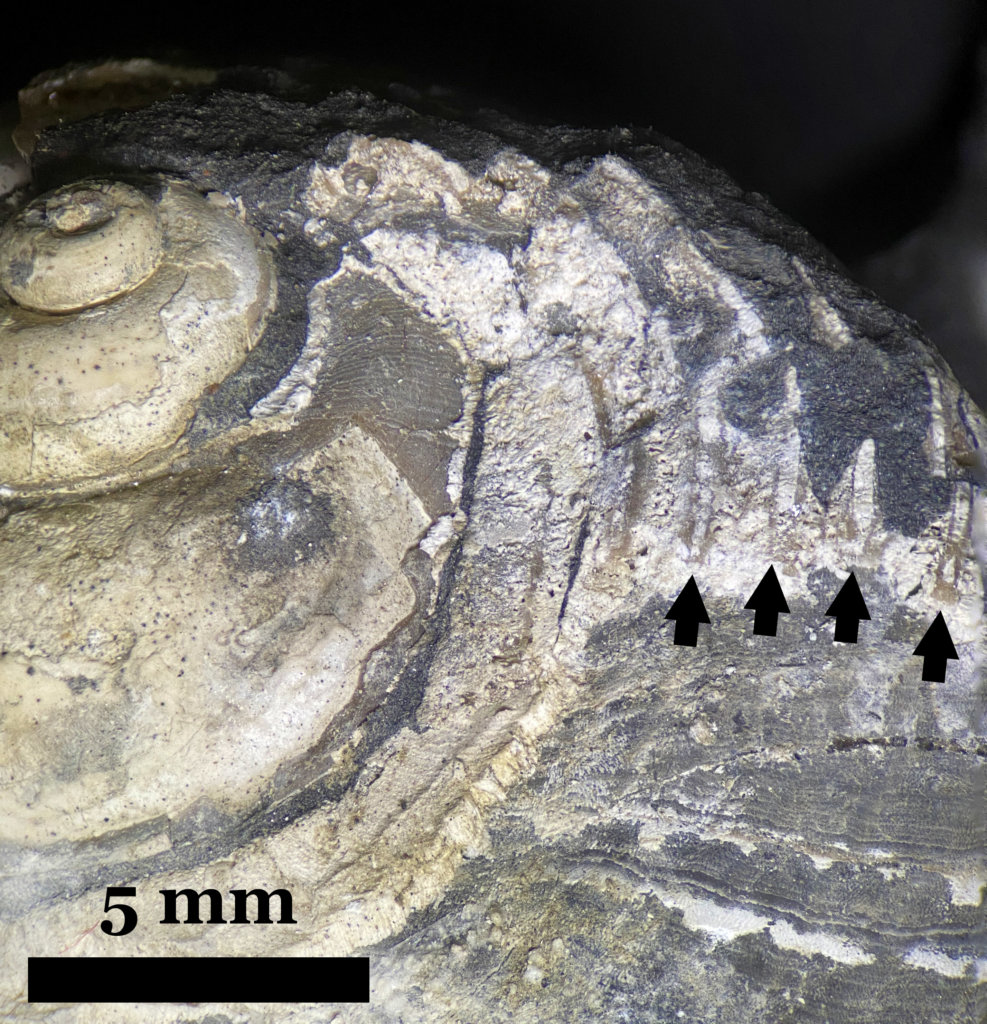

Specimen CG-0060 and Some Excellent Feature Preservation.

The specimen CG-0060 is a smaller specimen with several well-preserved features. The outer shell material is missing at two places on the shell. However, growth lines from inside the shell are visible. Outer shell growth lines are also visible on this specimen. When viewed up close, clean separation from the matrix created an exceptional representative.

Figure 10b—CG-0060, Shansiella carbonaria. Enhanced detail using ammonium chloride. Scale bar = 5 mm.

Juvenile Specimen CG-0219, a Tiny but Detailed Example

The scale bar on photos of CG-0219 Shansiella carbonaria is in millimeters, not centimeters. Despite its tiny size, there is a lot of detail available with this particular fossilized gastropod. The aperture is a bit more intact than typical recovered examples. In particular, the preserved growth lines are exceptional. They are difficult to see along the selenizone, but small parts can be observed. The broader channel between the costae where the selenizone runs is easy to discern.

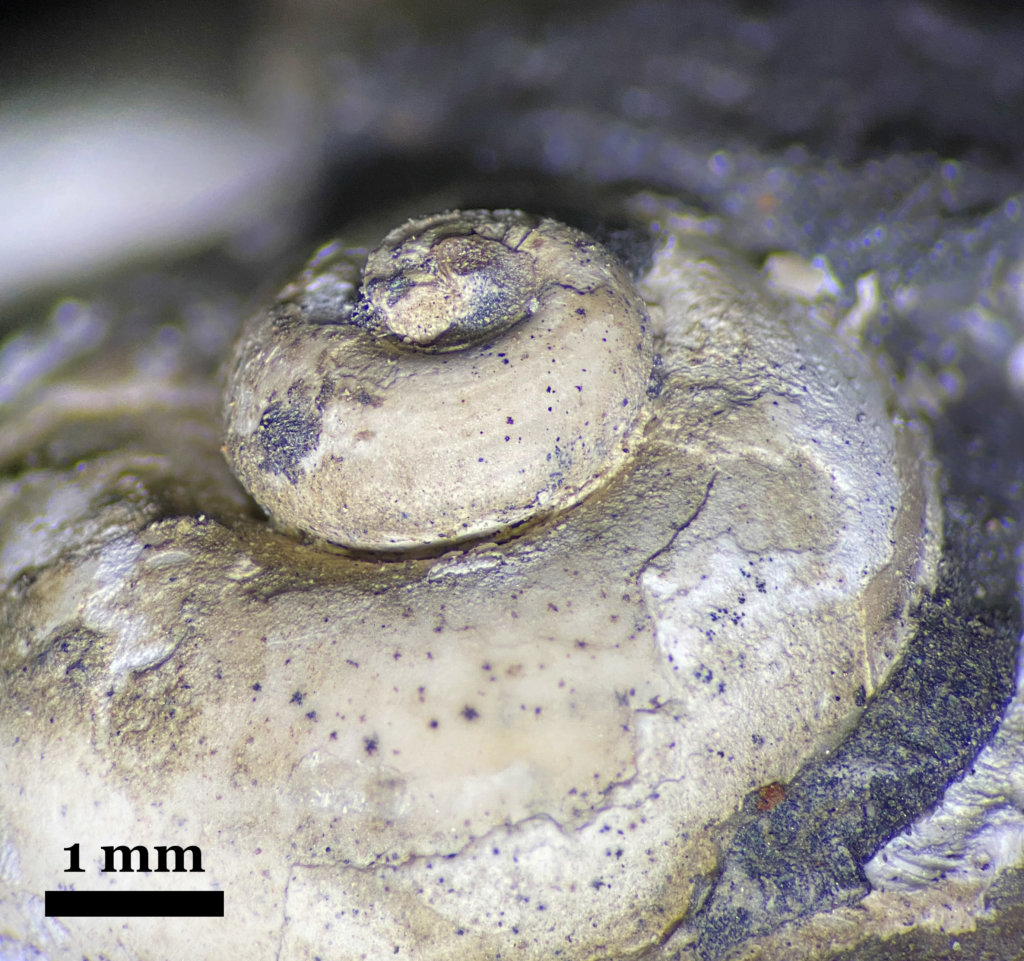

Specimen CG-0226, Weathered Example

This heavily weathered specimen provides some detailed depth into the shell matrix. Most striking is the characteristic of eroded ornament structures showing differing weathering on the topmost ridges versus the central concave depression. Figure 12 shows these structures. The more solid peaks are visible with a powdery white central depression that has eroded differently.

Another interesting feature of CG-0226 is how preserved the spire is. While most of the outer shell material has eroded in this view, the inner shell layer is maintained. The spire wraps around the columella. The ornament lines can be seen barely on the whorl. This photo shows how rapidly the whorls can expand with each revolution.

CG-0424, A classic example of Shansiella carbonaria

Shansiella carbonaria Catalog Entries

- All catalog specimens collected locally are available at this link.

Specimens at Different Institutions

Yale Peabody Museum

The Yale Peabody Museum has five catalog entries for S. carbonaria, all recovered from Kentucky. Some are lots, and the total number of specimens is thirteen. Two are listed under the older name Pleurotomaria carbonaria, but correct identification exists within each record. At least one of them was collected over 100 years ago, in 1919. They currently do not have photographs attached to these records. I was not able to review any of the specimens visually, but I include them for further reference of the collected material.

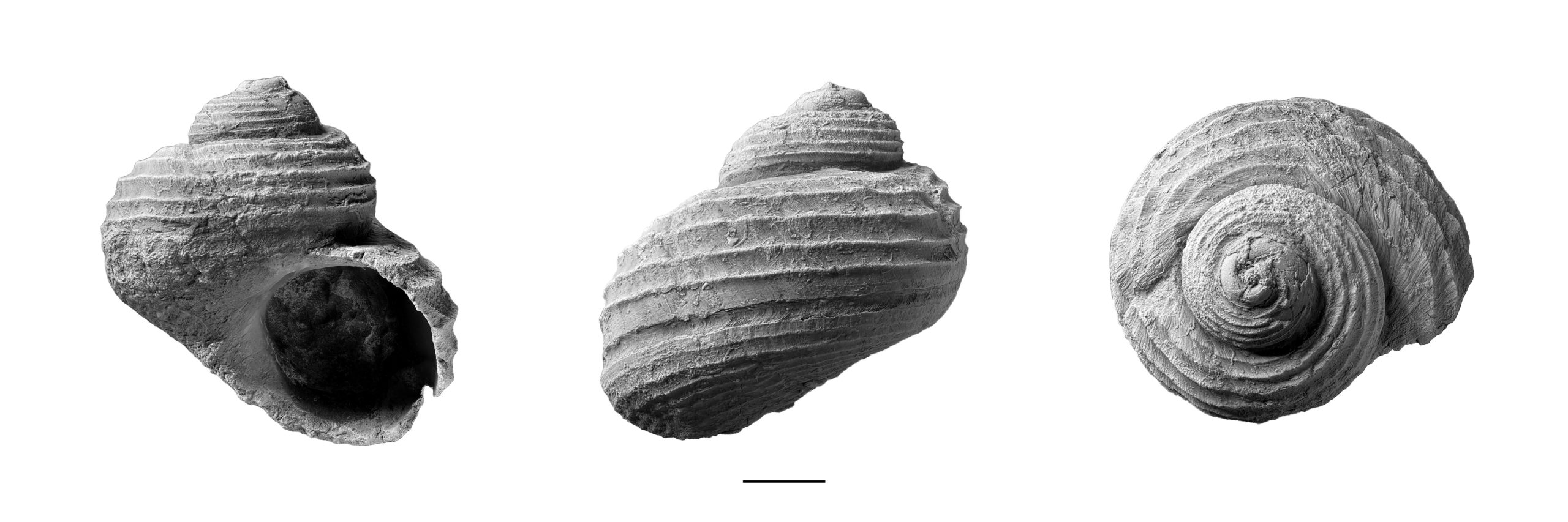

University of New Mexico

In a conference paper in 1984, Barry S. Kues listed and figured a single specimen of S. carbonaria from the Flechado Formation in North Central New Mexico. Many of the listed genera are similar to ones back in Parks Township, including Metacoceras, Mooreoceras, Petalodus, Linoproductus, Worthenia, and Wilkingia. The list in his research is very comprehensive and spans eight papers over 50+ years. In another report in 2001, Kues and Batten illustrated both UNM 7057 and 7058. UNM 7057 was said to be three times larger than UNM 7058.

- UNM 7057

- UNM 7058

American Museum of Natural History

Batten referenced several specimens of S. carbonaria over a long career of paleontology writing. He deposited eleven of them into the collection of the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History. They have a well-functioning online catalog, and to my surprise, all of Batten’s specimens were there. Three of them even include photos.

- AMNH 29222 [Photo]

- AMNH 29223

- AMNH 29225

- AMNH 29227

- AMNH 29228

- AMNH 29229

- AMNH 29231 [Photo]

- AMNH 29232 [Photo]

- AMNH 29233

- AMNH 29234

- AMNH 29235

Smithsonian Museum of Natural History

There are two entries in the Smithsonian Catalog. One of them was collected from Kentucky; the other is unknown.

Acknowledgments

I want to express my most profound appreciation to John A. Harper for his peer review of this paper, for his help in educating me in invertebrate paleontology, and for pointing out the Pine Creek locality in which the majority of these specimens are from.

References

- Amler, M.R.W., Heidelberger, D., 2003, Late Famennian gastropoda from south-west England, Palaeontology, 46(6), pp. 1151-1211

- Batten, R.L., 1956, Some new pleurotomarian gastropods from the Permian of west Texas, Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 46(2): 42

- Batten, R.L., 1958, Permain Gastropoda of the Southwestern United States. 2, Pleurotomariacea: Portlockiellidae, Phymatopleuridae, and Eotomariidae, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, v. 114, Article 2, pp. 157-246

- Batten, R.L., 1972, The Ultrastructure of Five Common Pennsylvanian Pleurotomarian Gastropod Species of Eastern United States, American Museum Novitates, No, 2501, Aug 21, 1972, pp. 1-34

- Conrad, T.A., 1835, Description of five new species of fossil shells in the collection presented by Mr. Edward Miller to the Geological Society: Geological Society of Pennsylvania Transactions, v. 1, pp. 267–270

- Feldmann, R.M., 1996, Bulletin 70: Fossils of Ohio, State of Ohio Div. of Geological Survey, p. 15 & pp. 162-163

- Fossilworks, 2021, Taxonomy page. http://fossilworks.org/?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=79442

- Girty, G.H., 1915, Fauna of the Wewoka formation of Oklahoma, United States Geological Survey Bulletin 544, 353 pp.

- Girty, G.H., 1937, Three Upper Carboniferous Gastropods from New Mexico and Texas, Journal of Paleontology, Vol 11, No 3, pp 202-211.

- Harper, J.A., 2016, North America’s First Pennsylvanian Marine Invertebrate Fossil Locality, Geology, v. 46, no. 4, pp. 3–14

- Hoare, R.D., 1961, Desmoinesian Brachiopoda and Mollusca from southwest Missouri, University of Missouri Studies Volume XXXVI pp. 159-160, p. 263

- Hoare, R.D., Sturgeon, M.T., and Anderson Jr., J.R., 1997, Pennsylvanian Marine Gastropods from the Appalachian Basin, Journal of Paleontology, Vol. 71, No. 6 (Nov. 1997), pp. 1019-1039

- Knight, J.B., 1941, Paleozoic gastropod genotypes. Geological Society of America Special Paper 32, 510 pp.

- Knight, J.B., 1944, Paleozoic Gastropoda, Index Fossils of North America, pp. 437-479

- Knight, J.B., Cox, L.R, Keen, A.M., Batten, R.L., Yochelson, E.L., and Robertson, R., 1960, Systematic Descriptions (of Mollusca – Gastropoda), Treatise On Invertebrate Paleontology Part I Mollusca, p I211-I212

- Kues, B.S., 1984, Pennsylvanian stratigraphy and paleontology of the Taos area, north-central New Mexico, New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 35th Field Conference, pp. 107-114

- Kues, B.S., Batten, R.L., 2001, Middle Pennsylvanian gastropods from the Flechado Formation, north-central New Mexico. Journal of Paleontology 75, (Supplement), 95 pp.

- McKenzie, M., and McLeod, J., 2003, Pennsylvanian Fossils of North Texas, Occasional Papers Volume 6 by the Dallas Paleontological Society, 2003

- Miller, E., 1835, Geological description of a portion of the Alleghany Mountains, illustrated by drawings and specimens: Transactions of the Geological Society of Pennsylvania, v. 1, pp. 251–255.

- Morningstar, H., 1922, Pottsville fauna of Ohio. Ohio Geological Survey, Bulletin 25, 312 pp.

- Norwood, J.G., and Pratten, H., 1855, Notice of fossils from the Carboniferous Series of the western states belonging to the genera Spirifer, Bellerophon, Pleurotomaria, Macrocheilus, Natica, and Loxonema, with descriptions of eight new characteristic species. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 3: pp. 71-77

- Raymond, P.E., 1910, A preliminary list of the Fauna of the Allegheny and Conemaugh Series in Western Pennsylvania, Annals of the Carnegie Museum, pp. 144-158

- Sepkoski, J. J., 2002, A Compendium of Fossil Marine Animal Genera. United States: Paleontological Research Institution, 560 pp.

- Sturgeon, M.T., 1964, Allegheny Fossil Invertebrates from Eastern Ohio: Gastropoda. Journal of Paleontology, 38(2), pp. 189-226

- Thomas, E.G., 1940, IV.—Revision of the Scottish Carboniferous Pleurotomariidae, Transactions of the Geological Society of Glasgow, Vol 20, pp 30-72

- Yin, T.H., 1932, Gastropoda of the Penchi and Taiyuan Series of North China, Palaeontologica Sinica, Series B.

- Yochelson, E.L., and Saunders, B.W., 1967, A bibliographic index of North American late Paleozoic Hyolitha, Amphineura, Scaphopda and Gastropoda. United States Geological Survey Bulletin Series 1210, pp. 1-271