I started my research thinking this fossil was Mahoningoceras Murphy 1974, then later thought it was smashed, had straight flank sutures, and was a Millkoninckioceras Kummel 1963. I reversed this decision again after comparing it to Millkoninckioceras and refocused on Mahoningoceras. Yet, I received a photo of the holotype from the American Museum of Natural History and developed doubts due to its apparent flat flank.

Update June 2023. I recovered a ventrolateral shoulder node from the original site. This will undoubtedly help sway its family assignment.

The following specimen is assignable to Mahoningoceras Murphy 1974, yet there are problems. Among the most compelling reasons to assign it to this genus are its open umbilicus, convex venter sutures, and general size. This contrasts with the known specimens of Millkoninckioceras, which have straight sutures and is rounded in cross-section throughout.

Over the Summer, several features have made me question Mahoningoceras. I requested a modern color photo of the holotype (FI 7425G) from the American Museum of Natural History and was surprised to see a specimen with flattened flanks. My specimen starts rounded in cross-section and transitions to a trapezoidal conch. It is also much larger than the holotype. It also has undetectable vertical striations.

This coiled nautiloid cephalopod immediately catches your eye because of its size. At its widest point, the conch diameter is 17 cm. No commonly collected coiled Pennsylvanian cephalopods reach such a large conch size. The larger the shell is in life, the more likely it will break down into smaller pieces after death. Another rare feature is the open umbilicus, whereas most coiled cephalopods found in rocks from the Pennsylvanian age have a closed umbilicus.

Family Placement

In a hierarchy list provided by Sturgeon et al. (1997), they place (pg. 2) Mahoningoceras under Temnocheilidae Mojsisovics 1902. Yet, in the remarks for the genus (pg. 55), they wrote: “The recognition of relationship with other temnocheilids places Mahoningoceras in the family Koninckioceratidae and not in the family Grypoceratidae as Murphy surmised.” I am unsure if this belongs in the Koninckioceratidae or the Temnocheilidae. The 1997 book had a 14-year delay before publication, and updates before going to press may have pushed portions of the content out of sync.

Mahoningoceras? sp.

Order: Nautilida

Superfamily: Tainocerataceae

Family: Tainoceratidae? Hyatt, 1900

Genus Mahoningoceras? Murphy 1974

Type Species—Nautilus (Gyroceras?) subquadrangularis Whitfield, 1882

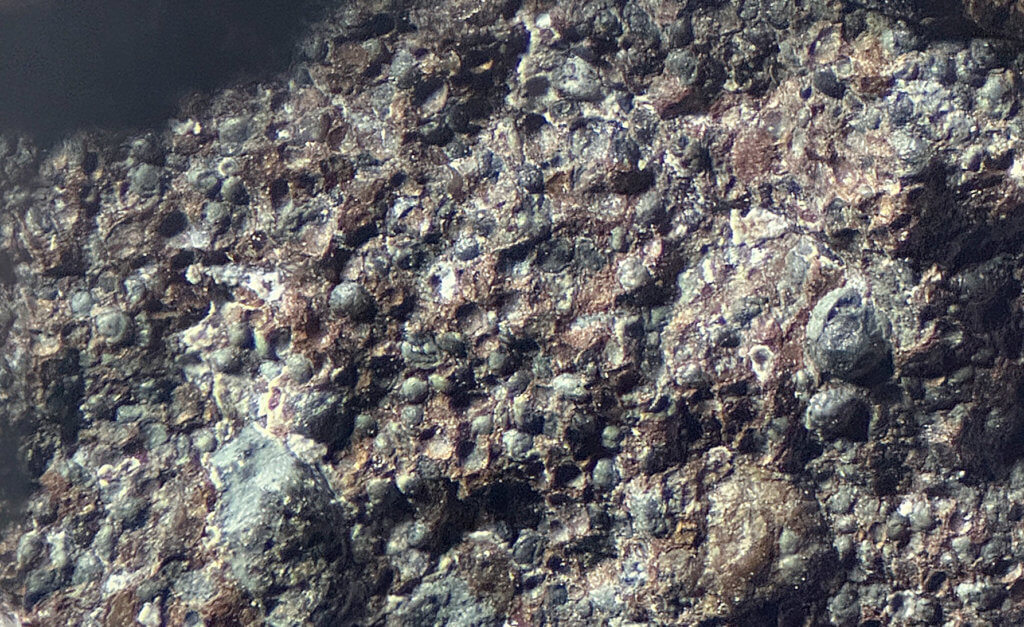

Remarks—Mahoningoceras is distinct, with an open umbilicus, an area that is often closed in nautiloids from the Pennsylvanian period. Its growth is consistent, with each chamber expanding slowly. The specimen consists of 2 and 1/4 whorls of the phragmocone; the body chamber length is supposed to be another one-quarter whorl. The first complete whorl appears circular in cross-section, transitioning to a subquadrangular shape in the final whorl. At least 40 camerae are observable, some obscured by the test or missing. Within the pieces that broke during recovery, some of the chambers continue toward their center, suggesting that many were unbroken after burial. The anterior end of the specimen appears to be the posterior margin of the body chamber, as the distance from the last suture is nearly double the previous one.

The fact that this creature had raised nodes was not apparent on the steinkern, but I later recovered a part of the shell with a large raised node. In a cross-section break, the node is infilled towards the body chamber, explaining the lack of node detail on steinkerns. The shell appears to be crushed. The sutures across the flank are straight.

Compared to AMNH 7425-G

The whorl shape between the two is very similar. The figure below shows the open umbilicus and even the number of preserved whorls is almost the same. The flank on 7425-G is flat, but CG-0650 appears crushed and splayed out. The tall umbilical feature may be seen head-on in 7425-G, thus creating confusion. Study of the two together would go a long way to clear things up.

Specimen Photos

Mahoningoceras subquadrangulare (Whitfield, 1882)

Mahoningoceras Murphy, 1974 is an enormous and rare coiled cephalopod from the Pennsylvanian period. Only three known specimens from the Pottsville Formation of Ohio and one from the Burgner Formation in Missouri are known. Sturgeon et al. (1997) determined the Missouri specimen—previously named Temnocheilus searighti Unklesbay & Palmer 1958—to be a juvenile example of Mahoningoceras due to its open umbilicus and longitudinal lines on the posterior shell.

The holotype of Mahoningoceras subquadrangulare (Whitfield, 1882) is deposited at the American Museum of Natural History under FI 7425G. I’ve requested modern photos of the holotype and will post them here if I get permission.

Field Report

A recent fossil hunting trip landed me in West Virginia at an exposure of Glenshaw Formation limestone. Heckel et al. (2011) determined this layer to be the Portersville Limestone, named the Woods Run limestone in Western Pennsylvania. The limestone—about a foot in thickness—has an upper fossil-rich layer with the gastropod Strobeus as the dominant fossil genus. This reddish layer appears iron-manganese rich and has a sandy consistency. Fossils brought back dried with a white haze that could be reduced with water washing. Parts of the limestone contain a matrix embedded with small pebbles, which can superficially look like the vascular canals in shark teeth.

The Portersville dark shale is exposed above the limestone, is thick, and I could find no apparent fossils in this layer.

References

- Heckel, P. H., Barrick, J. E., Rosscoe, S. J., 2011, Conodont-based correlation of marine units, lower Conemaugh Group, Appalachian Basin, stratigraphy, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 253–269, text-figures 1–4, plates 1–2, appendix 1, 2011

- deKoninick, L. G., 1878, Fauna du Calcaire Carbonifere de la Belgique; Premiere partie: Mus. Royale Hist. Nat. Belg. Ann., t. 2, pp. 1-152, pls. 1-31.

- Kummel, B., 1963, Miscellaneous nautilid type species of Alpheus Hyatt. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, 128 (6): 325–368.

- Miller, A. K., C. O. Dunbar, G. E. Condra, 1933, The nautiloid cephalopods of the Pennsylvanian system in the Mid-Continent region. Nebraska Geological Survey, 9 (2): 1–240.

- Miller, A. K., A. H. Kemp, 1947, A Koninckioceras from the Lower Permian of North-Central Texas. Journal of Paleontology, 21 (4): 351–354.

- Morningstar, H., 1922, Pottsville fauna of Ohio. Ohio Geological Survey, Bulletin 25, 312 pp.

- Murphy, J. L., 1974, R. P. Whitfield’s Nautiloid Species from the Pottsville Group of Ohio. Journal of Paleontology, 48(4), 740–749.

- Newell, N. D., 1936, Some Mid-Pennsylvanian Invertebrates from Kansas and Oklahoma: III. Cephalopoda. Journal of Paleontology, 10 (6): 481–489.

- Sturgeon, M. T., Windle, D. L., Mapes, R. H., Hoare, R. D., 1997, “Bulletin 71: Pennsylvanian Cephalopods of Ohio”, Part 1 Nautiloid and Bactritoid Cephalopods, Ohio Division of Geological Survey

- Unklesbay, A. G., & Palmer, E. J., 1958, Cephalopods from the Burgner Formation in Missouri. Journal of Paleontology, 32(6), 1071–1075.

- Whitfield, R. P. 1882. Descriptions of new species of fossils from Ohio, with remarks on some of the geological formations in which they occur. N.Y. Acad. Sci., Ann. 2:193-244.